Previous technosignature surveys have included only the radio frequency band above 600 MHz, leaving lower frequencies virtually unexplored. That's despite the fact that everyday communication services such as air traffic control, marine emergency broadcasting and FM radio stations all emit this type of low-frequency radiation on Earth.

The reason it hasn't been explored is that telescopes that operate at these frequencies are rather new. And lower-frequency radio waves have less energy, meaning they can be more challenging to detect.

In our concluded survey, we ventured into these frequencies for the first time ever.

The Low Frequency Array (Lofar) is the world's most sensitive low-frequency telescope, operating from 10-250 MHz. It's composed of 52 radio telescopes with more on the way, spread across Europe. These telescopes can reach a high resolution when used in unison.

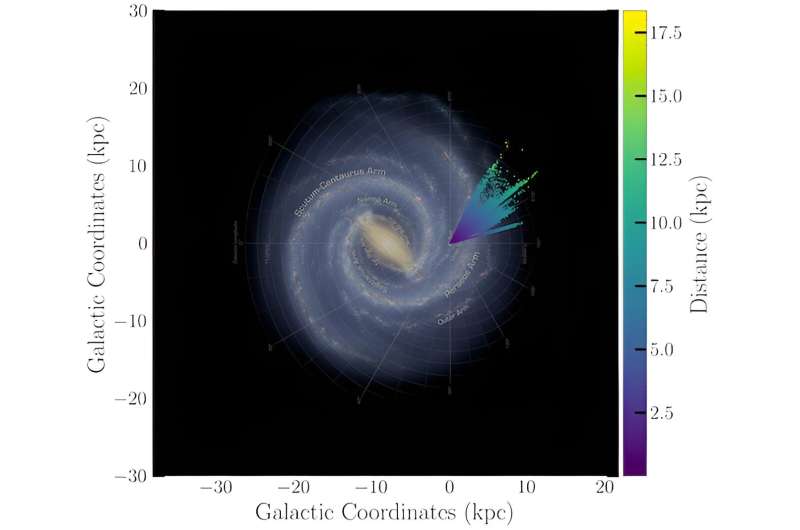

Our survey, however, only made use of two of these stations: one situated in Birr, Ireland, and the other in Onsala, Sweden. We surveyed 44 planets orbiting other stars than our sun that had been identified by NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite. Over the course of two summers, we scanned these planets at 110 to 190 MHz with our two telescopes.

Initially, this doesn't seem like a large amount of targets, but low-frequency observation boasts a major advantage in having large fields of view compared with their higher-frequency siblings. That's because the area of the sky covered decreases with higher frequencies.

In the case of Lofar, we covered 5.27 square degrees of the sky for each pointing of our telescopes. This culminated in 36,000 targets per telecope pointing—or more than 1,600,000 targets in total, when you check what other stars are nearby and include their planets as well.

Interfering signals

Searching for technosignatures from space introduces a significant challenge—the same technosignatures are ubiquitous on Earth. This presents an obstacle as the telescopes in these searches boast sensitivity levels that can detect signals, such as a phone call, from halfway across the solar system.

Consequently, the data collected is inundated with thousands of signals originating from Earth, posing a considerable difficulty in isolating and identifying signals that could be of extraterrestrial origin. The need to sift through this extensive and noisy dataset adds a layer of complexity to the search.

We came up with an innovative approach to mitigating such radio frequency interference, called the "coincidence rejection" method. This takes into account the local radio emissions at each of our telescopes. For example, if I am using the telephone close to the telescope in Ireland to call my supervisor, that same call won't appear in the data in Sweden, and vice versa (mainly because the telescope isn't pointing in our direction, it's pointing at an exoplanet candidate).

So, we decided to only include signatures in the dataset if they exhibited a simultaneous presence at both stations, suggesting they come from outside Earth.

In this way, we whittled down thousands of candidate signals to zero. This means we didn't find any signs of intelligent life with our search, but we have only just started—and there are likely to be an enormous number of Earth-like planets out there. Knowing that the coincidence rejection method works with a high success rate may be key to helping us discover life at one of these planets in the future.

There are many ways forward for technosignature searches at low frequencies. Currently, there is a sister survey (Nenufar) being carried out on that operates at 30-85 MHz. Along with this, further Lofar observations will increase the volume of the survey by a factor of ten over the course of the coming year. The collected data is also used for investigating astronomical objects known as pulsars, fast radio bursts, radio exoplanets and more.

Thankfully, we're only at the start of a long journey. I have no doubt that many wondrous things will be found. And if we're lucky, we may reap the biggest reward of all: some company in the cosmos.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()