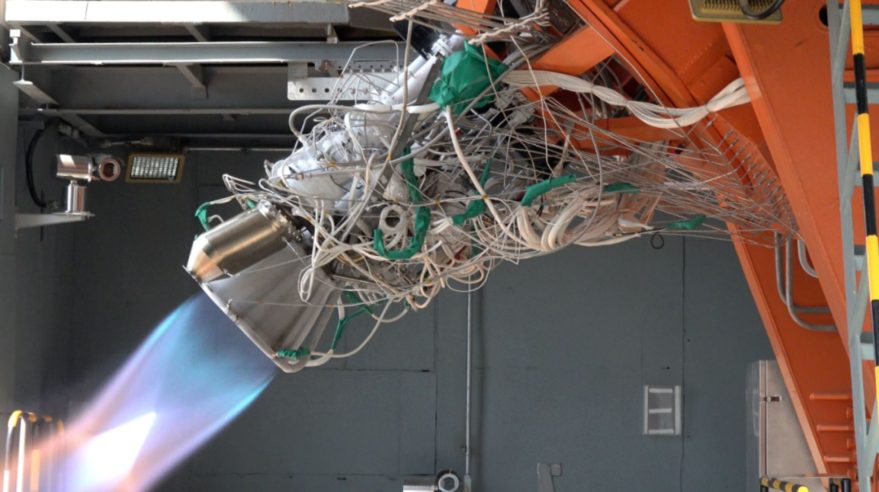

Beijing Deep Blue Aerospace Technology Co., Ltd., carried out a 10-second static fire test of the 7.3-meter-high “Nebula-M” technology verification test vehicle, the company announced July 13.

Deep Blue Aerospace plans to follow up with a variable thrust test before attempting vertical takeoff, vertical landing tests with the Nebula-M. No timeline for the attempts was provided.

The Nebula-M uses a Leiting-5 (Thunder 5) kerosene-liquid oxygen, electric-pump-fed engine and will attempt meter- and 100-meter-level hops. The tests can be considered analogous to SpaceX’s Grasshopper experimental flights as a step towards reusable rockets.

The hop tests will pave the way for an orbital launch of the reusable Nebula-1 launch vehicle. The 2.25-meter-diameter Nebula-1 is to be capable of lifting 500 kilograms to 500 km Sun-synchronous orbit. A larger 3.35-meter-diameter Nebula-2 launcher capable of sending 4,500 kilograms to low Earth orbit is also in development.

The test is one of a number of efforts by Chinese companies to develop reusable, cost-reducing liquid launch vehicles. Alongside Deep Blue Aerospace, iSpace is working towards hop tests using a test stage for the reusable Hyperbola-2 methane-liquid oxygen launch vehicle. In April the firm conducted lengthy variable thrust hot fire tests of its Jiaodian-1 engine.

Landspace, which made its first and so far only launch attempt with the Zhuque-1 solid rocket in 2018, is expected to conduct the first launch of its Zhuque-2 methalox rocket this year. Founder Zhang Changwu said in April that the firm would choose an opportunity to launch within the next six months.

Zhuque-2 will initially be expendable, but Landspace is looking to upgrade the engines to make the launcher VTVL-capable and reusable.

These endeavors are illustrative of the level of ambition within China’s commercial space sector, while their success or failure will be indicative of progress and capabilities so far made. The developments are also a reaction to changes in the launch sector initiated in the United States, namely the emergence of private launch companies and shift to reusability.

Crowded commercial field

Four Chinese rocket companies have attempted orbital launches following a Chinese government decision to open up the space sector to private capital in 2014. Two of the companies—iSpace and Galactic Energy—successfully inserted payloads into orbit.

So far however all attempts have used simpler and expendable solid rockets, with liquid rockets posing more complex challenges. The upcoming tests by Deep Blue Aerospace will however not be the first hop tests by a Chinese company. In August 2019 Linkspace performed a successful 300-meter-altitude VTVL test. The firm soon after signed a deal with Jiuzhou Yunjian for engines for an orbital launcher, but has since been silent, except for a recruitment notice posted in March.

Galactic Energy is also developing a reusable launcher. The kerolox Pallas-1 is slated for a test launch in late 2022. The Beijing-based firm is expected first to follow up a successful first launch with more commercial missions of the Ceres-1 solid rocket.

A number of China’s commercial launch companies have attracted huge funding rounds, despite a large number of actors competing for a share of an uncertain commercial market.

More than ten firms—Landspace, OneSpace, iSpace, Linkspace, Galactic Energy, Deep Blue Aerospace, Space Pioneer, Space Transportation, Aerospace Propulsion, Seres Space Exploration Technology, Oriental Space, Spacetrek and Rocket Pi—have plans to develop launch vehicles.

China Rocket and Expace, spinoffs from huge state-owned space contractors, have additionally launched solid rockets. Both are also planning to develop reusable liquid launchers. CAS Space, an offshoot from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, has also entered the sector.

Initiatives such as the national satellite internet project could provide launch contract opportunities for commercial outfits.

Firms have been supported through a national strategy of civil-military fusion. This includes facilitating the transfer of restricted technologies to approved firms in order to promote innovation in dual-use technologies.

The State Administration for Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense (SASTIND) has also issued guidance on the development of launch vehicles and small satellites as part of an apparent effort to create a clear regulatory framework for commercial space activities.

The country’s main space contractor, the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corp. (CASC), is also exploring reusability. The new Long March 8, derived from the expendable Long March 7 and older Long March 3B technologies, had a first flight in December and is expected to be developed into a VTVL launcher. First stage VTVL hop tests are expected this year. Grid fin and other tests have also been carried out with older Long March 2C rockets, and variants of the Long March 6 are expected to be reusable.

In the longer term China has stated that it is targeting smart, recoverable and reusable launch vehicles by around 2035. Design concepts for China’s future super heavy-lift launcher, the Long March 9, appear to be shifting from the established Long March-style with side boosters to a single core version with clustered engines more amenable to first stage reusability, according to a presentation from a senior Chinese rocket designer.