Magnetometers register changes in the Earth's magnetic field. When charged particles from our Sun bombard the Earth's magnetic field, it stores up energy like a battery. Eventually, this energy is released leading to large-scale electrical currents in the ionosphere which generate disturbances of magnetic fields on the ground. At extremes, this can disrupt power lines, electronic and communications systems and technologies such as GPS.

Using historical data from the SuperMAG collaboration of magnetometers, the researchers applied algorithms from network science to find correlations between magnetometer signals during 41 known substorms that occurred between 1997-2001. These use the same principles that allow a social networking site to recommend new friends, or to push relevant advertisements to you as you browse the internet.

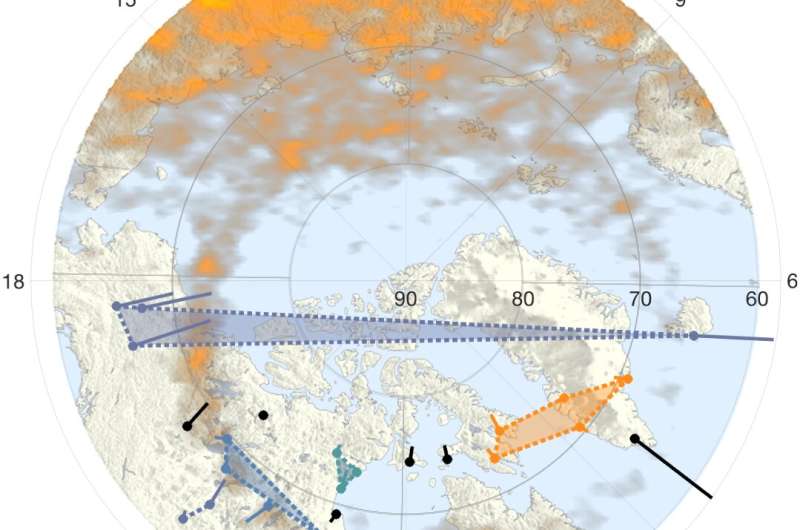

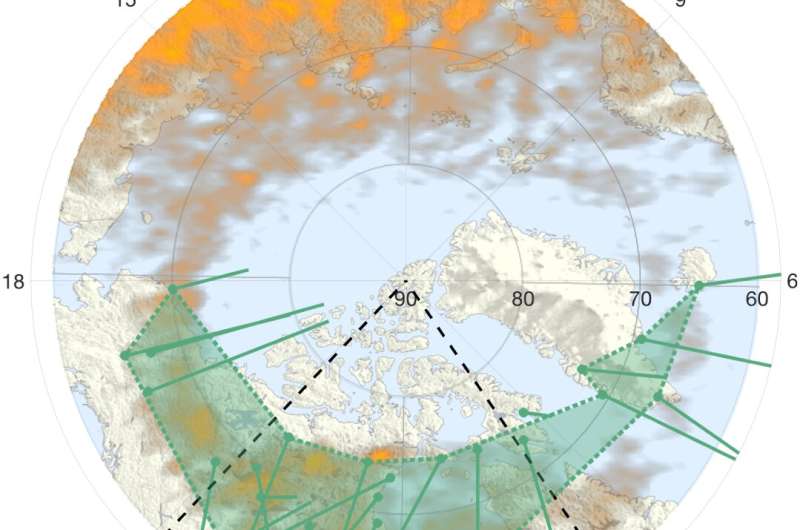

Magnetometers detecting coherent signals were linked into communities, regardless of where they were located on the globe. As time progressed, they saw each substorm develop from many smaller communities into a single large correlated system or community at its peak. This led the authors to conclude that substorms are one coherent current system which extends over most of the nightside high latitude globe, rather than a number of individual small and disjointed current systems.

Dr. Lauren Orr, who led the research as part of her Ph.D. at the University of Warwick Department of Physics and is now based at Lancaster University, said: "We used a well-established method within network science called community detection and applied it to a space weather problem. The idea is that if you have lots of little subgroups within a big group, it can pick out the subgroups.

"We applied this to space weather to pick out groups within magnetometer stations on the Earth. From that, we were trying to find out whether there was one large current system or lots of separate individual current systems.

"This is a good way of letting the data tell us what's going on, instead of trying to fit observations to what we think is occurring."

Some recent work has suggested that auroral substorms are composed of a number of smaller electrical current systems and remain so throughout their lifecycle. This new research demonstrates that while the substorm begins as lots of smaller disturbances, it quite rapidly becomes a large system over the course of around ten minutes. The lack of correlation in its early stages may also suggest that there is no single mechanism at play in how these substorms evolve.

The results have implications for models designed to predict space weather. Space weather was included in the UK National Risk Register in 2012 and updated in 2017 with a recommendation for more investment in forecasting.

Co-author Professor Sandra Chapman adds: "Our research introduces a whole new methodology for looking at this data. We've gone from a data poor to a data rich era in space plasma physics and space weather, so we need new tools. It's a first to show that you can take one of these tools to our field and get a really important result out of it. We've had to learn a lot to be able to do that, but in doing so it opens up a new window into the data."