Work is underway on two new military satellite systems designed to replace the most critical capabilities of the venerable Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP). But the new satellites aren’t slated to begin operations until 2024 and 2026, a timeline just barely in sync with how much longer the U.S. Space Force thinks it can keep DMSP going.

The Space Force’s most recent DMSP reliability assessment concluded that the satellites will reach “mission end-of-life” between late 2023 and sometime in 2026.

DoD’s game plan has little margin for error. If the new satellites run late, or if DMSP goes dark sooner than expected, the Space Force and its partners could be looking at gaps in critical weather data used by military planners.

U.S. Space Force Gen. David Thompson underscored the military importance of weather satellites when he testified before Congress in 2019 as vice commander of Air Force Space Command. “Every DoD operational mission begins with a weather briefing; either space weather, terrestrial weather, or both,” Thompson said. “The data required for DoD missions is often unique and necessitates 24/7 global ability to forecast weather in austere and denied environments.”

Space Force officials don’t appear worried about the partly cloudy forecast hanging over its weather satellite programs. If anything, the military’s decades-long effort to replace its Cold war-era satellite system is on its firmest footing yet.

And by waiting so long to finally get going, DoD may profit from Moore’s law and the small satellite instruments it makes possible.

FROM DMSP TO NPOESS

Since its beginnings more a half-century ago as a highly classified project, DMSP has the distinction of being the nation’s longest running production satellite program.

The four operational DMSP satellites currently orbiting the planet 14 times a day launched between 1999 and 2009. Built by longtime contractor Lockheed Martin, the 5D-3 block of DMSP satellites were designed to last five years. As such, the oldest of the four, DMSP 5D-3 /F15, has been living on borrowed time for roughly 17 years.

The Space Force intends to replace DMSP with at least two different satellite systems — one for passive microwave sensing, and one for visible and infrared imaging.

So far, only the microwave satellite is under firm contract, with a launch targeted for the tail end of 2023. The Space Force is also banking on launching at least one visible/infrared satellite prototype by the end of 2023 to set the stage for a proposed 2026 deployment of operational versions.

The current effort to replace DMSP is a continuation of a saga that dates back to 1994. That’s when the White House, in directed the Defense Department, NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to merge weather satellite requirements in order to reduce unnecessary duplication and save money. The result was the National Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite System (NPOESS), a tri-agency program that ultimately selected Northrop Grumman as prime contractor.

Envisioned as a six-satellite successor to DMSP and civilian-led Polar Operational Environmental Satellites (POES) funded by NOAA and its European counterpart Eumetsat, the $6.5 billion NPOESS program was slated to launch its first state-of-the-art satellite in 2008.

Management problems and instrument delays pushed the schedule repeatedly to the right, driving up costs and triggering three congressionally mandated Nunn-McCurdy termination reviews. By the time the White House pulled the plug on NPOESS in 2010, its price tag had ballooned to $15 billion even as the number of satellites was scaled back to four.

After the demise of NPOESS, NASA and NOAA proceeded with the 2011 launch of the NPOESS Preparatory Project (since renamed the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership) and co-developed the follow-on Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS). The first JPSS satellite, built by Suomi NPP contractor Ball Aerospace, launched in 2017. Three more JPSS satellites, now under contract to Northrop Grumman with instrument contributions from Ball, Raytheon and L3Harris, are slated to launch between 2022 and 2032.

The Defense Department’s post-NPOESS efforts to replace its Cold War-era DMSP satellites, in contrast, proceeded in fits and starts before recently converging on the current plan.

OFF TO SHAKY START

In 2011, the Air Force embarked on the Defense Weather Satellite System (DWSS) program and awarded NPOESS prime contractor Northrop Grumman a $429 million contract to build a DMSP successor that could be ready to launch in 2018. DWSS would carry an optical and infrared imager, a microwave sensor, and a space weather payload, leveraging the government’s NPOESS investments. Congress balked at the program’s cost and strategy, however, and directed the Air Force in 2012 to terminate DWSS and make a fresh start.

To buy itself time while it went back to the drawing board, the Air Force started making plans to refurbish and launch two DMSPs that Lockheed Martin had previously put in storage.

Further complicating matters, a fight with Congress soon ensued over Air Force plans to shut down the Operationally Responsive Space Office (ORS) established several years earlier to pioneer the development of low-cost military satellites. To help keep ORS in business, Congress in 2013 gave the office money to build a small weather satellite. In 2015, ORS teamed with NASA to develop ORS-8, a visible and infrared imaging satellite that would focus on cloud characterization. In 2018, the ORS-8 contract was awarded to Sierra Nevada Corp. but the award was rescinded following a bid protest. Soon after, the Air Force canceled the project.

