Astronomers have discovered black holes ranging from a few times the sun's mass to tens of billions. Now a group of scientists has predicted that NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope could find a class of "featherweight" black holes that has so far eluded detection.

Today, black holes form either when a massive star collapses or when heavy objects merge. However, scientists suspect that smaller "primordial" black holes, including some with masses similar to Earth's, could have formed in the first chaotic moments of the early universe.

"Detecting a population of Earth-mass primordial black holes would be an incredible step for both astronomy and particle physics because these objects can't be formed by any known physical process," said William DeRocco, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California Santa Cruz who led a study about how Roman could reveal them.

A paper describing the results has been published in the journal Physical Review D. "If we find them, it will shake up the field of theoretical physics."

Primordial black hole recipe

The smallest black holes that form nowadays are born when a massive star runs out of fuel. Its outward pressure wanes as nuclear fusion dies down, so inward gravitational pull wins the tug-of-war. The star contracts and may get so dense it becomes a black hole.

But there's a minimum mass required: at least eight times that of our sun. Lighter stars will either become white dwarfs or neutron stars.

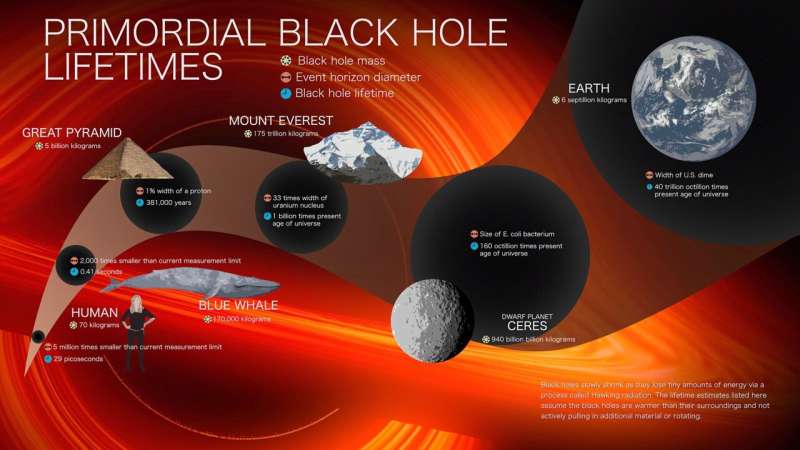

Conditions in the very early universe, however, may have allowed far lighter black holes to form. One weighing the mass of Earth would have an event horizon –– the point of no return for infalling objects –– about as wide as a U.S. dime coin.

Just as the universe was being born, scientists think it experienced a brief but intense phase known as inflation when space expanded faster than the speed of light. In these special conditions, areas that were denser than their surroundings may have collapsed to form low-mass primordial black holes.

While theory predicts the smallest ones should evaporate before the universe has reached its current age, those with masses similar to Earth could have survived.

Discovering these tiny objects would have an enormous impact on physics and astronomy.

"It would affect everything from galaxy formation to the universe's dark matter content to cosmic history," said Kailash Sahu, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, who was not involved in the study. "Confirming their identities will be hard work and astronomers will need a lot of convincing, but it would be well worth it."

Hints of hidden homesteaders

Observations have already revealed clues that such objects may be lurking in our galaxy. Primordial black holes would be invisible, but wrinkles in space-time have helped round up some possible suspects.

Microlensing is an observational effect that occurs because the presence of mass warps the fabric of space-time, like the imprint a bowling ball makes when set on a trampoline. Any time an intervening object appears to drift near a background star from our vantage point, the star's light must traverse the warped space-time around the object. If the alignment is especially close, the object can act like a natural lens, focusing and amplifying the background star's light.

Separate groups of astronomers using data from MOA (Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics) –– a collaboration that conducts microlensing observations using the Mount John University Observatory in New Zealand –– and OGLE (the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment) have found an unexpectedly large population of isolated Earth-mass objects.

Planet formation and evolution theories predict certain masses and abundances of rogue planets ––worlds roaming the galaxy untethered to a star. The MOA and OGLE observations suggest there are more Earth-mass objects drifting through the galaxy than models predict.

"There's no way to tell between Earth-mass black holes and rogue planets on a case-by-case basis," DeRocco said. But scientists expect Roman to find 10 times as many objects in this mass range than ground-based telescopes. "Roman will be extremely powerful in differentiating between the two statistically."

DeRocco led an effort to determine how many rogue planets should be in that mass range, and how many primordial black holes Roman could discern among them.

Finding primordial black holes would reveal new information about the very early universe, and would strongly suggest that an early period of inflation did indeed occur. It could also explain a small percentage of the mysterious dark matter scientists say makes up the bulk of our universe's mass, but have so far been unable to identify.

"This is an exciting example of something extra scientists could do with data Roman is already going to get as it searches for planets," Sahu said. "And the results are interesting whether or not scientists find evidence that Earth-mass black holes exist. It would strengthen our understanding of the universe in either case."

More information: William DeRocco et al, Revealing terrestrial-mass primordial black holes with the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, Physical Review D (2024). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevD.109.023013. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2311.00751

Journal information:Physical Review D, arXiv

Provided by NASA