During the flight—designed to test the helicopter's ability to serve as an aerial scout—Ingenuity soared over a dune field nicknamed "Séítah." Perseverance is making a detour south around those dunes, which would be too risky for the six-wheeled rover to try crossing.

The color images from Ingenuity, taken from a height of around 33 feet (10 meters), offer the rover team much greater detail than they get from the orbiter images they typically use for route planning. While a camera like HiRISE (the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment) aboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter can resolve rocks about 3 feet (1 meter) in diameter, missions usually rely on rover images to see smaller rocks or terrain features.

"Once a rover gets close enough to a location, we get ground-scale images that we can compare to orbital images," said Perseverance Deputy Project Scientist Ken Williford of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. "With Ingenuity, we now have this intermediate-scale imagery that nicely fills the gap in resolution."

Below are a few of Ingenuity's images, which completed the long journey back to Earth on July 8.

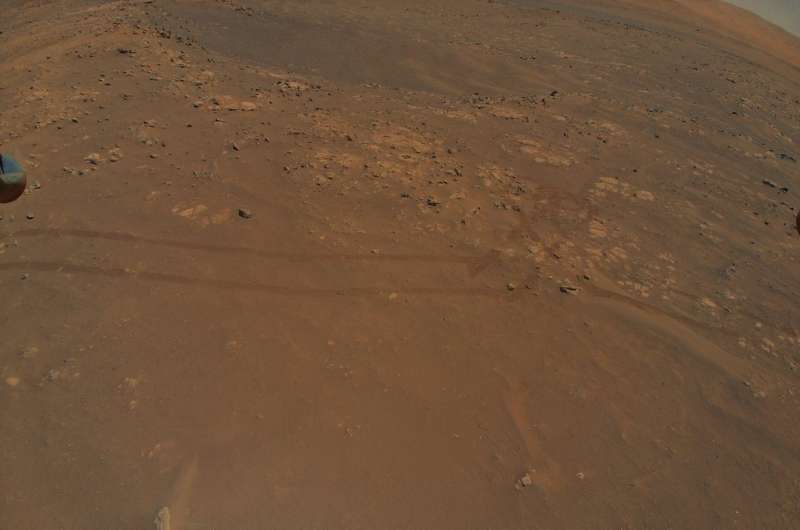

Raised ridges

Ingenuity (its shadow is visible at the bottom of this image) offered a high-resolution glimpse of rock features nicknamed "Raised Ridges." They belong to a fracture system, which often serve as pathways for fluid to flow underground.

Here in Jezero Crater, a lake existed billions of years ago. Spying the ridges in images from Mars orbiters, scientists have wondered whether water might have flowed through these fractures at some point, dissolving minerals that could help feed ancient microbial colonies. That would make them a prime location to look for signs of ancient life—and perhaps to drill a sample.

The samples Perseverance takes will eventually be deposited on Mars for a future mission that would take them to Earth for in-depth analysis.

"Our current plan is to visit Raised Ridges and investigate it close up," Williford said. "The helicopter's images are by far better in resolution than the orbital ones we were using. Studying these will allow us to ensure that visiting these ridges is important to the team."

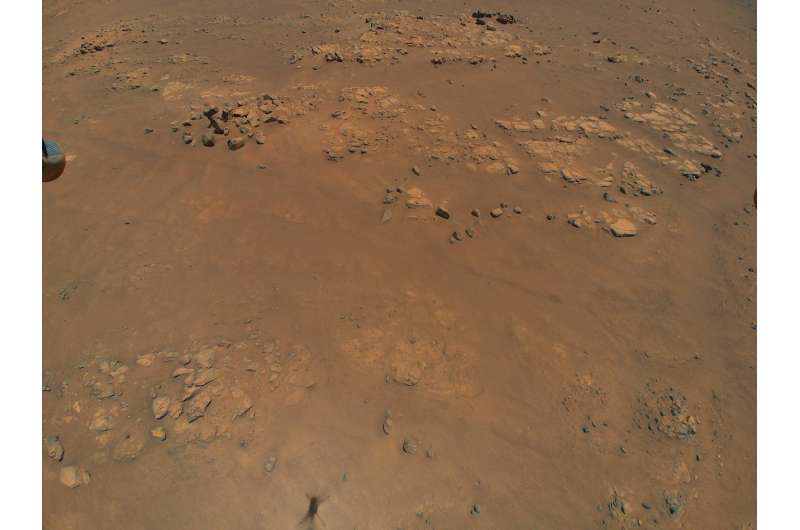

Dunes

Sand dunes like the ones in this image keep rover drivers like JPL's Olivier Toupet awake at night: Knee- or waist-high, they could easily cause the two-ton rover to get stuck. After landing in February, Perseverance scientists asked whether it was possible to make a beeline across this terrain; Toupet's answer was a hard no.

"Sand is a big concern," said Toupet, who leads the team of mobility experts that plans Perseverance's drives. "If we drive downhill into a dune, we could embed ourselves into it and not be able to get back out."

Toupet is also the lead for Perseverance's newly tested AutoNav feature, which uses artificial intelligence algorithms to drive the rover autonomously over greater distances than could be achieved otherwise. While good at avoiding rocks and other hazards, AutoNav can't detect sand, so human drivers still need to define "keep-out zones" around areas that could entrap the rover.

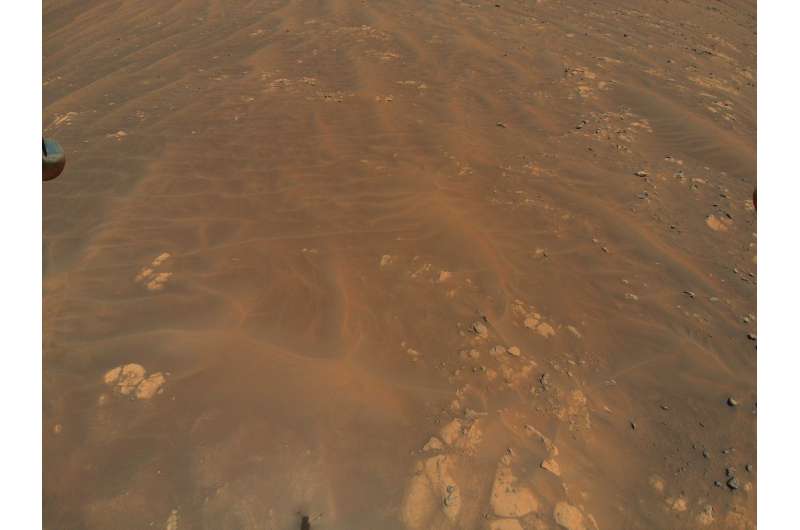

Bedrock

Without Ingenuity, visible in silhouette at the bottom of this next image, Perseverance's scientists would never get to see this section of Séítah so clearly: It's too sandy for Perseverance to visit. The unique view offers enough detail to inspect these rocks and get a better understanding of this area of Jezero Crater.

As the rover works its way around the dune field, it may make what the team calls a "toe dip" into some scientifically compelling spots with interesting bedrock. While Toupet and his team wouldn't attempt a toe dip here, the recent images from Ingenuity will allow them to plan potential toe-dip paths in other regions along the route of Perseverance's first science campaign.

"The helicopter is an extremely valuable asset for rover planning because it provides high-resolution imagery of the terrain we want to drive through," said Toupet. "We can better assess the size of the dunes and where bedrock is poking out. That's great information for us; it helps identify which areas may be traversable by the rover and whether certain high-value science targets are reachable."