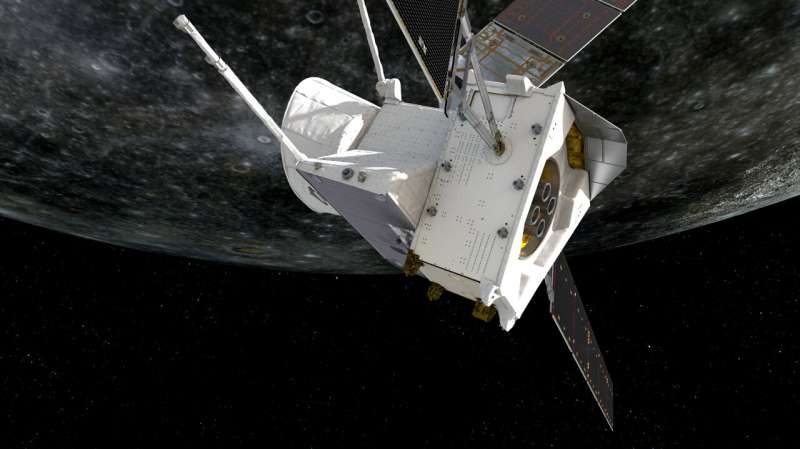

The mission comprises two science orbiters which will be delivered into complementary orbits around the planet by the Mercury Transfer Module in 2025. The ESA-led Mercury Planetary Orbiter and the JAXA-led Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, Mio, will study all aspects of this mysterious inner planet from its core to surface processes, magnetic field and exosphere, to better understand the origin and evolution of a planet close to its parent star.

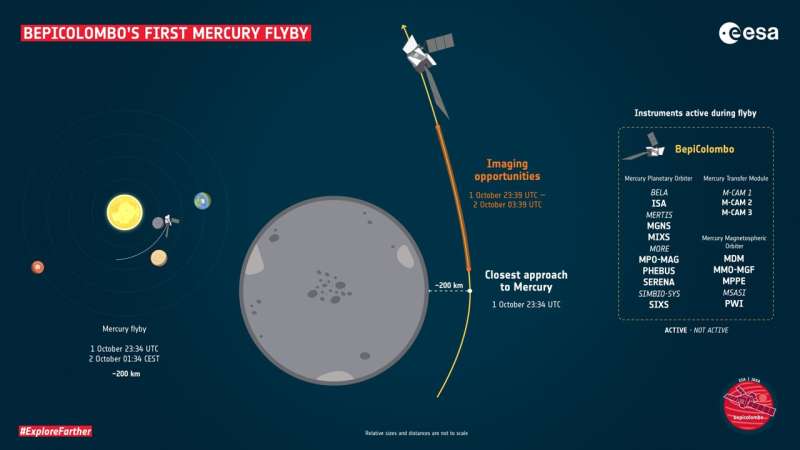

BepiColombo will make use of nine planetary flybys in total: one at Earth, two at Venus, and six at Mercury, together with the spacecraft's solar electric propulsion system, to help steer into Mercury orbit.

On track for Mercury slingshot

Gravitational flybys require extremely precise deep-space navigation work, ensuring that the spacecraft is on the correct approach trajectory.

One week after BepiColombo's last flyby on 10 August, a correction maneuver was performed to nudge the craft a little for this first flyby of Mercury, targeting an altitude of 200 km. At present, the craft is predicted to pass the innermost planet at 198 km, and small adjustments can easily be made with solar electric propulsion maneuvers after the swing-by. As BepiColombo is more than 100 million km away from Earth, with light taking 350 seconds (about six minutes) to reach it, being on target to within just two kilometers is no easy feat.

"It is because of our remarkable ground stations that we know where our spacecraft is with such precision. With this information, the Flight Dynamics team at ESOC know just how much we need to maneuver, to be in the right place for Mercury's gravitational assist," explains Elsa Montagnon, Spacecraft Operations Manager for the mission.

"As is often the case, our mission's path has been planned so meticulously that no further correction maneuvers are expected for this upcoming flyby. BepiColombo is on track."

First glimpse of Mercury

During the flybys it is not possible to take high-resolution imagery with the main science camera because it is shielded by the transfer module while the spacecraft is in cruise configuration. However, two of BepiColombo's three monitoring cameras (MCAMs) will be taking photos from about five minutes after the time of close approach and up to four hours later. Because BepiColombo is arriving on the planet's nightside, conditions are not ideal to take images directly at the closest approach, thus the closest image will be captured from a distance of about 1000 km.

The first image to be downlinked will be from about 30 minutes after closest approach, and is expected to be available for public release at around 08:00 CEST on Saturday morning. The close approach and subsequent images will be downlinked one by one during Saturday morning.

The cameras provide black-and-white snapshots in 1,024 x 1,024 pixel resolution, and are positioned on the Mercury Transfer Module such that they also capture the spacecraft's solar arrays and antennas. As the spacecraft changes its orientation during the flyby, Mercury will be seen passing behind the spacecraft structural elements.

In general, MCAM-2 will point towards the northern hemisphere of Mercury, while MCAM-3 will point towards the southern hemisphere. During the half hour following the close approach, imaging will alternate between the two cameras. Later imaging will be performed by MCAM-3.

For the closest images it should be possible to identify large impact craters on the planet's surface. Mercury has a heavily cratered surface much like the appearance of Earth's Moon, plotting its 4.6 billion year history. Mapping the surface of Mercury and analyzing its composition will help scientists understand more about its formation and evolution.

Even though BepiColombo is in 'stacked' cruise configuration for the flybys, it will be possible to operate some of the science instruments on both planetary orbiters, allowing a first taste of the planet's magnetic, plasma and particle environment.

"We're really looking forward to seeing the first results from measurements taken so close to Mercury's surface," says Johannes Benkhoff, ESA's BepiColombo project scientist. "When I started working as project scientist on BepiColombo in January 2008, NASA's Messenger mission had its first flyby at Mercury. Now it's our turn. It's a fantastic feeling!"

Explore further