With NPOESS canceled following 15 years of costly effort, DWSS shot down by Congress before it could really get going, and the ORS-8 episode pointing the way to a low-cost visible and infrared solution, the Air Force was finally converging on its current strategy: separate satellite systems for microwave sensors and optical and infrared imagers.

In the meantime, the Air Force and Lockheed Martin finished refurbishing one of the two DMSP satellites it had in storage — DMSP 5D-3/F19 — and launched it in early 2014 to refresh the aging constellation.

Lockheed Martin still had one DMSP satellite — DMSP 5D-3/F20 — in storage in Sunnyvale, California, but Congress soon pushed the Air Force to get moving on its new satellites and scrap the hangar queen to save tens of millions in annual storage costs.

DMSP 5D-3/F20 got a temporary stay of execution when its twin, F19, suffered a crippling power failure in February 2016, after just 22 months in orbit.

Congress ultimately refused to budge. It stripped the DMSP storage money from the Air Force’s 2016 budget and denied the $120 million the Air Force requested to pay for F20’s planned 2018 launch. DMSP, the nation’s longest running satellite production program, was finally canceled.

“The Hill was trying to send a message that they didn’t have a tremendous concern about canceling DMSP because three years prior they had given the Air Force $123 million to build the next program,” said former congressional staffer Mike Tierney, an analyst at the aerospace and defense consulting firm Velos.

With no funding to launch or continue storing its last DMSP satellite, the Air Force in late 2017 put F20 on permanent display at the Space and Missile Systems Center’s Los Angeles headquarters.

The Defense Department still had five DMSPs in service as recently as last year, when it finally retired the 23-year-old DMSP 5D-2/F14 — the last of nine 5D-2 series with a failure-prone battery assembly implicated in three on-orbit explosions of decommissioned DMSP satellites between 2004 and late 2016.

Down to four operational DMSPs launched between 1999 and 2009, the Space Force is counting on continued good fortune — and ongoing cooperation with NOAA and European allies — to keep a sharp eye on the weather while it waits for reinforcements.

An assessment the Space Force completed in December concluded that the DMSP constellation will reach its mission end-of-life between late 2023 and sometime in 2026, “with usable and acceptable user products through at least a median estimate of [the first quarter of 2025].”

DMSP DISAGGREGATED

By 2017, amid the tug-of-war with Congress over the smallsat philosophy of ORS and whether to launch the very last of the several dozen DMSP satellites built since the early 1960s, the Air Force finally settled on a plan to split the legacy system’s capabilities into two programs. A pair of so-called Weather System Follow-on Microwave (WSF-M) satellites in a 1,300-kilometer polar orbit will measure ocean winds, rain, snow, ice and soil moisture, and monitor space weather; and a still loosely defined constellation of polar-orbiting optical and infrared satellites to provide imagery of cloud cover and other conditions pertinent to military operations.

Of the two sets of satellites, only WSF-M is currently under firm contract.

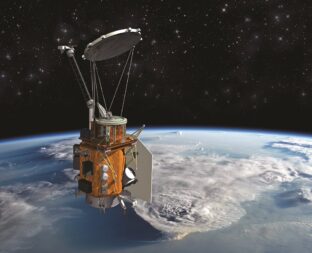

The Space and Missile Systems Center (SMC), now part of Space Force, selected Ball Aerospace in 2017 to design WSF-M, and awarded the company a $349 million fixed-price contract in 2018 to build the first of two planned satellites.

The WSF-M satellite passed a critical design review in April 2020. Allison Barto, program director at Boulder, Colorado-based Ball Aerospace, said the company will “complete production, integration and test of the WSF-M satellite in 2023 for shipment to the launch site.”

Charlotte Gerhart, chief of SMC’s Production Corps Low Earth Orbit Division, said WSF-M is projected to launch in late 2023 and become operational in mid-2024. She said SMC plans to order a second WSF-M satellite from Ball Aerospace in 2023 or 2024, with a goal to launch it in 2028.

The heart of the 1,200-kilogram WSF-M is a microwave imager instrument developed by Ball. This sensor collects data used to characterize and measure ocean surface vector winds, tropical cyclone intensity, soil moisture, snow depth and sea ice. WSF-M also will carry a government-furnished space weather payload developed by the Air Force Research Laboratory and intended for inclusion on both WSF-M satellites.

Cory Springer, director of weather and environment at Ball Aerospace, said WSF-M does not include the atmospheric sounding capability of DMSP’s microwave instrument. He said DoD identified ocean surface vector winds and tropical cyclone intensity as the highest priorities, and removed the sounding requirement from WSF-M as that capability could be accomplished by other means such as hosted payloads on other platforms.

