ELSA-d, or End of Life Services by Astroscale-demonstration, comprises a 175-kilogram servicer spaceraft and a 17-kilogram client satellite both set to launch March 20 as part of a GK Launch Services’ Soyuz-2 rideshare mission lifting off from Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan.

The ELSA-d spacecraft will be controlled from the U.K., where Astroscale has built what it touts as the first mission control center dedicated to in-orbit servicing.

The U.K. government provided a £4.2 million ($5.9 million) grant through its U.K. Research and Innovation (UKRI) public body to develop the National In-Orbit Servicing Control Centre located at the Satellite Applications Catapult in Harwell, Oxfordshire, as the country looks to become a leader in the emerging market for orbital debris removal and other in-space services.

U.K. Science Minister Amanda Solloway said the country is already “Europe’s largest investor in helping with space clean-up,” having invested a total €95.5 million in ESA’s Space Safety program.

That funding includes €12 million for the Active Debris Removal and In-Orbit Servicing (ADRIOS) initiative, a separate servicing demonstration program the European Space Agency announced in 2019, as well as €70 million for space weather observation and forecasting.

With funding from ADRIOS, Swiss startup ClearSpace plans to launch a spacecraft in 2025 that will remove a Vega rocket upper stage left in orbit in 2013.

The U.K. government has been focusing on emerging capabilities as it seeks a larger share of the global space industry after Brexit.

Mark Emerton, UKRI’s innovation lead for robotics and artificial intelligence, said becoming a leader in in-orbit servicing serves as a steppingstone toward in-orbit manufacturing dominance.

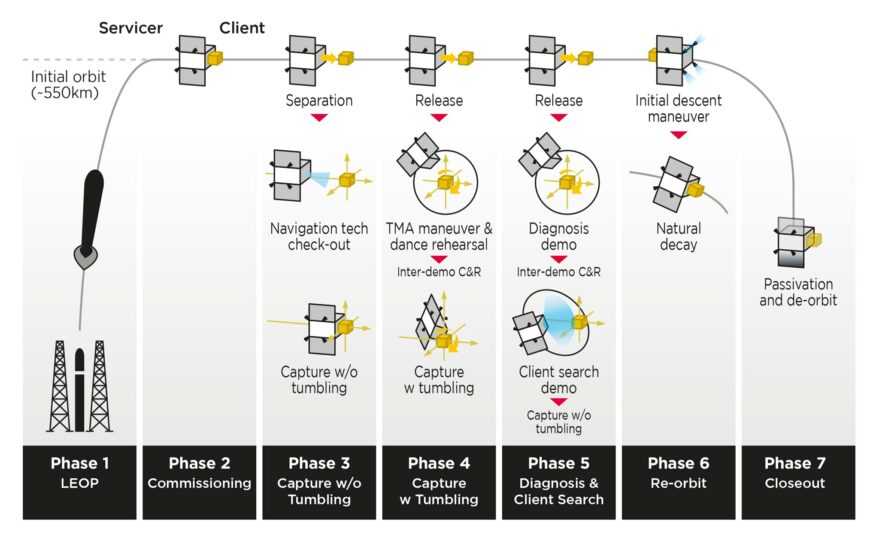

The ELSA-d servicer will demonstrate a number of activities as it maneuvers around its smaller companion satellite, proving capabilities that could be used for other applications.

In orbit, the 175-kilogram servicer — equipped with proximity rendezvous technologies and a magnetic capture mechanism — will repeatedly dock with and release the 17-kilogram client satellite.

“In providing funding support to this demonstrator, we’re helping to support the nascent in-orbit servicing and manufacturing market in general, giving the U.K. a first-mover advantage and attracting further investment and growth,” Emerton said.

Astroscale expects to complete the main demonstration elements of ELSA-d by the end of this year, ahead of a final de-orbiting phase that it expects to last between seven to 10 years.

While that’s roughly how long it would take dead spacecraft the size and shape of ELSA-d to naturally reenter the atmosphere from a 550-kilometer low Earth orbit (LEO), a big part of Astroscale’s value proposition is that it remains in control during the entire de-orbit phase.

John Auburn, managing director of Astroscale UK and group chief commercial officer, said that deorbiting slowly while capturing images and performing collision avoidance as needed ensures “we don’t hit something and create more debris on the way down.”

Auburn said the deorbit phase of future Astroscale missions will be significantly faster than ELSA-d, which will spend a lot of its fuel in the months ahead as it conducts various demos.

“International guidance is 25 years for de-orbit, we’re going for under 10 years for this demonstration mission, but we’re encouraging the whole satellite industry to work towards 5 years,” he added.

OneWeb compatibility

Astroscale is also working on a separate spacecraft called Elsa-m, designed to capture and de-orbit three or four objects in a single mission for a constellation customer.

Currently, Astroscale’s spacecraft can only latch onto satellites with compatible docking plates.

OneWeb, recently acquired by the British government and Indian telecom company Bharti Global, is the only constellation operator known to be putting Astroscale-compatible plates on its satellites.

Strategies for tackling space debris will be on the agenda for the next G-7 summit of world leaders being held in the U.K. this June, according to Alice Bunn, international director of the UK Space Agency.

Auburn said Astroscale is also bidding this year for a Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) contract to de-orbit a discarded upper stage of a rocket, without a docking plate. He said the mission will happen “probably by 2025,” with a spacecraft that will require “some kind of robotic arm.”

JAXA picked Astroscale last year for the first part of the mission, which will see the startup inspect the tumbling upper stage for an appropriate place to dock.

Meanwhile, U.S.-based Northrop Grumman’s MEV-2 satellite servicer is closing in on Intelsat’s in-service 10-02 spacecraft, which it will dock with to extend its operational life.

Northrop Grumman’s MEV-1 servicer successfully attached to the Intelsat-901 satellite that was in graveyard orbit last year, enabling it to resume services.