Elena D'Onghia, an associate professor at the University of Wisconson–Madison's Department of Astronomy, and the principal investigator for CREW HaT. "We use new superconductive tape technology, a deployable design, and a new configuration for a magnetic field that hasn't been explored before."

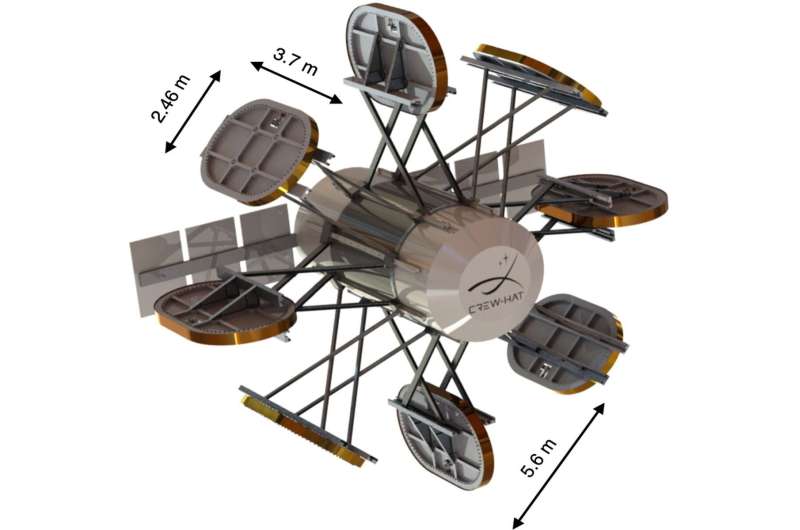

HaT stands for a Halbach Torus, which is a circular array of magnets that creates a stronger field on one side while reducing the field on the other side. D'Onghia and collaborator Paolo Desiati from the Wisconsin Icecube Particle Astrophysics Center (WIPAC) have come up with a design for lightweight, deployable, mechanically supported magnetic coils activated by a new generation of high-temperature superconducting tapes, which have only recently become available.

"This configuration produces an enhanced external magnetic field that diverts cosmic radiation particles, complemented by a suppressed magnetic field in the astronaut's habitat," the team wrote in their NIAC abstract.

"The geometry we propose creates a magnetic field outside the spacecraft but not inside, so the astronauts are not exposed," D'Onghia told Universe Today. "Previous proposals had the magnetic field quite close to the spacecraft and this would cause issues because magnetic fields can generate showers of secondary particles, like neutrons, that can be harmful to astronauts. Our concept suggests an open magnetic field that extends out into space."

D'Onghia said their new configuration produces an enhanced external magnetic field that diverts cosmic radiation particles, complemented by a suppressed magnetic field in the astronaut's habitat. The team believes their design can divert over 50% of the biology-damaging cosmic rays (protons below 1 GeV) and higher energy high-Z ions. This rate would be sufficient in reducing the radiation dose absorbed by astronauts to a level that is less than 5% of the lifetime excess risk of cancer mortality levels established by NASA.

There are two types of radiation that cause problems for long-duration human spaceflight. One is solar energetic protons, which come in bursts following a solar flare event. The second are galactic cosmic rays, which, although not as lethal as solar flares, would be a continuous background radiation to which the crew would be exposed. In an unshielded spacecraft, both types of radiation would result in significant health problems, or death, to the crew.

On Earth, our planet's magnetic field deflects cosmic rays, and an added measure of protection comes from our atmosphere which absorbs any cosmic radiation that makes its way through the magnetic field. The idea for magnetic shielding for spacecraft would be to have a spacecraft bring along a magnetic field equivalent to Earth's. But designing such shields that actually work and isn't prohibitively heavy has been a challenge.

The issue of radiation in space has long been known, and D'Onghia said there have been many, many ideas and proposals for creating shields for spacecraft, starting in the late 1960s and early 70s. But so far, nothing has been feasible or cost effective.

Universe Today has written about several previous ideas for shielding, including one that also received NIAC funding back in 2004. The concept was spearheaded by former astronaut Jeffrey Hoffman, however, the concept ultimately did not pan out, and Hoffman told me in 2006 that despite their theoretical calculations, they couldn't come up with a convincing design.

But that doesn't mean that the work of Hoffman's team wasn't important.

"Hoffman's concept has been popular for several years and is undoubtedly of interest and inspiration.," said D'Onghia said via email. "For example, we all agree that active shielding (e.g., an artificial magnetic field) must be combined with passive shielding (material that can absorb the radiation) to be more effective. The changing view in the last ten years is that we probably need a different magnetic field configuration compared to what was proposed previously."

When Hoffman's team was calculating their concept, superconductors were big, bulky and hard to build in space.

"There have been new generation superconductors (such as ReBCO, which we plan to use) in the last few years with a high critical temperature," D'Onghia said. "Those superconductors are very light (they look like a tape) and less expensive, and might be a real game-changer for this project."

Previous designs which included magnetic coils weighed as much as 300 tons for each coil. D'Onghia said their team plans to use eight coils, and they have been able to reduce the weight of their coils to 3 tons each. But they are still working on optimizing their design, which the grant from NIAC will allow them to do.

"We still need to reduce the weight and work on using new materials," D'Onghia said. "That is the big challenge, and we plan to keep working hard to figure this out."