The lander was projected to automatically shut down the seismometer—InSight's last operational science instrument—by the end of June in order to conserve energy, surviving on what power its dust-laden solar panels can generate until around December.

Instead, the team now plans to program the lander so that the seismometer can operate longer, perhaps until the end of August or into early September. Doing so will discharge the lander's batteries sooner and cause the spacecraft to run out of power at that time as well, but it might enable the seismometer to detect additional marsquakes.

"InSight hasn't finished teaching us about Mars yet," said Lori Glaze, director of NASA's Planetary Science Division in Washington. "We're going to get every last bit of science we can before the lander concludes operations."

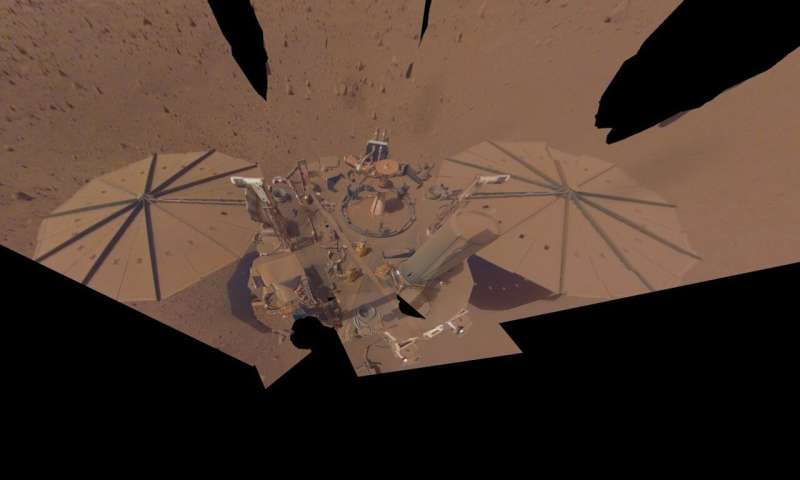

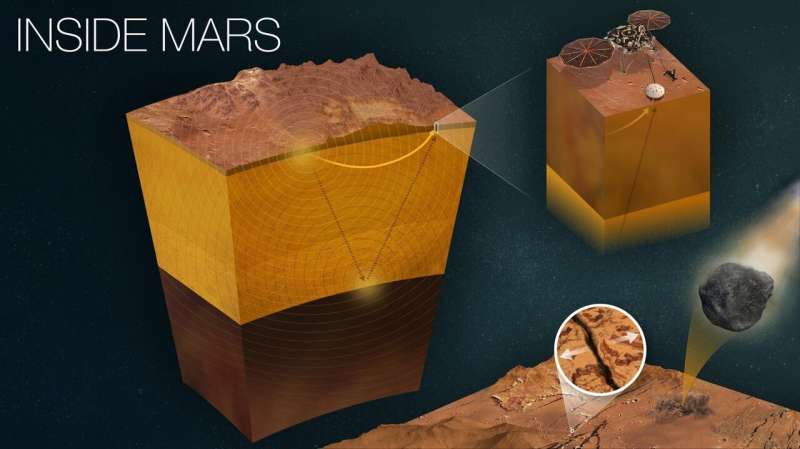

InSight (short for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport) is in an extended mission after achieving its science goals. The lander has detected more than 1,300 marsquakes since touching down on Mars in 2018, providing information that has allowed scientists to measure the depth and composition of Mars' crust, mantle, and core. With its other instruments, InSight has recorded invaluable weather data, investigated the soil beneath the lander, and studied remnants of Mars' ancient magnetic field.

All instruments but the seismometer have already been powered down. Like other Mars spacecraft, InSight has a fault protection system that automatically triggers "safe mode" in threatening situations and shuts down all but its most essential functions, allowing engineers to assess the situation. Low power and temperatures that drift outside predetermined limits can both trigger safe mode.

To enable the seismometer to continue to run for as long as possible, the mission team is turning off InSight's fault protection system. While this will enable the instrument to operate longer, it leaves the lander unprotected from sudden, unexpected events that ground controllers wouldn't have time to respond to.

"The goal is to get scientific data all the way to the point where InSight can't operate at all, rather than conserve energy and operate the lander with no science benefit," said Chuck Scott, InSight's project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.