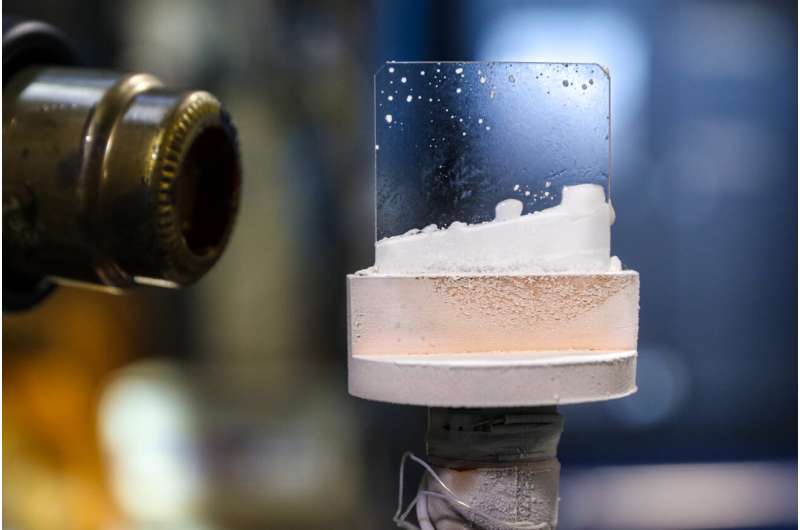

That's exactly what scientists from the US Department of Energy's (DOE's) Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, are working on at the ORNL Spallation Neutron Source (SNS). They lowered the temperature of a single crystal sapphire plate to 25 K (about minus 414 degrees Fahrenheit), placed it in a vacuum chamber, and added just a few molecules at a time of water–in this case, heavy water (D2O)–to the plate. Then they observed how the ice structure changed with varying temperature before it finally formed crystalline ice. The team next plans to simulate the solar system's icy bodies by bombarding the sample with electron radiation to determine how this influences the ice structure.

"The experiment produced a layer of amorphous ice similar to the ice that makes up most of the water throughout the universe," said Chris Tulk, ORNL neutron scattering scientist. "This is the same type of ice that could have formed on the extremely cold permanently shadowed regions of the Moon, on the polar regions of Jupiter's moon Europa, and within the material between the stars in our galaxy, known as dense molecular clouds. Although much of the ice has by now probably crystallized on the warmer bodies, the fresh ice on colder bodies and in deep space is likely still amorphous."

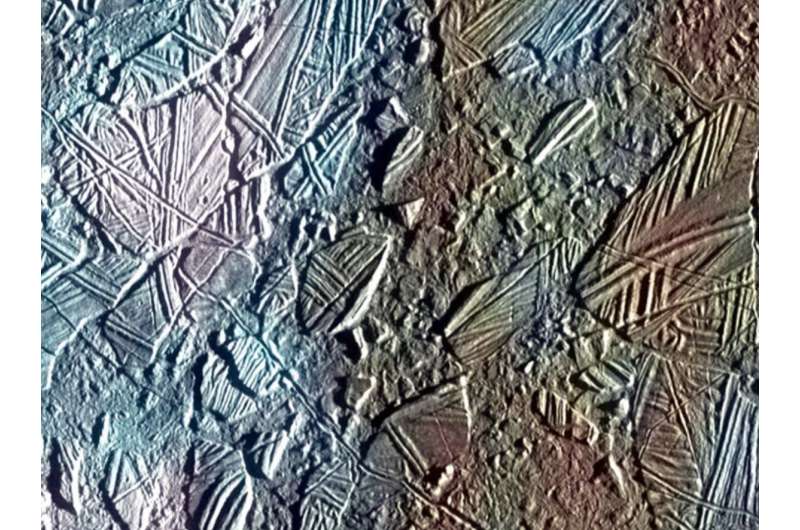

The scientists hope to answer questions such as how much of the ice on the surface of Europa, Jupiter's second smallest moon, could be amorphous ice as a result of the surface being irradiated by charged particles produced by Jupiter's magnetic field.

"This information could help us better interpret the science data from the Europa Clipper spacecraft and also provide some clues about how water ice evolves in various parts of the universe," said Murthy Gudipati, senior research scientist at JPL. "With a launch date planned for 2024, the goal of the Europa Clipper mission is to assess Europa's habitability by studying its atmosphere, surface, and interior, including liquid water beneath the icy crust that could potentially support life."

The team's initial experiments were performed on the Spallation Neutrons and Pressure (SNAP) diffractometer at SNS, an instrument typically used for high-pressure experiments, but which the scientists configured to mimic the low-pressure, extreme cold and high radiation environment of space. Future experiments will employ inelastic neutron scattering on the VISION instrument to study the dynamics of the amorphous ice as it forms. The experiments will also employ electron bombardment to study the changes in these exotic ice forms in a space radiation environment.