And even though Perseus was a mythical Greek hero, the meteors have little to do with myth, said Vida.

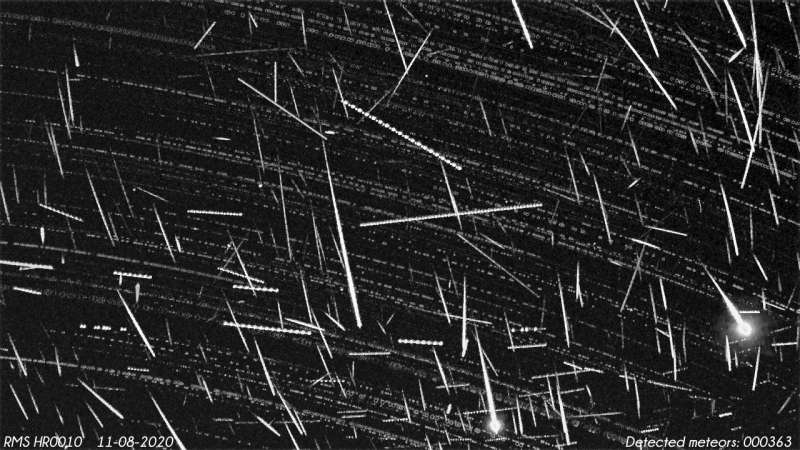

The Perseids are millimeter-sized dust particles, which enter the atmosphere at a hypersonic speed of 60 kilometers per second. (That's about 30 times faster than the F-35 fighter jet!). But despite their minuscule size, they have so much energy that when they collide with air molecules, electrons from the atmospheric atoms and those released from the meteoroid can be excited or even 'ripped' away entirely from their host atom and this makes the atoms glow.

"It only takes a brief moment before the atoms capture an electron and emit light, which is when you can see a glowing trail in the sky," said Vida, project lead of the Global Meteor Network.

The Perseids will be visible this year as the new moon will occur on August 8, only a few days prior to the peak on August 12. Vida says provided the weather is good and you are away from big city centers, the sky will be dark and perfect for viewing.

"The best show will be just before sunrise on either August 12th or August 13th," he said. "But if you are planning to observe in the evening hours on August 11th or 12th, start after 10pm and look either east or north-west. If you can locate the Big Dipper in the sky, look in its direction and you are bound to see some Perseids."

For best observing, Vida said allow your eyes to adjust to the dark for at least 10 minutes.

"Avoid looking at your phone, or if you do, make sure to crank that blue light filter to the max as red light will not interfere with your night vision," he said.

Collateral damage

The Perseids are an amazing spectacle, yes, but they are also potentially dangerous.

During an outburst in 1993, a Perseid meteor destroyed a very expensive satellite. Four years prior, the European Space Agency launched Olympus-1, the largest civilian telecommunications satellite ever built at that time, costing $850 million.

"Even though dust particles that cause meteors are very sparse in space, given enough time and a large surface area, a satellite is bound to get hit," said Vida. "And this time, it did."

The impact formed a plasma cloud that shorted the spacecraft's attitude control system, Vida explained. Its operators were able to stop it from spinning out of control, but they had depleted all of its fuel and the satellite was put out of commission.

A member of the Western Meteor Physics Group, led by Western's Canada Research Chair in planetary small bodies Peter Brown, Vida said one of the most important aspects of the team's research is long-term monitoring of meteor showers and building predictive models of meteor shower activity over time.

"By monitoring and modeling, we can give satellite operators a heads up that a meteor shower outburst is coming and that they should orient their spacecraft as to minimize the cross-sectional area with respect to the direction where the meteors are traveling."