"With a sufficiently large radio telescope off Earth, we could track the processes that would lead to the formation of the first stars, maybe even find clues to the nature of dark matter."

Radio telescopes on Earth can't probe this mysterious period because the long-wavelength radio waves from that time are reflected by a layer of ions and electrons at the top of our atmosphere, a region called the ionosphere. Random radio emissions from our noisy civilization can interfere with radio astronomy as well, drowning out the faintest signals.

But on the Moon's far side, there's no atmosphere to reflect these signals, and the Moon itself would block Earth's radio chatter. The lunar far side could be prime real estate to carry out unprecedented studies of the early universe.

"Radio telescopes on Earth cannot see cosmic radio waves at about 33 feet [10 meters] or longer because of our ionosphere, so there's a whole region of the universe that we simply cannot see," said Saptarshi Bandyopadhyay, a robotics technologist at JPL and the lead researcher on the LCRT project. "But previous ideas of building a radio antenna on the Moon have been very resource intensive and complicated, so we were compelled to come up with something different."

Building Telescopes With Robots

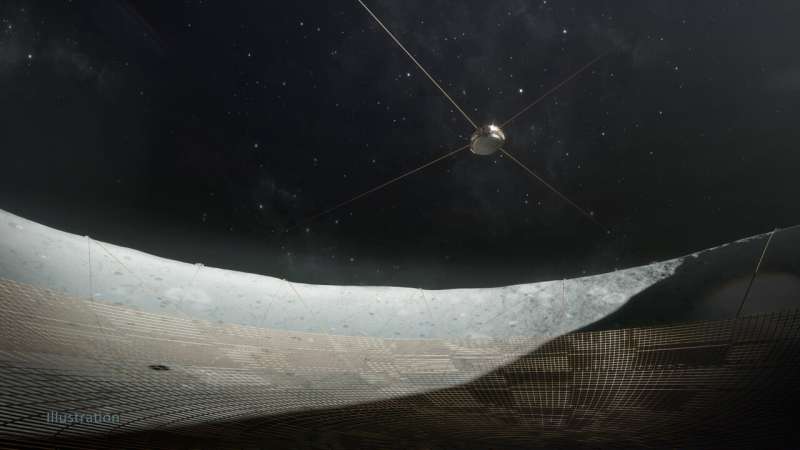

To be sensitive to long radio wavelengths, the LCRT would need to be huge. The idea is to create an antenna over half-a-mile (1 kilometer) wide in a crater over 2 miles (3 kilometers) wide. The biggest single-dish radio telescopes on Earth—like the 1,600-foot (500-meter) Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) in China and the now-inoperative 1,000-foot-wide (305-meter-wide) Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico—were built inside natural bowl-like depressions in the landscape to provide a support structure.

This class of radio telescope uses thousands of reflecting panels suspended inside the depression to make the entire dish's surface reflective to radio waves. The receiver then hangs via a system of cables at a focal point over the dish, anchored by towers at the dish's perimeter, to measure the radio waves bouncing off the curved surface below. But despite its size and complexity, even FAST is not sensitive to radio wavelengths longer than about 14 feet (4.3 meters).

With his team of engineers, roboticists, and scientists at JPL, Bandyopadhyay condensed this class of radio telescope down to its most basic form. Their concept eliminates the need to transport prohibitively heavy material to the Moon and utilizes robots to automate the construction process. Instead of using thousands of reflective panels to focus incoming radio waves, the LCRT would be made of thin wire mesh in the center of the crater. One spacecraft would deliver the mesh, and a separate lander would deposit DuAxel rovers to build the dish over several days or weeks.

DuAxel, a robotic concept being developed at JPL, is composed of two single-axle rovers (called Axel) that can undock from each other but stay connected via a tether. One half would act as an anchor at the rim of the crater as the other rappels down to do the building.

"DuAxel solves many of the problems associated with suspending such a large antenna inside a lunar crater," said Patrick Mcgarey, also a robotics technologist at JPL and a team member of the LCRT and DuAxel projects. "Individual Axel rovers can drive into the crater while tethered, connect to the wires, apply tension, and lift the wires to suspend the antenna."

Identifying Challenges

For the team to take the project to the next level, they'll use NIAC Phase II funding to refine the capabilities of the telescope and the various mission approaches while identifying the challenges along the way.

One of the team's biggest challenges during this phase is the design of the wire mesh. To maintain its parabolic shape and precise spacing between the wires, the mesh must be both strong and flexible, yet lightweight enough to be transported. The mesh must also be able to withstand the wild temperature changes on the Moon's surface—from as low as minus 280 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 173 degrees Celsius) to as high as 260 degrees Fahrenheit (127 degrees Celsius) – without warping or failing.

Another challenge is to identify whether the DuAxel rovers should be fully automated or involve a human operator in the decision-making process. Might the construction DuAxels also be complemented by other construction techniques? Firing harpoons into the lunar surface, for example, may better anchor the LCRT's mesh, requiring fewer robots.

Also, while the lunar far side is "radio quiet" for now, that may change in the future. China's space agency currently has a mission exploring the lunar far side, after all, and further development of the lunar surface could impact possible radio astronomy projects.

For the next two years, the LCRT team will work to identify other challenges and questions as well. Should they be successful, they may be selected for further development, an iterative process that inspires Bandyopadhyay.

"The development of this concept could produce some significant breakthroughs along the way, particularly for deployment technologies and the use of robots to build gigantic structures off Earth," he said. "I'm proud to be working with this diverse team of experts who inspire the world to think of big ideas that can make groundbreaking discoveries about the universe we live in."