Soon afterward there were some examples of using the effect to generate electric power, but the first true solar cells didn't appear until the mid-1900s.

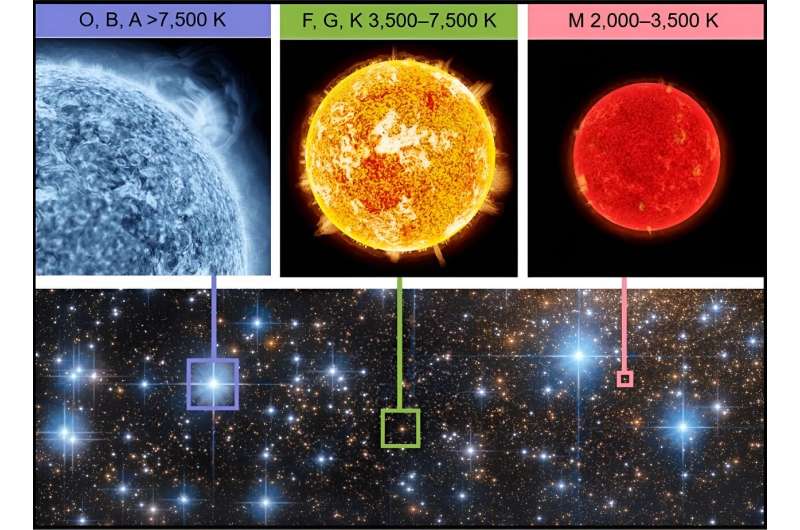

Since then research has focused on making solar cells lighter, cheaper, and more efficient. Modern solar panels can harness not just ultraviolet light, but also visible and in some cases infrared. But all of these designs are built to harness the sun, which gives off most of its light in the green range and emits plenty of ultraviolet light. But most exoplanets orbit red dwarf stars, which have a peak brightness in the red or infrared and emit little ultraviolet.

If we want to visit nearby planetary systems, such as the Proxima Centauri system, then we'll need to have solar panels capable of harnessing red dwarf starlight.

That's the topic of a recent study in Scientific Reports. The authors look at the efficiency of solar panels under a range of stellar spectra, particularly comparing the sun and Proxima Centauri. Their study focuses on organic photovoltaics (OPVs), which are both light and flexible. This would allow solar panels to be applied to large solar sails, which is a common design element for early interstellar probes.

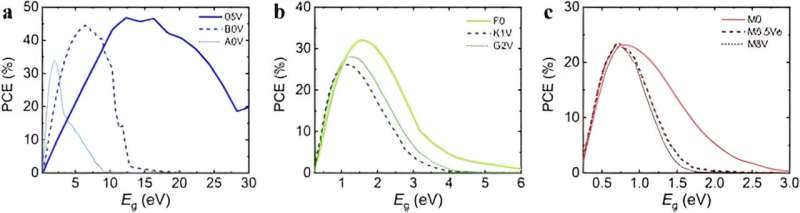

OPVs are a young technology, but they have an advantage over more established silicon-based cells in that they can be tuned to different wavelengths. The efficiency of a solar cell and the wavelengths from which it derives the most energy are based on what is known as the band gap.

Essentially, electrons bound to the cell material must capture enough energy from photons to jump across the band gap into the conduction band, where they can then flow as electric current. Using different organic materials, we can adjust the band gap to best suit the light available.

The team found that while a wider band gap works well for sunlight, the light of Proxima Centauri would require a narrow band gap. For example, a simulated wide band gap solar cell has a theoretical efficiency of 18.9% for sunlight, but only 0.9% for Proxima Centauri. In contrast, a narrow band gap model has a theoretical efficiency of 12.6% for Proxima Centauri.

So solar panels could generate electricity from red dwarf stars. But one major disadvantage remains. Since red dwarfs produce much less light than the sun, even with a good efficiency individual solar cells wouldn't produce nearly the amount of energy we can gather from the sun.

Interstellar solar panels would need to be significantly larger, which would greatly increase their weight and cost. But it is possible, and further materials research may find even more efficient methods of generating electricity from light.

More information: Nora Schopp et al, Interstellar photovoltaics, Scientific Reports (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-023-43224-5

Journal information:Scientific Reports

Provided by Universe Today