As the importance of ESG grows, the space industry will become an increasingly critical part of how every company operates.

The momentum has been accelerating after BlackRock, the world’s largest fund manager overseeing roughly $9 trillion of assets, said last year it would base all its decisions on ESG criteria.

“Climate risk is investment risk,” BlackRock chief executive officer Larry Fink wrote in his annual letter to other CEOs.

The concept got a major push when Allison Lee, acting chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), outlined plans March 15 to put ESG at the heart of the U.S. financial market regulator’s agenda.

Setting the stage for potentially forcing companies to monitor and disclose ESG targets, she said: “I am asking the staff to evaluate our disclosure rules with an eye toward facilitating the disclosure of consistent, comparable, and reliable information on climate change.”

It joins similar efforts in Europe and elsewhere as measures to tackle climate change get a significant boost from the U.S. rejoining the Paris Agreement, which aims to drive global action on the issue.

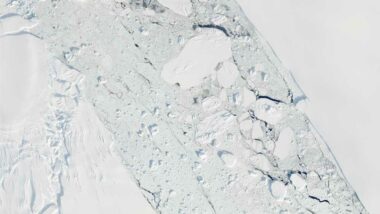

A lot of ESG data about the Earth can only be gained from the vantage point of satellites beyond it, putting space in the center of this international trend.

MARKET DEMAND

Space likely has the biggest role to play in the environmental side of ESG, one of its most visible components, and where satellite companies are already helping companies track and meet climate change targets.

“Nature will be on the balance sheet, which means space will be on the balance sheet because you can’t see ESG without us,” said Andrew Zolli, vice president of impact initiatives for U.S. satellite imagery operator Planet.

Many space companies, ranging from satellite operators to dedicated analytical businesses, have been growing in recent years as ESG trends expand their market to businesses that have not sought space capabilities before.

Underpinning much of the demand are the financial crises, corporate governance scandals and environmental declines over the last decade, according to Ursa Space Systems’ Daniel Baruch.

They have helped deteriorate shareholder value and trust in companies, said Baruch, director of global energy markets and business development at U.S.-based Ursa, a geospatial analytics company specializing in applications for synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data.

“But you’re also seeing an influx in just the availability of data to provide this transparency,” he said.

“You’re seeing more sustainability information and different data sets that are coming out, exponentially in the last three years.”

More businesses realize they need to measure their carbon emissions and other impacts on climate, Cooper Elsworth, sustainability product manager at Californian geospatial analysis firm Descartes Labs, noted.

On the flip side, it is also becoming increasingly important for companies to assess the changing climate’s impact on their operations, including physical and production risks.

“Remote sensing provides a scalable, low-friction data source to begin to quantify these climate and decarbonization risks on businesses,” Elsworth said.

“The adage ‘if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it’ is particularly relevant to climate action and ESG reporting right now — a compelling reason for the space sector to become involved in this burgeoning ESG landscape.”

Descartes Labs primarily focuses on using remotely sensed data to improve carbon accounting and carbon reduction measures for corporations.

It works with businesses with supply chains that have liability associated with tropical deforestation, for example, helping them monitor, attribute, and reduce their impact on the levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

TARGETING POLLUTERS

Canada-based GHGSat uses its satellites to monitor greenhouse gas emissions from industrial facilities around the world.

While space agencies including NASA and ESA have been monitoring these gases for years to inform global climate change models, GHGSat’s satellites focus on a more granular level to track facilities with much lower emission rates.

“What we’ve wanted to do from the get-go was to measure emissions from targeted individual facilities, and work with the operators with those facilities to understand, control and reduce their emissions,” CEO Stephane Germain said.

The company combines its measurements with third-party data, providing analysis to the emission generators themselves, regulators and market analysts.

At the top of the list of customers for GHGSat are those in the oil & gas market — the largest industrial source of emissions worldwide.

GHGSat also has customers across the next most prominent sources of emissions: power generation, coal mining, agriculture and waste management.

“We’ve done some exploratory discussions with several large … consumer-facing customers, and they have a clear interest in understanding the greenhouse gas intensity of their supply chains,” Germain added.

He underlined growing interest in understanding the climate impact of steel and aluminum production, and how suppliers differ when comparing tons of greenhouse gases per unit of material.

“That’s a very exciting area … it’s another way to put a value to the carbon intensity of a commodity that is being used by large consumer-facing companies, and we’re certainly active in that analysis,” Germain said.

