They increasingly help NASA scientists and explorers navigate, map, and collect scientific data.

Engineers and scientists at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, continue to refine lidars into smaller, lighter, more versatile tools for science and exploration, with help from hardware provided by small business and academic partners.

"Existing 3D-imaging lidars struggle to provide the 2-inch resolution needed by guidance, navigation and control technologies to ensure precise and safe landings essential for future robotic and human exploration missions," team engineer Jeffrey Chen said. "Such a system requires 3D hazard-detection lidar and a navigation doppler lidar, and no existing system can perform both functions."

Enter CASALS, the Concurrent Artificially intelligent Spectrometry and Adaptive Lidar System. Developed through Goddard's IRAD, Internal Research and Development program, CASALS shines a tunable laser through a prism-like grating to spread the beam based on its changing wavelengths. Traditional lidars pulse a fixed-wavelength laser which is split into multiple beams by bulky mirrors and lenses to split it into multiple beams. One CASALS instrument could cover more of a planet's surface in each pass than lidars used for decades to measure Earth, the moon, and Mars.

CASALS's smaller size, weight, and lower power requirements enable small satellite applications as well as handheld or portable lidars for use on the moon's surface, Goddard engineer and CASALS development lead Guangning Yang said.

The CASALS team received funding from NASA's Earth Science Technology Office to test their improvements by airplane in 2024, bringing their system closer to spaceflight readiness.

What color is your lidar?

As lidars become more specialized, CASALS can incorporate different wavelengths, or colors of laser light for applications like Earth science, exploring other planets and objects in space, and navigation and rendezvous operations.

The CASALS Team used Goddard IRAD and NASA SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research Program) funding along with commercial partners Axsun Technologies and Freedom Photonics to develop new fast-tuning lasers in the 1-micron portion of the infrared spectrum for Earth science and planetary exploration. By comparison, commonly available lidars used for self-driving vehicle development typically use 1.5-micron lasers for range and speed calculations.

On Earth, wavelengths near 1 micron pass readily through the atmosphere and are good at differentiating vegetation from bare ground, said Ian Adams, Goddard's chief technologist for Earth sciences. Wavelengths near 0.97 and 1.45 microns offer valuable information about water vapor in Earth's atmosphere but do not travel as efficiently to the surface.

In a related project, the team partnered with Left Hand Design Corporation to develop a steering mirror to extend CASALS's 3D-imaging coverage and improve resolution. He said the lidar's higher pulse rate can build up signal sensitivity to provide range and velocity measurements at up to 60 miles.

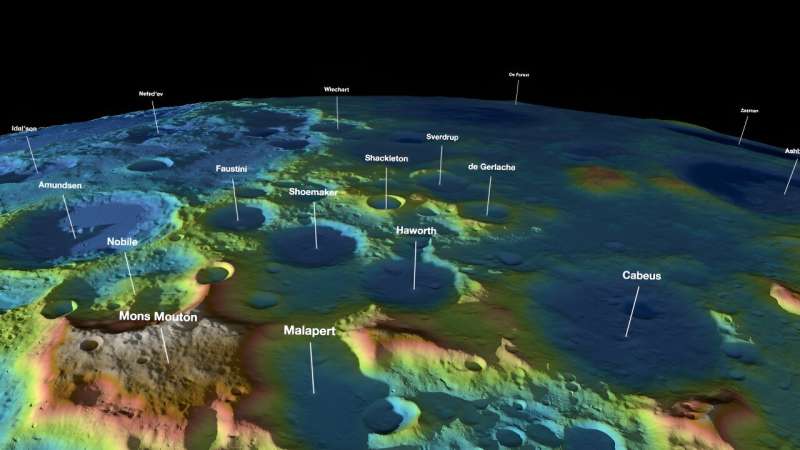

Artemis-related missions seeking to land near the moon's South Pole could also use CASALS's sharper imaging to help assess the safety of potential landing sites.

Bringing the moon into focus

More detailed 3D models of the moon drove Goddard planetary scientist Erwan Mazarico's IRAD effort to refine CASALS's ability to measure surface details smaller than 3 feet. He said this will help understand the moon's sub-surface structures and changes over time.

Every month, Earth's path across the lunar sky moves within 10 or 20 degrees of the center of the side facing Earth.

"We've predicted based on our understanding of its inner structure that Earth's shifting pull could change the tidal bulge or shape of the moon," Mazarico said. "High-resolution measurements of that deformation could tell us more about potential variations within the moon. Is it responding like a fully uniform body in the interior?"

NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) has measured Earth's natural satellite since 2009, modeling the moon's terrain and providing a wealth of discoveries with the help of LOLA, its Lunar Orbiting Lidar Altimeter. LOLA fires 28 laser pulses per second, split into five beams touching the surface 65 feet to 100 feet apart. Scientists use LRO images to estimate smaller surface features between laser measurements.

CASALS's laser, however, allows the equivalent of several hundred thousand pulses per second, reducing the distance between surface measurements.

"A denser and more accurate data set would allow us to study much smaller features," Mazarico said, including those from impacts, volcanic activity, and tectonics. "We're talking orders of magnitude more measurements. That could be quite a big game changer in terms of the type of data we get from lidar."

Provided by NASA