The presence or absence of a shield matters because magnetic shields protect astronomical bodies from harmful solar radiation. And the team's findings contradict some longstanding assumptions.

"This is a new paradigm for the lunar magnetic field," says first author John Tarduno, the William R. Kenan, Jr., Professor of Geophysics in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and dean of research for Arts, Sciences & Engineering at Rochester.

Did the moon ever have a magnetic shield?

For years, Tarduno has been a leader in the field of paleomagnetism, studying the development of Earth's magnetic shield as a means to understanding planetary evolution and environmental change.

Earth's magnetic shield originates deep within the planet's core. There, swirling liquid iron generates electric currents, driving a phenomenon called the geodynamo, which produces the shield. The magnetic shield is invisible, but researchers have long recognized that it is vital for life on Earth's surface because it protects our planet from solar wind—streams of radiation from the sun.

But has Earth's moon ever had a magnetic shield?

While the moon has no magnetic shield now, there has been debate over whether or not the moon may have had a prolonged magnetic shield at some point in its history.

"Since the Apollo missions, there has been this idea that the moon had a magnetic field that was as strong or even stronger than Earth's magnetic field at around 3.7 billion years ago," Tarduno says.

The belief that the moon had a magnetic shield was based on an initial dataset from the 1970s that included analyses of samples collected during the Apollo missions. The analyses showed that the samples had magnetization, which researchers believed was caused by the presence of a geodynamo.

But a couple of factors have since given researchers pause.

"The core of the moon is really small and it would be hard to actually drive that kind of magnetic field," Tarduno explains. "Plus, the previous measurements that record a high magnetic field were not conducted using heating experiments. They used other techniques that may not accurately record the magnetic field."

When lunar samples meet lasers

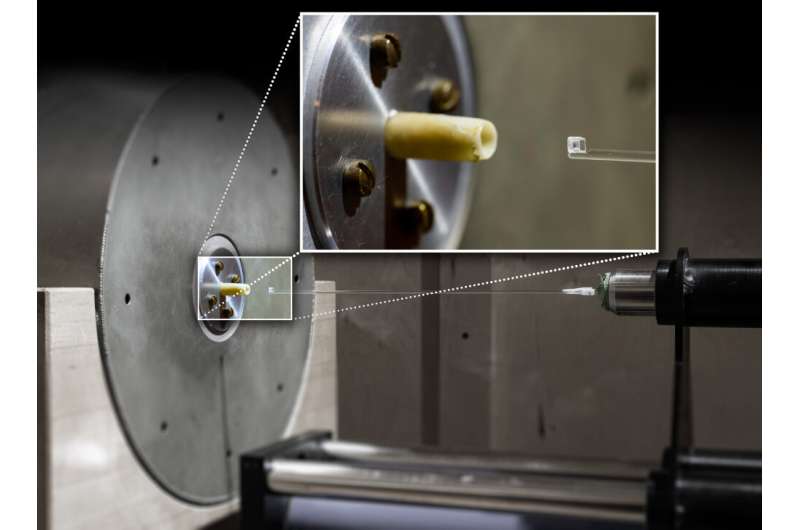

Tarduno and his colleagues tested glass samples gathered on previous Apollo missions, but used CO2 lasers to heat the lunar samples for a short amount of time, a method that allowed them to avoid altering the samples. They then used highly sensitive superconducting magnetometers to more accurately measure the samples' magnetic signals.

"One of the issues with lunar samples has been that the magnetic carriers in them are quite susceptible to alteration," Tarduno says. "By heating with a laser, there is no evidence of alteration in our measurements, so we can avoid the problems people may have had in the past."

The researchers determined that the magnetization in the samples could be the result of impacts from objects such as meteorites or comets—not the result of magnetization from the presence of a magnetic shield. Other samples they analyzed had the potential to show strong magnetization in the presence of a magnetic field, but didn't show any magnetization, further indicating that the moon has never had a prolonged magnetic shield.

"If there had been a magnetic field on the moon, the samples we studied should all have acquired magnetization, but they haven't," Tarduno says. "That's pretty conclusive that the moon didn't have a long-lasting dynamo field."

Lack of magnetic shield means an abundance of elements

Without the protection of a magnetic shield, the moon was susceptible to solar wind, which may have caused a variety of volatiles—chemical elements and compounds that can be easily evaporated—to become implanted in the lunar soil. These volatiles may include carbon, hydrogen, water, and helium 3, an isotope of helium that is not present in abundance on Earth.

"Our data indicates we should be looking at the high end of estimates of helium 3 because a lack of magnetic shield means more solar wind reaches the lunar surface, resulting in much deeper reservoirs of helium 3 than people thought previously," Tarduno says.

The research may help inform a new wave of lunar experiments based on data that will be gathered by the Artemis mission. Data from samples gathered during the mission will allow scientists and engineers to study the presence of volatiles and better determine if these materials can be extracted for human use. Helium 3, for instance, is currently used in medical imaging and cryogenics and is a possible future fuel source.

A lack of magnetic shielding also means that ancient lunar soils may hold records of past solar wind emissions. Analyzing cores of soil samples could therefore provide scientists with a better understanding of the evolution of the sun.

"With the background provided by our research, scientists can more properly think about the next set of lunar experiments to perform," Tarduno says. "These experiments may focus on current lunar resources and how we could use them and also on the historical record of what is trapped in the lunar soil."