If you've had the pleasure of seeing an open sky on a clear, dark night, you've probably been struck by the sheer number of stars. Perhaps you've even tried to count them up. (If not, a hint: There are somewhere around five thousand visible to the naked eye from Earth.) But the real wonder is that our speckled night sky represents only the tiniest sample of what's truly out there.

To get a rough estimate of the total number of stars in the universe, scientists have calculated the average number of stars in a galaxy—some estimates put it at about 100 million, though it could be 10 or more times higher—and multiplied it by the number of galaxies, taken to be about 2 trillion (also very tentative). That gets you one hundred quintillion stars (or 1 with 21 zeroes after it). That's more than 10 stars for every grain of sand on Earth (estimated at about seven and a half quintillion).

But even that astronomically high number may be an underestimate. That calculation assumes all, or at least most, stars are inside galaxies. Based on recent findings, that may not be quite true—and it's what the CIBER-2 mission is trying to figure out.

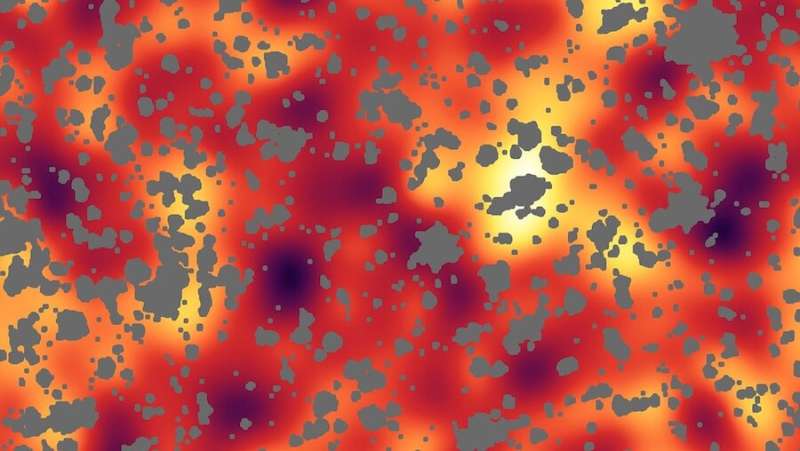

The CIBER-2 instrument, like the earlier CIBER instrument it's based on, will launch aboard a sounding rocket—a small suborbital rocket that carries scientific instruments on brief trips into space before falling back to Earth for recovery. Once above Earth's atmosphere, CIBER-2 will survey a patch of sky about 4 square degrees—for reference, the full Moon takes up about half a degree—that includes dozens of galaxy clusters. It won't count stars, but it will detect the diffuse, cosmos-filling glow known as the extragalactic background light.

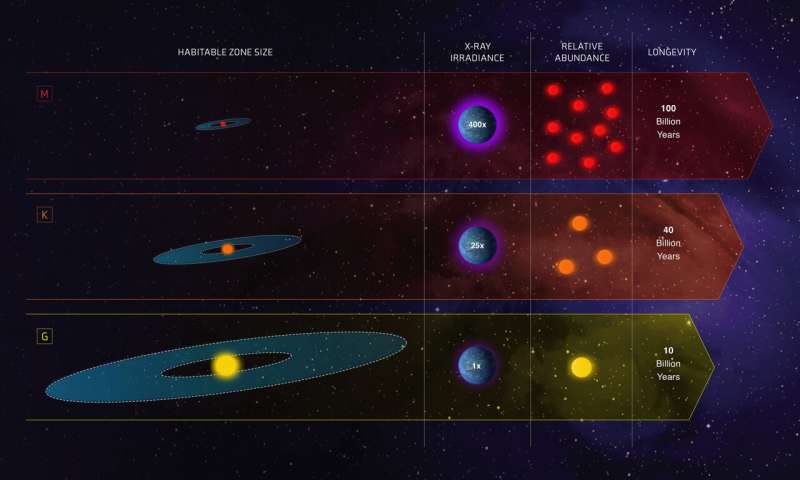

"This background glow is the total light produced over cosmic history" said Jamie Bock, professor of physics at Caltech in Pasadena, California, and lead researcher for CIBER's first four flights. That background light spans a range of wavelengths, but CIBER-2 will focus on a small portion called the cosmic infrared background, or CIB. Much of the CIB is thought to come from M and K dwarfs, the most common star types in the universe, though that's not the only contributor. "Our method measures the total light, including from sources we haven't identified yet," Bock said.

