"With TIGERISS, the Pioneers expand their reach to the space station, which offers a unique platform for exploring the universe."

Eye of the TIGER

TIGERISS Principal Investigator Brian Rauch, research associate professor of physics at Washington University in St. Louis, has been working on questions of elemental origins and high-energy particles since he was an undergraduate there. For nearly three years in college, Rauch worked on a particle detector called Trans-Iron Galactic Element Recorder, or TIGER. The experiment had its first flight on a balloon in 1995; long-duration balloon flights also launched a version of TIGER from Antarctica in 2001 to 2002 and 2003 to 2004.

As Rauch progressed in his research career, he helped TIGER evolve into the more sophisticated SuperTIGER. On Dec. 8, 2012, SuperTIGER launched from Antarctica on its first flight, cruising at an average altitude of 125,000 feet and setting a new record for longest scientific balloon flight—55 days. SuperTIGER also flew for 32 days from December 2019 to January 2020. The experiment measured the abundance of elements on the periodic table up to barium, atomic number 56.

On the International Space Station, the TIGER instrument family will soar to new heights. Without the interference from Earth's atmosphere, the TIGERISS experiment will make higher-resolution measurements and pick up heavy particles that wouldn't be possible from a scientific balloon. A perch on the space station will also allow for a larger physical experiment—3.2 feet (1 meter) on a side—than could fit on a small satellite, increasing the potential size of the detector. And the experiment could last more than a year, compared to less than two months on a balloon flight. Researchers plan to be able to measure individual elements as heavy as lead, atomic number 82.

Star stuff

All stars exist in a delicate balance—they need to put out enough energy to counteract their own gravity. That energy comes from fusing elements together to make heavier ones, including carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen, which are important for life as we know it. But once a giant star tries to fuse iron atoms, the reaction doesn't generate enough power to fight gravity, and the star's core collapses.

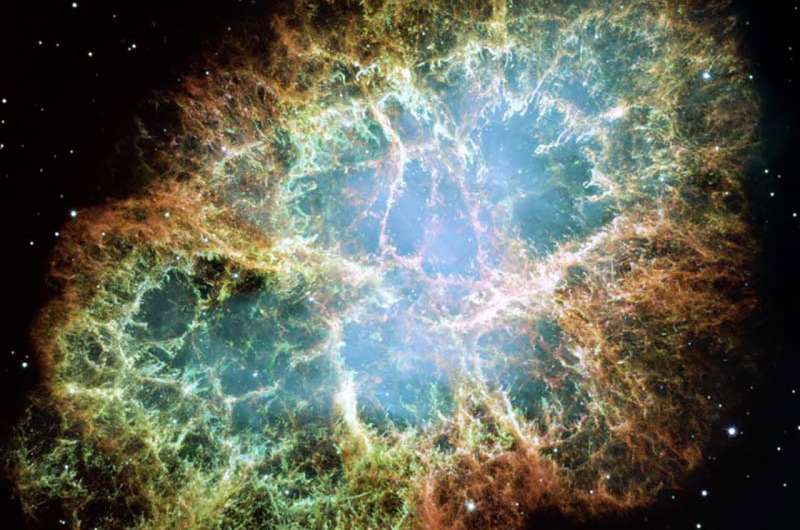

This triggers an explosion known as a supernova, in which shock waves cast out all of those heavy elements that had been made in the star's core. The explosion itself also creates heavy elements and accelerates them to nearly the speed of light—particles that scientists dub "cosmic rays."

But that's not the only way heavy atoms can form. When a superdense remnant of a supernova called a neutron star collides with another neutron star, their cataclysmic merger also creates heavy elements.

TIGERISS won't be able to point out particular supernovae or neutron star collisions, but "would add context as to how these fast-moving elements are accelerated and travel through the galaxy," Rauch said.

So how much do supernovae and neutron star mergers each contribute to making heavy elements? "That is the most interesting question we can hope to address," Rauch said.

"TIGERISS measurements are key to understanding how our galaxy creates and distributes matter," said John Krizmanic, TIGERISS's deputy principal investigator based at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

TIGERISS will also contribute information on the general abundance of cosmic rays, which pose a hazard to astronauts.

Explore further