The space sector can boost whole economies.

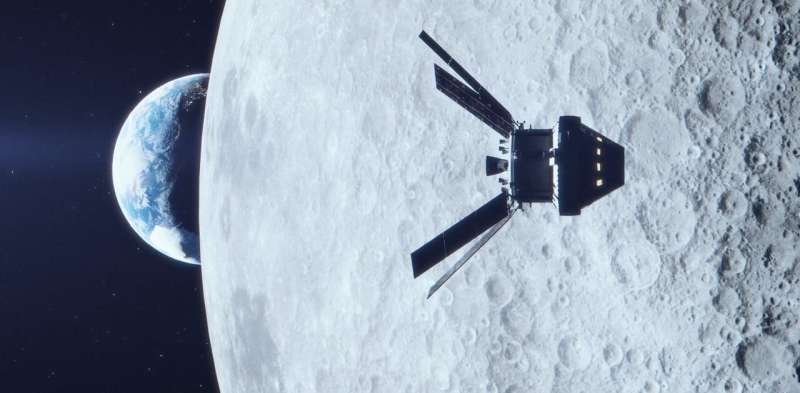

In the 1960s, the space race was driven mostly by Cold War-era political and military muscle flexing. There is still some of that in addition to the rush for resources. After 1972, human spaceflight became limited to low Earth orbit as the US switched from the Apollo spacecraft to the space shuttle. But in the 2000s, the US announced that it would be building new space vehicles to ferry astronauts to deep space destinations such as the moon.

Private pioneers

That same decade, the US also made a strategic decision to employ the ingenuity and cost effectiveness of young companies such as SpaceX and Blue Origin. Owned by some of the world's richest entrepreneurs—Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, respectively—they are marked on the outside by passion and risk-taking, but are based on solid business models.

SpaceX's enormous Starship vehicle was contracted by NASA to ferry Artemis astronauts between the proposed Gateway station orbiting the moon and the lunar surface. Starships were destroyed on each of their first three test flights. However, the pace at which problems are rectified is remarkable, and a year later, the fourth integrated test flight of Starship saw both the upper stage and Super Heavy rocket make soft landings.

This reaffirms SpaceX's competence in breaking frontiers of innovation and to provide reliable, affordable services. It is renowned for its upright return landings of launch vehicles—essential for human missions to and from the surfaces of the moon and Mars. However, Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin has been contracted to land the Artemis-5 crew on the moon later this decade, with its own lander. NASA clearly does not want to place all its eggs in one basket.

National and commercial ambitions

Recent attempts to land on the moon have highlighted the fine line between success and failure. A fuel leak cut short a mission by private company Astrobotic in January 2024. It was part of a NASA program aimed at kickstarting private transport services to the moon.

A thruster malfunction caused Russia's Luna 25 to crash during an attempt at a first landing near the lunar south in August 2023. This occurred as Russia appeared to be losing its front-row seat in scientific and commercial space activity. A few days later, India's Chandrayaan 3 lander touched down successfully, making India the fourth nation to softly land on the moon.

Japan followed suit in January 2024 when their Slim mission landed. Shortly afterwards, Houston-based Intuitive Machines later became the first private company to make a soft (if wonky) landing on the moon. Its Odysseus lander vindicated NASA's belief in private enterprise engagement as the future for sustained lunar exploitation.

Long-established aerospace companies such as Boeing are heavily involved in Artemis. But it seems just a matter of time until relatively new kids on the block can go it alone, without the burden of a space agency's bureaucracy and the whims of congressional approval.

China enters the fray

There are two other relevant players in the moon race. The China National Space Administration (CNSA)'s human space program has been catching up fast. Operating its own space station, Tiangong, it has replaced Russia as the main competitor to NASA.

China aims to place boots on the lunar soil by 2030 and build a base called the International Lunar Research Station. They will partner with Russia and various countries with little or no previous space experience, such as South Africa and Egypt. CNSA's lunar program has been flawless, with the uncrewed Chang'e 6 spacecraft landing softly on June 1, 2024. Its objective is to return samples of soil and rock from the far side of the moon.

The other player is the US Department of Defense. Its Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and Novel Orbital moon Manufacturing Materials and Mass efficient Design program is aimed at developing the capability to build things in space. Its Lunar Architecture study LunA-10, to be carried out over ten years, aims to develop infrastructure for the lunar economy such as transportation, wireless power generation and a communications grid.

But with this intense effort, come ethical questions and a need for enforceable laws and regulations. Is it right to mine the moon? Who owns the land there?

We also need to think about whether the water at the lunar south pole should be consumed until there is nothing left. Dating to 1967, the UN Outer Space Treaty stipulates peaceful activity in space and on other celestial bodies. But these are non-binding principles which say little about economic activity. Neither do the US Artemis Accords, which have been signed by 42 countries as of May 2024. These do not include China and Russia.

It is almost certain that by the mid-2030s there will be two lunar bases in operation. Private and state-owned companies will harness its resources, manufacture products, generate energy and offer stays for tourists.

All this comes with technological innovation that may provide solutions on Earth. The race to the moon offers opportunities for peaceful international cooperation and shared economic prosperity. It will also inspire a new generation of engineers and entrepreneurs. For better or for worse, it will be a milestone in the evolution of our species and bring Mars within reach as our next destination.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()