Over the past two years Ball Aerospace has conducted studies for SMC and NOAA to look at possible options to deploy compact microwave sounders, and no decisions have been made, said Springer.

He noted that DMSP satellites are able to make measurements of ocean surface wind speeds, but not direction, while WSF-M provides both speed and direction information.

EO/IR WEATHER SYSTEM

The current effort to replace DMSP’s cloud-characterizing electro-optical and infrared (EO/IR) capabilities with new satellites started in 2017 when the Air Force issued a solicitation for ideas from industry. In 2018, the same year that the Air Force canceled ORS-8, the EO/IR effort was turned over to SMC’s newly formed Space Enterprise Consortium (SpEC), an organization created to attract startups and small businesses by utilizing so-called Other Transaction Authority agreements intended to reduce red tape and allow contractors to co-invest in projects.

In June 2020, the Space Enterprise Consortium awarded $309 million in contracts to three companies — Raytheon Technologies, General Atomics, and Atmospheric & Space Technology Research Associates — to develop prototypes for their competing visions of an operational EO/ IR Weather System (EWS) constellation.

SMC is currently evaluating the three proposed EWS concepts and plans to select at least one for an on-orbit demonstration in 2023. The Space Force, in the budget request it sent Congress early last year, said it expects to field operational EWS satellites in mid-2026.

Raytheon says it can leverage its expertise building sensors for NOAA’s JPSS satellites to quickly field an EWS concept it calls TWICC (short for Theater Weather Imaging and Cloud Characterization).

Shawn Cochran, head of Raytheon’s civil and environmental space programs, said TWICC would carry a smaller version of the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) instrument originally developed under NPOESS, currently flying on NOAA’s Suomi NPP and JPSS-1 satellites, and installed on the JPSS-2 satellite launching next year.

Cochran said Raytheon’s instrument will be integrated into a small satellite bus suitable for launching as a secondary payload on one of the Space Force’s workhorse rockets, such as SpaceX’s Falcon 9 or United Launch Alliance’s Atlas 5. Cochran declined for competitive reasons to be more specific about TWICC’s size or how many of the satellites would be needed to replace the coverage provided by DMSP. Raytheon also declined to identify other members of its team.

General Atomics Electromagnetic Systems, meanwhile, is proposing a system of 15 satellites about 200 kilograms in size. The company announced the completion of the initial design review April 29 and said it was “on track to deliver a prototype EWS system by 2022 capable of filling the gaps in critical weather data for the U.S. military as the DMSP approaches the end of its lifecycle.”

Nick Bucci, vice president of General Atomics’ missile defense and space systems unit, said the company’s EWS spacecraft will fly a visible and infrared instrument from EOVista, a supplier of imaging sensors for airborne platforms. Braxton, a company now owned by Parsons Corp., is developing a ground system architecture for command and control of the EO/IR satellites.

Atmospheric & Space Technology Research Associates (which goes by ASTRA and is unrelated to rocket startup Astra) is offering a roughly 50-satellite constellation of 12U cubesats. The Louisville, Colorado-based company’s team includes Lockheed Martin, Science and Technology Corp., Pumpkin Inc., and Atmospheric & Environmental Research.

“We’re leveraging a lot of technologies that are readily available,” ASTRA’s chief operating officer Chad Fish said. The company estimates it will take about 200 cubesats to operate the system for 15 years.

Fish noted that cubesats cannot accommodate large imaging instruments like VIIRS but there are now cheaper alternatives that can be deployed in larger numbers. “That is part of the trade off of a lower cost proliferated constellation,” he said. “VIIRS is a very elegant solution that has taken decades to develop. The technology that we’re providing does many of the same things, maybe in slightly different ways.”

Regardless of which company’s concept Space Force chooses, the operational EWS satellites will be expected to take over DMSP’s coverage of the early-morning orbit.

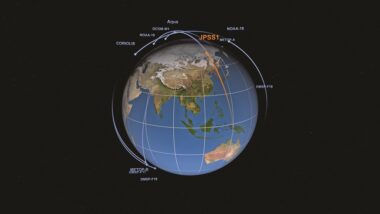

Responsibility for keeping this key weather-observing orbit covered was assigned to the Defense Department under a post-NPOESS pact that made NOAA responsible for the afternoon orbit and extended a plan to rely on Eumetsat for coverage of the mid-morning orbit.

