Elon Musk's SpaceX achieved the feat with its Dragon capsule in 2020, ending a nearly decade-long dependence on Russian rockets following the end of the Space Shuttle program.

Astronauts Barry "Butch" Wilmore and Sunita "Suni" Williams were strapped into their seats preparing for liftoff when the call for a "scrub" came, because engineers heard buzzing from a valve that regulates liquid oxygen pressure on the Atlas V rocket meant to propel Starliner into orbit.

Tory Bruno, president and CEO of United Launch Alliance (ULA), which built the rocket, told reporters at a briefing the unusual vibrations detected from the valve could cause it to wear down, but he insisted "the crew was never in any danger."

When the next launch happens will now depend on the valve's condition and whether the rocket needs to be wheeled back to its hangar to install a replacement part.

"The team needs additional time to complete a full assessment, so we are targeting the next launch attempt no earlier than Friday, May 10," ULA, a Boeing-Lockheed Martin joint venture, said in a statement.

"We're taking it one step at a time and we're going to launch when we're ready, and fly when it's safe to do so," NASA's Steve Stich added.

History of setbacks

Following the decision to abort the launch, the astronauts, clad in blue spacesuits, were helped out of Starliner then boarded a van back to their quarters.

Wilmore and Williams, both Navy-trained pilots and space program veterans, have each been to the ISS twice, traveling once on a shuttle and then aboard a Russian Soyuz vessel.

Their new mission will see them put Starliner through its paces, piloting the craft manually to test its capabilities.

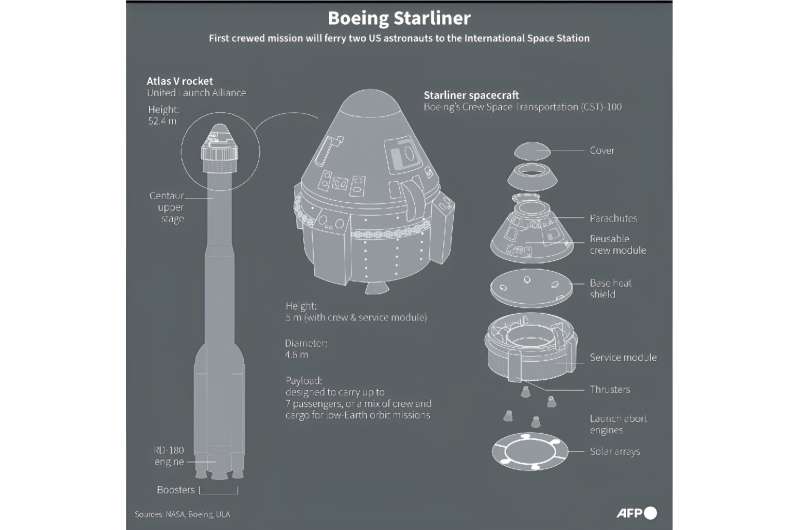

The gumdrop-shaped capsule with a cabin about as roomy as an SUV is set to rendezvous with the space station for a weeklong stay, before returning to Earth for a parachute-assisted landing in the western United States.

A successful mission would help dispel the bitter taste left by numerous setbacks in the Starliner program.

In 2019, during a first uncrewed test flight, two separate software defects meant the capsule was not placed on the right trajectory and returned without reaching the ISS, and could have suffered collision between its modules.

"Ground intervention prevented loss of vehicle," said NASA in the aftermath, chiding Boeing for inadequate safety checks.

Then in 2021, with the rocket on the launchpad for a new flight, blocked valves forced another postponement.

The vessel finally reached the ISS in May 2022 in a non-crewed launch. But other problems that came to light—including weak parachutes and flammable tape in the cabin that needed to be removed—caused further delays to the crewed test flight.

Exclusive club

SpaceX meanwhile has pulled ahead, carrying dozens of astronauts into orbit on missions for NASA and private clients.

In 2014, NASA awarded fixed-price contracts of $4.2 billion to Boeing and $2.6 billion to SpaceX to develop the capsules under its Commercial Crew Program, marking a shift in approach from owning space flight hardware to instead paying private partners for their services as the primary customer.

Once Starliner is fully operational, the agency hopes to alternate between the two spaceships for taxi rides to the ISS.

Even though the research lab is due to be mothballed in 2030, both Starliner and Dragon could be used for future private space stations that several companies are developing.

© 2024 AFP