That's where the Department of Energy Office of Science's user facility supercomputers come in. Researchers at DOE's Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility (OLCF) are working with NASA engineers and scientists to simulate the process of slowing down a huge spacecraft as it moves towards Mars' surface.

Landing spacecraft on Mars isn't new to NASA. The agency ran its first missions to the planet in 1976 with the Viking project. Since then, NASA has successfully carried out eight additional Mars landings.

What makes this goal different is the fact that it's much more difficult to land the huge spacecraft required for human exploration than those for robotic missions. The robotic vehicles use parachutes to decelerate through Mars' atmosphere. But a spacecraft carrying humans will be about 20 to 50 times heavier.

A vehicle this large simply can't use parachutes. Instead, NASA will need to rely on retro-propulsion. This technology uses rockets that fire forward to slow down the vehicle as it approaches the surface.

A number of challenges come with using retro propulsion. The high-energy rocket engine exhaust interacts with both the vehicle and the Martian atmosphere. Those dynamics change how the team needs to guide and control the vehicle. In addition, engineers can't fully replicate how a flight on Mars would go on Earth. While they can test spacecraft in wind tunnels and use other tools, those tools aren't a perfect replacement or direct analog for the Martian environment.

To fill in the gaps, NASA turned to the OLCF supercomputers and their expert computer scientists. In theory, programs running on supercomputers could fully simulate the Martian environment and many of the complex physics associated with using retropropulsion.

The project team has relied on FUN3D, a long-standing suite of software tools that models how fluids—including air—move. Engineers created the first version of the code in the late 1980s and have continually made major improvements since then. Agencies and companies in aeronautics and space technology have used it to tackle major challenges.

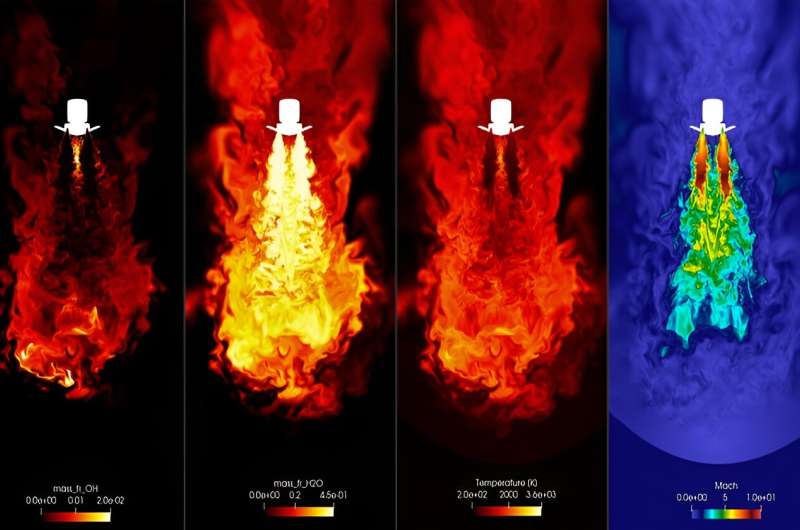

The current Mars effort began in 2019 on Summit, OLCF's fastest computer at the time. The initial simulations assumed fixed conditions. They simulated just one point along the vehicle's trajectory. Those early versions allowed scientists to evaluate the impacts of flight speeds, engine settings, and more. Further developments enabled engineers to explore real gas effects.

They could account for the liquid oxygen-methane rocket engines and the carbon dioxide-heavy Martian atmosphere. Even these early simulations typically resulted in petabyte-sized datasets. It would take about 1,000 powerful home computers to store a single petabyte. But even these weren't full simulations—that wasn't possible yet.

The next step was to incorporate a whole new piece of software into the simulation—the Program to Optimize Simulated Trajectories (POST2). NASA developed POST2 to analyze flight mechanics for a broad range of applications. While initial simulations relied on static conditions, POST2 allowed scientists to dynamically "fly" the vehicle in the simulation. The team engaged researchers from Georgia Tech's Aerospace Systems Design Laboratory.

They had previously developed unique strategies to couple POST2 with high-fidelity aerodynamic simulations. Incorporating POST2 also required engineers to change the project workflow. The software's use was restricted to NASA computing systems for security reasons. As such, the team needed to ensure the NASA systems could communicate smoothly with Summit at OLCF.

Resolving issues with firewalls, network interruptions, and other programs required a full year of planning for the cybersecurity and system administration teams at both facilities!

The latest advance involved moving the entire simulation over to the newest and most powerful computer at OLCF—Frontier. The first exascale computer in the world, Frontier is massively more powerful than previous supercomputers. With a series of coordinated runs over a two-week period, the team ran its most elaborate flight simulation to date.

It was a 35-second closed-loop descent from 5 miles altitude to approximately 0.6 miles. The simulation slowed the vehicle from 1,200 miles per hour to approximately 450 miles per hour. POST2 was able to autonomously control the vehicle in a stable fashion using its eight main engines and four reaction control system modules.

With the immense power provided by Frontier at OLCF, NASA engineers are moving forward to tackle new frontiers in space travel.

Provided by US Department of Energy