Copernical Team

The first cells might have used temperature to divide

A simple mechanism could underlie the growth and self-replication of protocells-putative ancestors of modern living cells-suggests a study publishing September 3 in Biophysical Journal. Protocells are vesicles bounded by a membrane bilayer and are potentially similar to the first unicellular common ancestor (FUCA). On the basis of relatively simple mathematical principles, the proposed model sug

A simple mechanism could underlie the growth and self-replication of protocells-putative ancestors of modern living cells-suggests a study publishing September 3 in Biophysical Journal. Protocells are vesicles bounded by a membrane bilayer and are potentially similar to the first unicellular common ancestor (FUCA). On the basis of relatively simple mathematical principles, the proposed model sug Scientists are using new satellite tech to find glow-in-the-dark milky seas of maritime lore

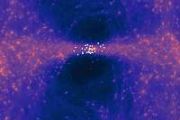

For centuries, sailors have been reporting strange encounters like the one above. These events are called milky seas. They are a rare nocturnal phenomenon in which the ocean's surface emits a steady bright glow. They can cover thousands of square miles and, thanks to the colorful accounts of 19th-century mariners like Capt. Kingman, milky seas are a well-known part of maritime folklore. But beca

For centuries, sailors have been reporting strange encounters like the one above. These events are called milky seas. They are a rare nocturnal phenomenon in which the ocean's surface emits a steady bright glow. They can cover thousands of square miles and, thanks to the colorful accounts of 19th-century mariners like Capt. Kingman, milky seas are a well-known part of maritime folklore. But beca AFRL offers university satellite program

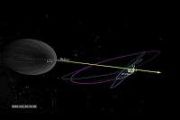

The Air Force Research Laboratory's University Nanosatellite Program (UNP) request for proposals (RFP) will be open until October 1. UNP funds U.S. university students and programs to design, build, launch, and operate small satellites with the primary goal to train the next generation of space professionals.

"For more than 20 years, UNP has equipped thousands of students across the countr

The Air Force Research Laboratory's University Nanosatellite Program (UNP) request for proposals (RFP) will be open until October 1. UNP funds U.S. university students and programs to design, build, launch, and operate small satellites with the primary goal to train the next generation of space professionals.

"For more than 20 years, UNP has equipped thousands of students across the countr ISRO developing microbe cultivation device for orbital biological experiments

According to state scientific representatives, India's space agency (ISRO) must identify indigenous solutions to achieve its ambitious space program. Researchers also state that the device has separate compartments that can conduct different kinds of experiments.

Scientific representatives from one of India's premiere institutes, the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), partnering with the

According to state scientific representatives, India's space agency (ISRO) must identify indigenous solutions to achieve its ambitious space program. Researchers also state that the device has separate compartments that can conduct different kinds of experiments.

Scientific representatives from one of India's premiere institutes, the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), partnering with the Astronomers nail down the origins of rare loner dwarf galaxies

By definition, dwarf galaxies are small and dim, with just a fraction of the stars found in the Milky Way and other galaxies. There are, however, giants among the dwarfs: Ultra-diffuse galaxies, or UDGs, are dwarf systems that contain relatively few stars but are scattered over vast regions. Because they are so diffuse, these systems are difficult to detect, though most have been found tucked wi

By definition, dwarf galaxies are small and dim, with just a fraction of the stars found in the Milky Way and other galaxies. There are, however, giants among the dwarfs: Ultra-diffuse galaxies, or UDGs, are dwarf systems that contain relatively few stars but are scattered over vast regions. Because they are so diffuse, these systems are difficult to detect, though most have been found tucked wi Hubble discovers hydrogen-burning white dwarfs enjoying slow aging

Could dying stars hold the secret to looking younger? New evidence from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope suggests that white dwarf stars could continue to burn hydrogen in the final stages of their lives, causing them to appear more youthful than they actually are. This discovery could have consequences for how astronomers measure the ages of star clusters, which contain the oldest known stars in t

Could dying stars hold the secret to looking younger? New evidence from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope suggests that white dwarf stars could continue to burn hydrogen in the final stages of their lives, causing them to appear more youthful than they actually are. This discovery could have consequences for how astronomers measure the ages of star clusters, which contain the oldest known stars in t Astronomers explain origin of elusive ultradiffuse galaxies

As their name suggests, ultradiffuse galaxies, or UDGs, are dwarf galaxies whose stars are spread out over a vast region, resulting in extremely low surface brightness, making them very difficult to detect. Several questions about UDGs remain unanswered: How did these dwarfs end up so extended? Are their dark matter halos - the halos of invisible matter surrounding the galaxies - special?

As their name suggests, ultradiffuse galaxies, or UDGs, are dwarf galaxies whose stars are spread out over a vast region, resulting in extremely low surface brightness, making them very difficult to detect. Several questions about UDGs remain unanswered: How did these dwarfs end up so extended? Are their dark matter halos - the halos of invisible matter surrounding the galaxies - special? NASA confirms Perseverance Mars rover got its first piece of rock

NASA confirmed Monday that its Perseverance Mars rover succeeded in collecting its first rock sample for scientists to pore over when a future mission eventually brings it back to Earth.

"I've got it!" the space agency tweeted, alongside a photograph of a rock core slightly thicker than a pencil inside a sample tube.

The sample was collected on September 1, but NASA was initially unsure

NASA confirmed Monday that its Perseverance Mars rover succeeded in collecting its first rock sample for scientists to pore over when a future mission eventually brings it back to Earth.

"I've got it!" the space agency tweeted, alongside a photograph of a rock core slightly thicker than a pencil inside a sample tube.

The sample was collected on September 1, but NASA was initially unsure Protective equipment against radiation to be tested on Nauka Module on ISS in 2023

New equipment that will help protect people from radiation during interplanetary flights will be tested on the Russian Nauka multipurpose laboratory module at the International Space Station, the head of the nuclear planetology department at the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Igor Mitrofanov, said.

"We are wrapping up the construction of a design and developme

New equipment that will help protect people from radiation during interplanetary flights will be tested on the Russian Nauka multipurpose laboratory module at the International Space Station, the head of the nuclear planetology department at the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Igor Mitrofanov, said.

"We are wrapping up the construction of a design and developme NASA begins air taxi flight testing with Joby

NASA began flight testing Monday with Joby Aviation's all-electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft as part of the agency's Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) National Campaign. This testing runs through Friday, Sept.10, at Joby's Electric Flight Base located near Big Sur, California. This is the first time NASA will test an eVTOL aircraft as part of the campaign. In the future, eVTOL airc

NASA began flight testing Monday with Joby Aviation's all-electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft as part of the agency's Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) National Campaign. This testing runs through Friday, Sept.10, at Joby's Electric Flight Base located near Big Sur, California. This is the first time NASA will test an eVTOL aircraft as part of the campaign. In the future, eVTOL airc