Coal-fired mills make much of the world’s steel, especially in some developing countries, producing significantly higher emissions than a company using hydroelectric energy for their power.

GHGSat has three in-orbit nanosatellites and another eight it intends to launch by the end of 2022 to meet growing demand.

ANOTHER GREEN PUSH

“The incorporation of ESG into operational demands is absolutely rising,” said Peter Platzer, CEO of U.S.-based space data and analytics provider Spire Global, which has launched more than 100 tiny satellites in the past decade to track airplanes, ships and weather.

“It’s rising because of changes in regulatory environments, changes in customer behavior and changes in policy,” Platzer said.

“And given that it is a global problem, or global demand, satellite data is going to be absolutely crucial for companies to answer those three-pronged [ESG] changes.”

One way a company can get a handle on ESG is by creating a “digital twin,” a virtual copy of its business that can simulate various changes.

Spire’s analysis and weather forecasting capabilities enable shipping companies, for instance, to plot more efficient routes to save fuel costs. It has the dual benefit of helping them meet increasingly stringent emission standards from the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the United Nations agency that sets standards for seafarers.

“If you extend that you will have a digital twin of Earth, which allows you to really understand how the various resources and environmental effects interplay with each other,” he said.

“And again, you cannot do an interplay on a global scale without truly global data — and that means satellites.”

REACHING SUSTAINABILITY

Increasing demand for sustainable products is also driving companies worldwide, including major consumer packaged goods businesses, to make significant changes with where and how they source materials.

Orbital Insight, another geospatial analytics firm based in California, last year announced a pilot project with Unilever, the consumer giant behind Dove, Ben & Jerry’s and many other household products that rely on palm oil.

The project aims to track Unilever’s palm oil supply chain to prevent deforestation.

“By tracing the relationships among farms, mills, refineries and ports, companies can see into the elusive ‘first mile’ of supply chains to identify potential issues,” Orbital Insight product manager Zac Yang said.

“This project is setting the precedent for other consumer packaged goods companies to get farm-level traceability and prevent deforestation through AI with location data, satellite imagery and computer vision. We believe that this will be the future of supply chain monitoring and offers a new level of sophistication for traceability.”

Yang said the company is also receiving interest to extend the technology to cacao, soy, paper and other commodities.

“Our customers are also using the technology outside agriculture, to understand industry and competitor supply chains, as the AI algorithms can be applied to any industry needing insight into where materials within their supply chain are sourced from,” he added.

While the environmental part of ESG is a natural fit for space capabilities, Planet’s Zolli highlighted how it also provides important clues for the other two parts of the acronym.

“We can determine by watching the Earth various things — especially when combining Earth observation data with other data — about how people are being treated,” he said.

Combined with reports on the ground, Zolli pointed to how satellites gain insights into issues including human trafficking, slavery and illegal fishing.

HURDLES TO CLEAR

More work is needed to get a clearer picture of “asset level” information, according to Zolli, such as for knowing precisely who owns what plantation or palm oil concession around the world.

“We can tell you exactly what’s going on there but we can’t always tell you exactly who is responsible,” he said.

“So there’s a lot of work to do in the middle to bring this vision about.”

One of the other biggest challenges facing the industry is the lack of ESG regulations, standards and universally recognized guidelines.

Two of the most influential ESG data standards are the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), a San Francisco nonprofit that publishes a comprehensive list of industry-specific factors, and another led by the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation (IFRS), backed by the International Federation of Accountants in Geneva.

A dizzying array of competing standards makes guidelines and comparisons challenging, and is an issue that the SEC and other regulatory bodies are moving to address.

In the meantime, Baruch said the space industry has an opportunity to “provide markets with more timely asset-level monitoring, rather than relying on annual, self-reported public disclosures from companies that may not necessarily be accurate [or] objective.”

However, ESG is still “mostly a rich person’s acronym,” Platzer added.

It is unclear how countries such as India, with more than a billion people and relatively lax environmental regulations, will adopt the movement.

That said, Platzer believes climate change poses a generational challenge for humanity.

He sees space as paramount for hitting Net Zero, the concept of taking as much carbon from the atmosphere as that going in to address climate change.

“Data from the ultimate vantage point will become more and more relevant, to more and more people, because of climate change and the flip-side of climate change which is ESG and Net Zero,” he said.

This article originally appeared in the April 19, 2021 issue of SpaceNews magazine.