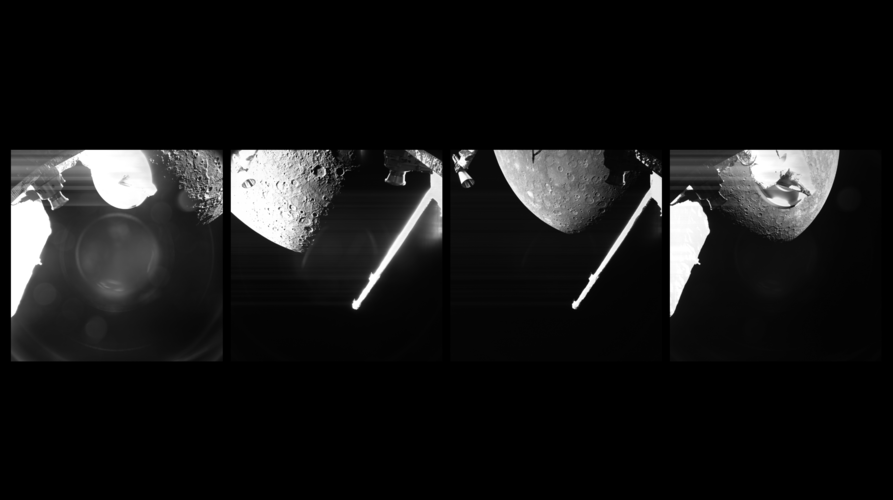

Although the cratered surface looks rather like Earth’s Moon at first sight, Mercury has a much different history. Once its main science mission begins, BepiColombo’s two science orbiters – ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter and JAXA’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter – will study all aspects of mysterious Mercury from its core to surface processes, magnetic field and exosphere, to better understand the origin and evolution of a planet close to its parent star. For example, it will map the surface of Mercury and analyse its composition to learn more about its formation. One theory is that it may have begun as a larger body that was then stripped of most of its rock by a giant impact. This left it with a relatively large iron core, where its magnetic field is generated, and only a thin rocky outer shell.

Mercury has no equivalent to the ancient bright lunar highlands: its surface is dark almost everywhere, and was formed by vast outpourings of lava billions of years ago. These lava flows bear the scars of craters formed by asteroids and comets crashing onto the surface at speeds of tens of kilometers per hour. The floors of some of the older and larger craters have been flooded by younger lava flows, and there are also more than a hundred sites where volcanic explosions have ruptured the surface from below.