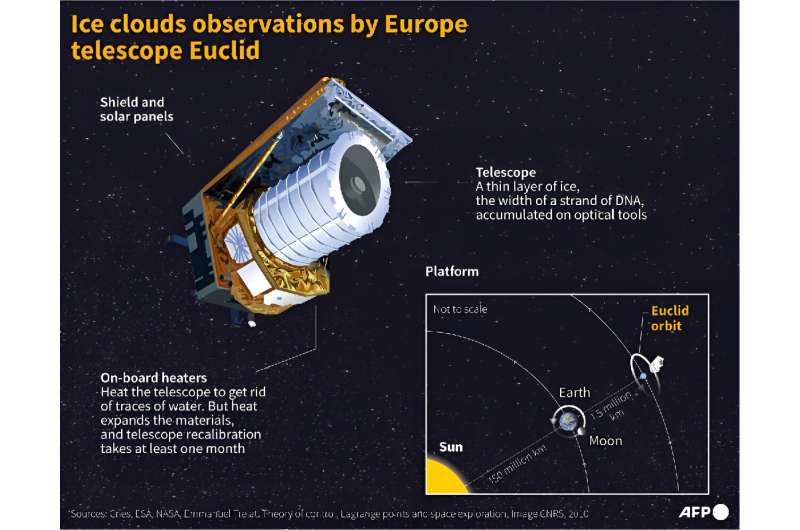

There are heaters onboard that can warm up the entire spacecraft, a process that was carried out shortly after Euclid launched.

But heat expands many materials, and warming up the whole spacecraft now would require careful recalibration.

That had the potential to delay the telescope's mission by months, Euclid instrument operations scientist Ralf Kohley told AFP last week.

So the team opted instead to warm up single mirrors, hoping to clear up the problem without having to heat the whole spacecraft.

Kohley had said they would move through a number of different mirrors until they found the right one.

But the ESA emphasized they had solved the problem by heating up the very first mirror attempted.

Wide view of the universe

Keeping out water is a common problem for all spacecraft.

Despite best efforts on the ground, a tiny amount of water absorbed during a spacecraft's assembly on Earth can smuggle its way to space.

Faced with the cold vastness of space, the water molecules freeze to the first surface they can—in this case Euclid's mirrors.

The ice was not Euclid's first setback.

The team on the ground previously fixed a software problem in which cosmic rays confused the spacecraft's guidance sensor.

Some unwanted sunlight also interfered with the telescope's observations, a problem solved by slightly rotating the spacecraft, Kohley said.

Euclid is not far from its fellow telescope, the James Webb, at a stable hovering spot around 1.5 million kilometers (more than 930,000 miles) from Earth.

In contrast to Webb's spectacularly long-distance sight, Euclid takes in a far wider view of the cosmos.

It will use this vision to chart one third of the sky—encompassing a mind-boggling two billion galaxies—to create what has been billed as the most accurate 3D map ever of the universe.

Scientists hope this will help shed more light on dark matter and dark energy, which are thought to make up 95 percent of the universe but remain shrouded in mystery.

© 2024 AFP