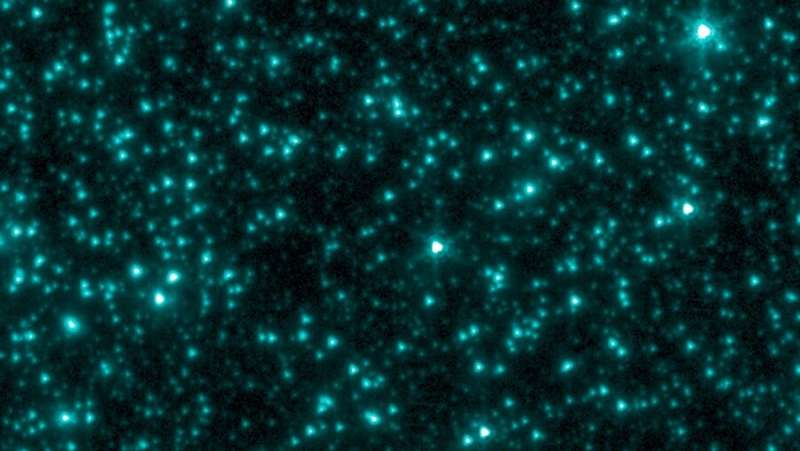

When you can't count up individual stars in a galaxy, the CIB's brightness should give you a good estimate of how many M and K dwarfs there are. And if all those stars are inside the galaxy, that light should be brightest toward its center. In 2007, scientists used NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope to look at galaxy clusters and make this type of measurement.

But Spitzer observed more light than was expected from known galaxy populations—the fluctuations in brightness of the CIB hinted that they were missing something.

Bock and Zemcov—at the time a post-doctoral researcher but now the principal investigator for CIBER-2—flew the first CIBER mission to check those results with a telescope better optimized for the task.

"So we did that measurement, and we came up with an answer that was uncomfortable," said Zemcov. "There were a lot more fluctuations than we were expecting—one explanation is there is more light coming from outside of galaxies than we had thought."

The extra light, they believe, may be from the glimmer of stray dwarf stars. These stars could have been flung out of their home galaxy when it merged with another, a process known as tidal stripping. Such far-flung stars are known to surround the Milky Way, though current counts suggest there's not nearly enough of them to produce the signal CIBER measured.

"More and more research suggests that there are a significant number of stars of this type outside of galaxies," Zemcov said.

But alternative hypotheses for this excess light have arisen. "We know some of that light comes from galaxies, and some the first stars ever to shine, even though they're long gone now," said Bock. Some light from our own galaxy could even pollute the measurements, though the CIBER team has done their best to filter it out. There are also more exotic possibilities, like direct-collapse black holes from the early universe—massive clouds of gas that collapsed into black holes without becoming stars first—whose ultraviolet light would have stretched across expanding space into the longer infrared wavelengths we see today. CIBER-2 was designed to help settle the matter by distinguishing these possibilities.

Light from extragalactic M and K dwarfs should spill over into visible range, so CIBER-2 was designed to observe an expanded range of wavelengths—from the near-infrared to green visible light—to see it if it's there. CIBER-2 can also distinguish light from the first galaxies and stars or early direct-collapsing black holes: Both should have a characteristic portion of their total light missing, the part absorbed by the thick fog of intergalactic hydrogen in the early universe.

For now, all the possibilities remain on the table. But if our star count should indeed go up, CIBER-2's results could soon tell us.

"There are hints that we are definitely not catching all the stuff in the universe. And the more people look, the more they see," said Zemcov.