The RB team, together with experts in material science, robotics, and aerospace engineering submitted an idea that was granted €100k to develop a preliminary proof of concept.

The proposed approach focuses on the lab's specialty—robotic building—and has four main components—digging out the regolith, printing a new habitat using an additive manufacturing process, coordinating the work between all the robots that would be needed to complete the tasks, and powering them as well as the habitat.

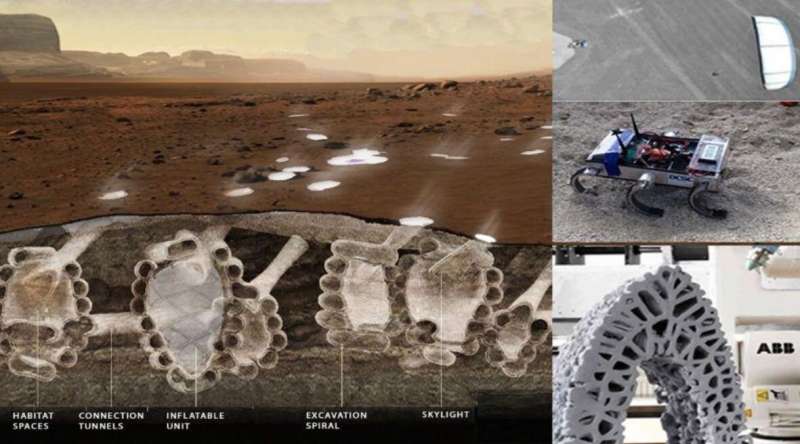

Excavating regolith with robots has been explored previously, but usually in the context of the moon. Different patterns of excavation are useful for building different structures, and the pattern the RB team focused on was a downwards sloping spiral. Such a structure could create a stable, safe structure within a relatively small footprint on the surface.

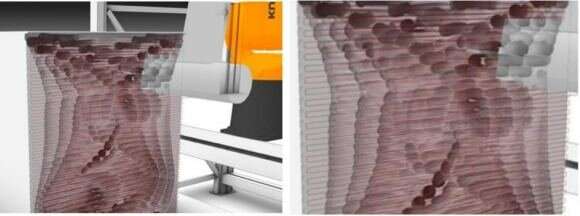

Modeling the stresses and strains on that structure is a key component of the current study project. The team developed a 1m x 1m scale prototype of a fragment with patterns that would allow them to create safe and stable areas effectively. Some of those areas were designed with habitation in mind, including detachable plant areas that could house hydroponically grown plants.

Tons upon tons of regolith would have to be removed from any real-life scale excavation site. That regolith is used as material to 3D print a stable habitat. Originally, the team was planning on combining regolith with liquid Sulfur to produce concrete. But after involving material scientists and an industrial partner specialized in robotic printing with cement they settled on using cement-based concrete by tapping into some of Mars' water resources. Creating cement itself requires an infrastructure though, so any such plan to use regolith would have to wait until after that infrastructure was already in place on the planet.

Structuring the habitat itself is also a key consideration when designing what shape should be 3D printed. The team focused on relatively porous structures, which allowed them to use less material in its construction. However, the structures still had remarkably high strength and durability and also provided good insulation from the radiation and micrometeorite impacts the subsurface colony is looking to avoid.

Some of the advantages of this approach are due to one of the biggest drivers of innovation—collaboration. The project is coordinated by the RB lab but involves partners both at TUD and external commercial partners. These collaborators bring civil, aerospace, and robotic engineering expertise, and additive manufacturing technologies for developing the robotic swarm construction approach .