Polar orbiting satellites like DMSP, JPSS and Eumetsat’s Metop series fly in sun-synchronous orbits synchronized with the Earth’s rotation so that a given satellite crosses the equator at the same local time each day. Under NPOESS, the United States originally planned to cover all three key orbits on its own. When it restructured the program in 2006 to rein in costs, it cut six planned NPOESS satellites to four and agreed to rely on Eumetsat for the mid-morning orbit.

Raytheon, General Atomics and ASTRA all said their proposed solutions would enable Space Force to fulfill the military’s commitment to its civilian partners to keep the early-morning orbit covered.

In addition, NOAA could send small weather sensors into the early morning orbit through a demonstration program called SounderSat. If that program is approved this year and given funding, the agency could begin acquiring data with small satellites in the mid-2020s.

Time, however, remains of the essence — a point not lost on DoD’s civilian partners. DMSP and NOAA’s last-generation POES satellites are going to be dying off, said Greg Mandt, NOAA Joint Polar Satellite System program director.

CONGRESSIONAL CONCERNS

In the wake of NPOESS, DoD’s weather satellite plans came under intense congressional scrutiny and continue to be closely watched. “For a decade, the Air Force has been under the gun about how to fill these weather gaps,” said Tierney, the former congressional staffer.

A turning point came two years ago when the Government Accountability Office took weather satellites off its list of “high risk” defense programs. In a March 2019 report, the congressional watchdog agency said it was removing weather satellites from the high-risk list “because with strong congressional support and oversight, NOAA and DoD have made significant progress since 2017 in establishing and implementing plans to mitigate potential gaps in weather satellite data.”

Despite GAO’s positive 2019 assessment, the House Appropriations Committee later that same year added language to the 2020 defense spending bill expressing “concerns about the Air Force’s weather acquisition strategy and commitment to provide accurate and timely weather data, a mission with a profound impact on daily worldwide military operations.”

The bill directed the Air Force to submit a report to its congressional overseers with proposed acquisition plans, cost estimates and schedules for military weather satellites. That report was delivered to Capitol Hill last fall, according to SMC.

In late December, Congress fully funded DoD’s weather satellite budget request for 2021 but admonished the Space Force — established just the year before to take over the Air Force’s space responsibilities — to keep a close eye on the ongoing procurements.

Specifically, Congress provided $131 million for the EWS program, $86 million for WSF-M, and $36 million for weather-related research and development.

Congress also inserted $10 million not requested by the Pentagon for the Space Force to continue to assess options for using commercial weather data to meet military needs. The money arrived as SpaceX was finishing a $2 million study contract SMC awarded in July 2020 to, as Gerhart put it, “assess the feasibility and long-term viability of a weather data as-a-service business model.”

Gerhart said SpaceX completed the study in March but declined to discuss its findings. SpaceX did not respond to requests for comment.

Buying commercial weather services is a possibility in the future, Gerhart said, if companies are able to offer what DoD needs. At the moment, that’s a big if. “There’s not a lot of commercial data at this point,” she said. “There is no EO/IR commercial data available, or commercially available microwave data.”

Meanwhile, the funding forecast for the WSF-M and EWS satellites remains partly cloudy. While the Biden administration has yet to submit its detailed Space Force funding request to Congress, five-year budget projections the Pentagon submitted early last year showed $750 million in total funding for EWS between 2018 and 2025. The funding would ramp up from $131 million in 2021 to $174 million in 2022 before steadily declining in 2023, 2024 and 2025 — the years when the EWS program expects to launch at least one prototype and start building the operational versions it wants to field in 2026.

Funding for WSF-M, which totaled nearly $210 million in 2020 before falling to $86 million for 2021, was projected to fall sharply in 2022, 2023, 2024, and 2025 — the period during which Space Force is planning to place its order for a second WSF-M satellite that would launch in 2028.

Tierney said the fact that DoD in 2021 got all the weather satellite money it requested is a sign that Congress is ready to wipe the slate clean and give the Space Force a chance to execute these programs. Likewise, last year’s five-year budget projections aside, Congress appropriates on a year-to-year basis and is still waiting to see how much money the Space Force ends up requesting for EWS and WSF-M for 2022.

Budget matters aside, Gerhart said SMC is confident it can deploy new weather satellites before the last of the DMSPs are lost to old age, but acknowledges “there certainly is risk.”

“There could be a gap in capability if DMSP satellites all failed before we get WSF-M and EO/IR EWS on orbit,” said Gerhart. “How significant is the risk? We can’t quantify that.”

Indeed, with the most recent DMSP health assessment concluding that the remaining satellites have perhaps another four or five years of service at best, Gerhart said SMC’s focus is on getting WSF-M and the first EWS satellites in orbit. “Those are real programs, real capabilities with real budgets.”

This article originally appeared in the May 2021 issue of SpaceNews magazine.