So will these newcomers settle into orbit or simply pass us by? “Some of them will be captured by the Milky Way and will become satellites,” says François.

But saying exactly which ones is difficult because it depends on the exact mass of the Milky Way, and that is a quantity that is difficult for astronomers to calculate with any real accuracy. Estimates vary by a factor of two.

The discovery of the dwarf galaxy energies is significant because it forces us to re-evaluate the nature of the dwarf galaxies themselves.

As a dwarf galaxy orbits, the Milky Way’s gravitational pull will try to wrench it apart. In physics this is known as a tidal force. “The Milky Way is a big galaxy, so its tidal force is simply gigantic and it's very easy to destroy a dwarf galaxy after maybe one or two passages,” says François.

In other words, becoming a companion to the Milky Way is a death sentence for dwarf galaxies. The only thing that could resist our galaxy’s destructive grip is if the dwarf had a significant quantity of dark matter. Dark matter is the mysterious substance that astronomers think exists in the universe to provide the extra gravity to hold individual galaxies together.

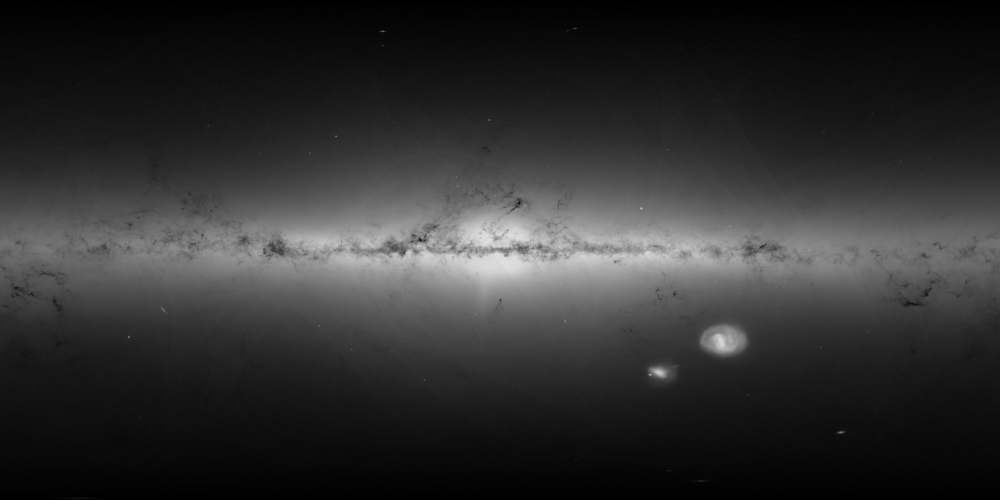

And so, in the traditional view that the Milky Way’s dwarfs were satellite galaxies that had been in orbit for many billions of years, it was assumed that they must be dominated by dark matter to balance the Milky Way’s tidal force and keep them intact. The fact that Gaia has revealed that most of the dwarf galaxies are circling the Milky Way for the first time means that they do not necessarily need to include any dark matter at all, and we must re-assess whether these systems are in balance or rather in the process of destruction.

“Thanks in large part to Gaia, it is now obvious that the history of the Milky Way is far more storied than astronomers had previously understood. By investigating these tantalising clues, we hope to further tease out the fascinating chapters in our galaxy’s past,” says Timo Prusti, Gaia Project Scientist, ESA.