Copernical Team

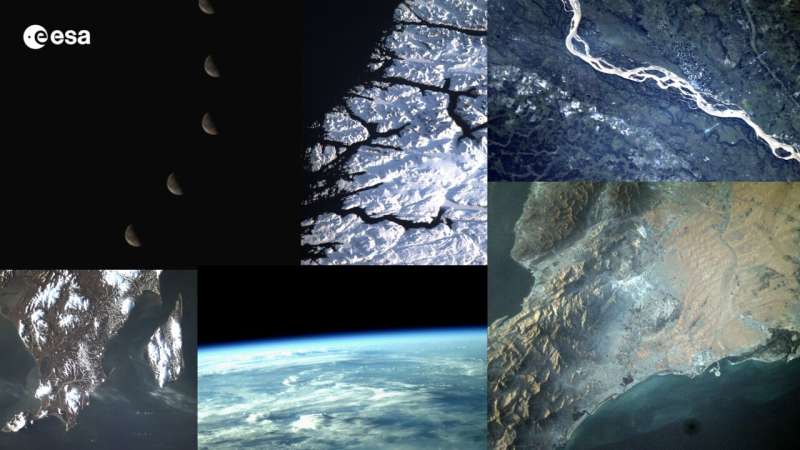

Mission complete for ESA's OPS-SAT flying laboratory

Launched on 18 December 2019, OPS-SAT was tasked with opening up the world of spacecraft operations to the widest possible audience. Its founding principle was to provide a fast, no-charge, non-bureaucratic experiment service for European and Canadian industry and academia.

It brought experimenters from companies, universities and public institutions across Europe and beyond into the heart of ESA's ESOC mission control center and helped them prove that their new ideas were up to the challenge of flying in orbit.

Flying ESA's most capable and flexible onboard computer, OPS-SAT showed us what future satellites will be capable of as they begin to carry more advanced equipment.

An in-orbit laboratory open to all

OPS-SAT was the first fully ESA-owned and operated CubeSat. A small, low-cost, innovative and open mission was unusual for ESA mission control, which typically flies Europe's largest and most complex spacecraft around Earth and across the solar system.

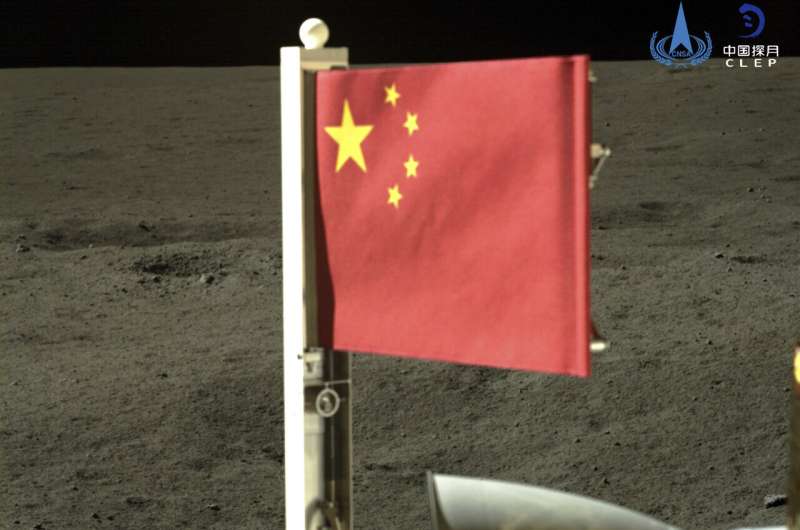

Craft unfurls China's flag on the far side of the moon and lifts off with lunar rocks to bring home

The Eagle-1 mission patch has landed

The Eagle-1 satellite team has revealed the design of their new mission patch. Originally associated with human spaceflight missions, patches are now released for a broad range of projects and expeditions. Here, we explore the development of an ESA mission patch, from concept to production.

Mission complete for ESA’s OPS-SAT flying laboratory

ESA’s experimental OPS-SAT CubeSat mission came to an end during the night of 22—23 May 2024 (CEST).

Prepare for the European Launcher Challenge

Electra's hybrid-electric aircraft achieves first ultra-short takeoff and landing

Electra.aero, Inc. (Electra), a next-gen aerospace company, announced it has successfully completed high-performance ultra-short flight operations of its piloted blown-lift hybrid-electric short takeoff and landing (eSTOL) demonstrator aircraft (EL-2 Goldfinch).

"Today's milestone is an incredible achievement as we've proven that our eSTOL aircraft has the capability to do what we said it

Electra.aero, Inc. (Electra), a next-gen aerospace company, announced it has successfully completed high-performance ultra-short flight operations of its piloted blown-lift hybrid-electric short takeoff and landing (eSTOL) demonstrator aircraft (EL-2 Goldfinch).

"Today's milestone is an incredible achievement as we've proven that our eSTOL aircraft has the capability to do what we said it Fresh water on Earth appeared 500 million years earlier than previously thought

New research led by Curtin University indicates that fresh water appeared on Earth about four billion years ago, which is 500 million years earlier than previously believed.

Dr. Hamed Gamaleldien, Adjunct Research Fellow at Curtin's School of Earth and Planetary Sciences and an Assistant Professor at Khalifa University, UAE, stated that by examining ancient crystals from the Jack Hills in

New research led by Curtin University indicates that fresh water appeared on Earth about four billion years ago, which is 500 million years earlier than previously believed.

Dr. Hamed Gamaleldien, Adjunct Research Fellow at Curtin's School of Earth and Planetary Sciences and an Assistant Professor at Khalifa University, UAE, stated that by examining ancient crystals from the Jack Hills in Airlines eye 'new frontier' of AI ahead of global summit

Airlines may not be replacing pilots with artificial intelligence anytime soon, but aviation industry experts say the new technology is already revolutionising the way they do business.

"Data and AI are fantastic levers for the aviation sector," said Julie Pozzi, the head of data science and AI at Air France-KLM, ahead of the 80th meeting of the International Air Transport Association (IATA)

Airlines may not be replacing pilots with artificial intelligence anytime soon, but aviation industry experts say the new technology is already revolutionising the way they do business.

"Data and AI are fantastic levers for the aviation sector," said Julie Pozzi, the head of data science and AI at Air France-KLM, ahead of the 80th meeting of the International Air Transport Association (IATA) Turning up the heat on next-generation semiconductors

The scorching surface of Venus, where temperatures can climb to 480 degrees Celsius (hot enough to melt lead), is an inhospitable place for humans and machines alike. One reason scientists have not yet been able to send a rover to the planet's surface is because silicon-based electronics can't operate in such extreme temperatures for an extended period of time.

For high-temperature applica

The scorching surface of Venus, where temperatures can climb to 480 degrees Celsius (hot enough to melt lead), is an inhospitable place for humans and machines alike. One reason scientists have not yet been able to send a rover to the planet's surface is because silicon-based electronics can't operate in such extreme temperatures for an extended period of time.

For high-temperature applica China lunar probe takes off from Moon carrying samples

A Chinese probe carrying samples from the far side of the Moon started its journey back to Earth on Tuesday, the country's space agency said - a world first and a major achievement for Beijing's space programme.

The ascender module of the Chang'e-6 probe "lifted off from lunar surface" and entered a preset orbit around the Moon, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) said.

It wa

A Chinese probe carrying samples from the far side of the Moon started its journey back to Earth on Tuesday, the country's space agency said - a world first and a major achievement for Beijing's space programme.

The ascender module of the Chang'e-6 probe "lifted off from lunar surface" and entered a preset orbit around the Moon, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) said.

It wa