And late last year, China concluded a successful lunar mission that returned soil samples to Earth for the first time in 44 years. Unfortunately, Beijing’s ambitions in space are the same as they are on Earth: to establish itself as hegemon.

In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping called for China to pursue a “space dream” to transform China into a world-leading space power by 2045. But Ye Peijian, head of the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program, disclosed the imperial aspirations of China’s activities in space.

“The universe,” he said, “is an ocean, the moon is the Diaoyu Island [Senkaku Islands, claimed by Japan], Mars is the Huangyan Island [Scarborough Shoal, claimed by the Philippines]. If we don’t go when we can go now, then future generations will blame us. If others go, then they will take over, and you won’t be able to go even if you wanted to. This is reason enough.”

In other words, China will follow a policy of might-makes-right in the solar system to bend the world to Beijing’s will, similar to how it has ignored international law, bullied competition, deployed weapons, and employed force to establish de facto control of the South China Seas.

Space offers a plethora of strategic resources in the form of energy, materials, and real estate to accelerate economic growth. For example, space-based solar power promises to deliver unlimited clean energy. Lunar minerals can serve to bootstrap space industries, while water locked up in the lunar poles may turn the moon into an interplanetary gas station. Mars provides roughly the same amount of dry land as Earth, a blank canvas for future development.

A country that secures exclusive control of any of these space resources may dominate terrestrial geopolitics through new wealth and instruments of power.

Existing international law prohibits national-level seizure of space resources. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST), ratified by 111 countries, including the United States, Russia, and China, governs the exploration and use of outer space. Article II affirms that no country can claim sovereignty over the moon or other celestial bodies, though they are free to utilize their resources, a policy that the United States codified into law to guide space entrepreneurs.

Beijing may explicitly claim the moon or Mars, in flagrant violation of the OST. Such a claim would resemble its claims in the South China Sea, which the Permanent Court of Arbitration, an intergovernmental tribunal to resolve disputes of member states, found to have no legal basis in established international law. Alternatively, Beijing may claim to adhere to the OST while doing the opposite and defying the international rules-based order.

To secure control of space, China could send commercial space vehicles to lay claim to valuable space resources, similar to how, in March of this year, Beijing anchored a 220-ship armada outside a disputed reef in an attempt to solidify its national claim. Or China might simply plunder resources such as lunar ice with complete disregard for other stakeholders. China may also take a militaristic route and employ its growing arsenal of ground-based and space-based counter-space weapons to secure a dominant position in space and order others to keep out.

Regardless of the form it takes, a future in which Beijing dominates outer space is not a future that will lead to the benefit of all mankind, much less one that secures U.S. interests.

Fortunately, the United States can still stop Beijing from seizing exclusive control over space resources if Washington takes action now.

First and foremost, America must recognize Beijing’s imperialistic space ambitions and prevent China from gaining dominance. Space technology takes a long time to move from idea to orbit, and Beijing is used to playing a much longer game than Washington.

To counter Beijing, the United States needs a steady space vision to guide policy for commercial, civil, and military space applications across election cycles. The National Space Council is ideally suited to work with industry, academia, and Washington to implement a positive vision of outer space utilization while also deterring China’s ambitions in space. Going forward, the council should proffer a bipartisan space vision and policy recommendations that secure long-term American interests in space.

There is certainly life on #Mars! We’re the life of the party! #Zhurong #Tianwen1 #CNSA @CNSA_en pic.twitter.com/cC8pZVmyVt

— China National Space Administration (CNSA) (@CNSA_en) May 15, 2021

Additionally, the United States can harness the potential of friendly rising space powers to establish a favorable balance of power in space while also cementing rules and norms.

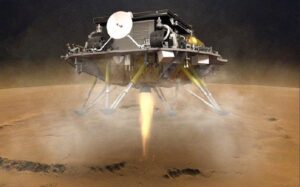

The day before China’s rover arrived in orbit around Mars, a UAE satellite also arrived at Mars to study Martian weather. (China’s rover will remain in orbit until sometime this month as it searches for a suitable landing site; the Emirati satellite will not land on the surface of Mars.) The UAE space program aims to generate wealth in a post-oil economy and has plans to found the first inhabitable settlement on Mars by 2117.

India also has a flourishing space program and is making a play to become a major space power. India actually beat China to the moon and nearly set a world-first in an attempted landing at the lunar south pole in 2019. India also has a strong indigenous commercial space community that has launched over 300 satellites from 33 countries over the last 20 years.

Through partnerships and scientific collaboration, the United States should encourage the growth of UAE and Indian space programs – as well as the programs of traditional allies such as Japan and the European Space Agency – as a hedge against Chinese ambitions in space. In so doing, the United States must take prudent steps to ensure allied space programs are aligned with American interests and adhere to international norms and law.

Back at home, U.S. decision makers must continue to foster the growth of commercial space. America’s future in space depends on innovative startups with fresh ideas that can translate difficult technical challenges into marketable products. NASA is demonstrating a way to foster startups with its Commercial Lunar Payload Services program, which pays vendors to deliver NASA payloads to the lunar surface. Thus far, over 14 vendors, mostly startups, are on contract. Similarly, the Space Force is seeking to introduce commercial capabilities into all of its mission areas to better integrate new ideas and establish a broader industrial base.

Washington does not need to dominate space but instead needs to prevent Beijing from realizing its troubling zero-sum ambitions to control space resources and become a space-power hegemon. To foil Beijing, the United States and its allies need to prevent China from securing a technological or military advantage in space. And if necessary, the United States must be prepared to use economic and military tools to keep Beijing in check.

The moon and Mars are not disputed islands, nor should they become one. Beijing’s revisionist agenda must not leave Earth.

Maj. Jared Thompson is a U.S. Air Force officer and visiting military analyst at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), where he contributes to FDD’s Center on Military and Political Power. FDD is a Washington-based, nonpartisan research institute focusing on national security and foreign policy. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Defense Department or the U.S. Air Force.