The company said last August its modular approach for small satellite buses ranging from 12 to 35 kilograms helped triple revenues over the previous 12 months.

After expanding from 30 people to more than 100 since moving from cubesats to larger nanosatellite-class spacecraft around 2017, Buzas has high hopes for its larger and more capable MP42 bus.

“It will enable a large number of organisations to enter and benefit from the space market previously prevented by barriers in the microsat segment such as cost, lack of modularity, mechanical restraints and suitable mission operations,” Buzas said in a published statement.

“Their high-end applications and mega constellation requirements can mostly be carried out with a payload weight of 40kg and above, and I see a big opportunity for lowering cost and lead time reduction in this segment, too.”

Buzas told SpaceNews in an interview that it is already building MP42 prototypes to meet demand from existing and new customers, and a launch is planned for the middle of next year.

NanoAvionics has developed satellites for companies including British Earth observation venture Sen and Tysons, Virginia-based Omnispace, which is building a network to keep trackers, sensors and other smart devices on the ground constantly connected.

It also supplies components to AST & Science, which last year said it will raise $462 million to fund its cellphone-compatible satellite constellation by going public through a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC).

AST & Science acquired a controlling interest in NanoAvionics two years ago, and Buzas said its move into heavier satellites could see it play a bigger role in its upcoming constellation.

Going large

With larger buses, Buzas said engineers could focus their creativity on improving accuracy and onboard resources, including deployable panels and antennas — rather than on how to “squeeze everything into a small box.”

“Your hands suddenly become untied,” he said.

Primarily because of how expensive it used to be to launch satellites per kilogram, he believes the nanosatellite market has been too preoccupied with size and weight.

“Miniaturization on its own means nothing,” Buzas contends, pointing to how small consumer cellphones became before a trend toward larger screens and longer battery lives took over.

“There were models where you had to press buttons almost with a matchstick,” he noted.

Buzas said increasingly affordable launch services, and the proliferation of rideshare missions, will help shift industry focus away from the smaller end of the small satellite market.

However, moving into larger microsatellites will see NanoAvionics compete more head-on with established manufacturers, including Airbus-owned Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd. (SSTL) and Raytheon-owned Blue Canyon Technologies.

Buzas believes there is plenty of room in the market, pointing to forecasts predicting 10,000 small satellites will be launched over the next 10 years.

NanoAvionics will also continue to produce buses for the nanosatellite sector, which Buzas said will continue to grow for niche applications.

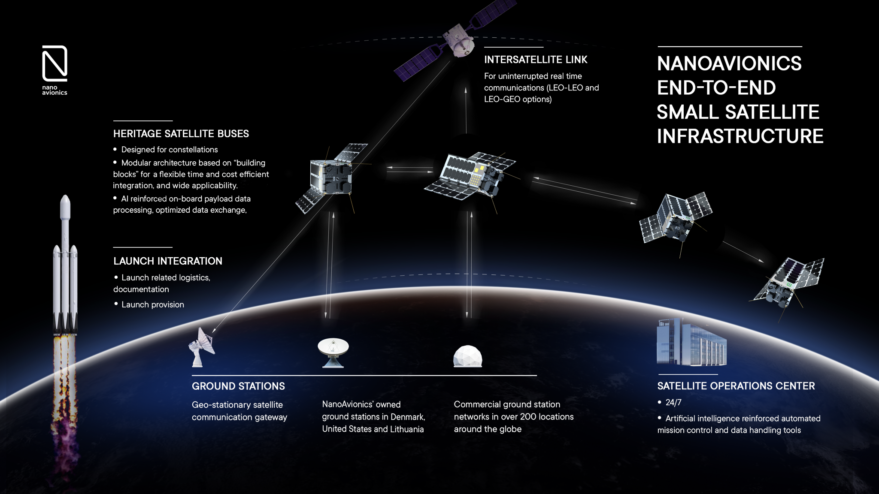

The company, which also facilitates rideshare launches with its end-to-end service offering, expects to produce about 120 satellites per year by 2025.