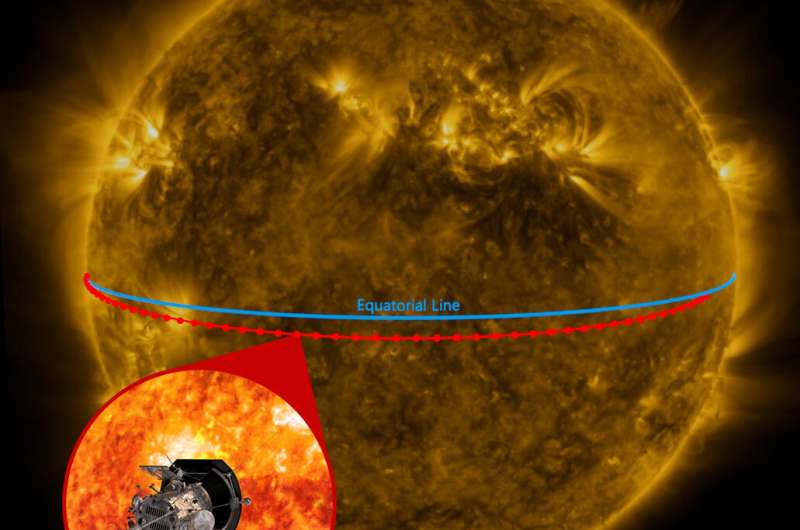

As NASA's Parker Solar Probe completes its latest swing around the sun, it's doing so in full view of dozens of other spacecraft and ground-based telescopes.

These powerful instruments can't actually see Parker itself—the van-sized spacecraft is far too small for visible detection—but they offer from a distance what the probe is sensing close-up, as it samples and analyzes the solar wind and magnetic fields from as close as 5.3 million miles (8.5 million kilometers) from the sun's surface.

Occurring at 10:36 a.m. EST (15:36 UTC) on Feb. 25, this was the 11th close approach—or perihelion in the spacecraft's orbit around the sun—of 24 planned for Parker Solar Probe's primary mission. Most of these passes occur while the sun is between the spacecraft and Earth, blocking any direct lines of sight from home. But every few orbits, the dynamics work out to put the spacecraft in Earth's view—and the Parker mission team seizes these opportunities to organize broad observation campaigns that not only include telescopes on Earth, but several spacecraft as well.

More than 40 observatories around the globe, including the recently commissioned Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii, among other major installations in the southwestern United States, Europe and Asia, are training their visible, infrared and radio telescopes on the sun over the several weeks around the perihelion. About a dozen spacecraft, including NASA's STEREO, Solar Dynamics Observatory, TIMED and Magnetospheric Multiscale missions, ESA's and NASA's Solar Orbiter, ESA's BepiColombo, the JAXA-led Hinode, and even NASA's MAVEN at Mars are making simultaneous observations of activity stretching from the sun to Earth and beyond.

The pass also marked the midway point in the mission's 11th solar encounter, which began Feb. 20 and continues through March 2. The spacecraft checked in with mission operators at APL—where Parker Solar Probe was designed and built—on Feb. 28 to report that it was healthy and operating as expected.

Most of the data from this encounter will stream back to Earth from March 30 through May 1, though the team will get a glimpse of some readings when the spacecraft sends a limited amount of data this week.

Solar activity picks up

Parker Solar Probe is expected to dip back into the sun's outer atmosphere—the corona—continuing the solar wind and magnetic field readings it has taken since before it first "touched the sun" last year.

Along with that data, scientists eagerly anticipate a look at what Parker Solar Probe recorded from the large solar prominence on Feb. 15 that blasted tons of charged particles in the spacecraft's direction. Project Scientist Nour Raouafi of the Space Exploration Sector, said it was the largest event Parker Solar Probe has experienced during its first three-and-a-half years in flight.

"The shock from the event hit Parker Solar Probe head-on, but the spacecraft was built to withstand activity just like this—to get data in the most extreme conditions," he said. "And with the sun getting more and more active, we can't wait to see the data that Parker Solar Probe gathers as it gets closer and closer."

Assisted by a pair of orbit-shaping Venus flybys in August 2023 and November 2024, Parker Solar Probe will eventually come within 4 million miles (6.2 million kilometers) of the solar surface in December 2024 at speeds topping 430,000 miles per hour. Follow the probe's trek through the inner solar system.