Now it is up there working like a charm."

Perched atop the rover's mast, SuperCam's 12-pound (5.6-kilogram) sensor head can perform five types of analyses to study Mars' geology and help scientists choose which rocks the rover should sample in its search for signs of ancient microbial life. Since the rover's Feb. 18 touchdown, the mission has been performing health checks on all of its systems and subsystems. Early data from SuperCam tests—including sounds from the Red Planet—have been intriguing.

"The sounds acquired are remarkable quality," says Naomi Murdoch, a research scientist and lecturer at the ISAE-SUPAERO aerospace engineering school in Toulouse. "It's incredible to think that we're going to do science with the first sounds ever recorded on the surface of Mars!"

On March 9, the mission released three SuperCam audio files. Obtained only about 18 hours after landing, when the mast remained stowed on the rover deck, the first file captures the faint sounds of Martian wind.

"I want to extend my sincere thanks and congratulations to our international partners at CNES and the SuperCam team for being a part of this momentous journey with us," said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for science at NASA Headquarters in Washington. "SuperCam truly gives our rover eyes to see promising rock samples and ears to hear what it sounds like when the lasers strike them. This information will be essential when determining which samples to cache and ultimately return to Earth through our groundbreaking Mars Sample Return Campaign, which will be one of the most ambitious feats ever undertaken by humanity."

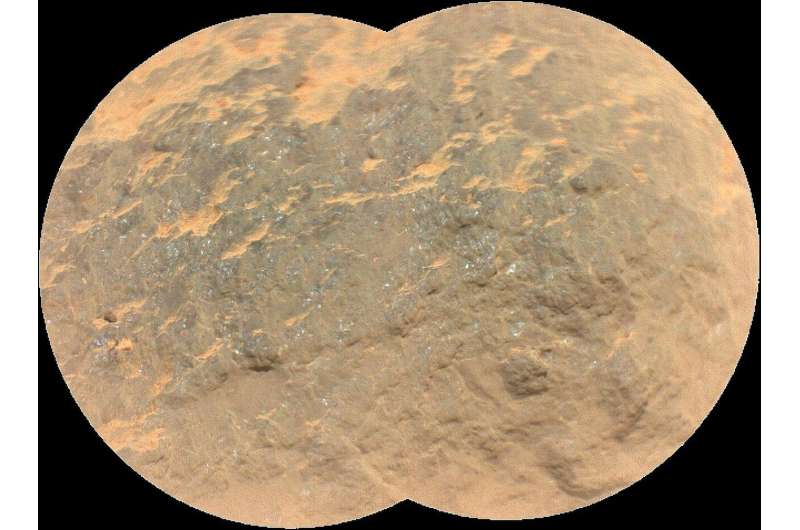

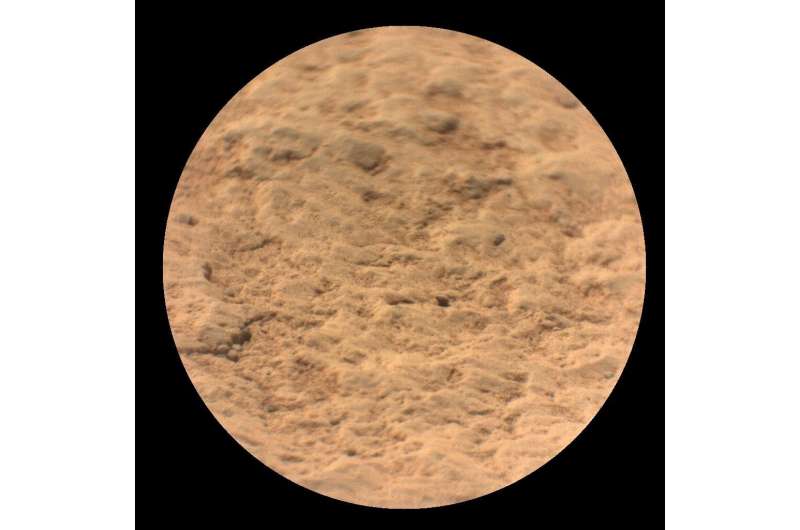

The SuperCam team also received excellent first datasets from the instrument's visible and infrared (VISIR) sensor as well as its Raman spectrometer. VISIR collects light reflected from the Sun to study the mineral content of rocks and sediments. This technique complements the Raman spectrometer, which uses a green laser beam to excite the chemical bonds in a sample to produce a signal depending on what elements are bonded together, in turn providing insights into a rock's mineral composition.

"This is the first time an instrument has used Raman spectroscopy anywhere other than on Earth!" said Olivier Beyssac, CNRS research director at the Institut de Minéralogie, de Physique des Matériaux et de Cosmochimie in Paris. "Raman spectroscopy is going to play a crucial role in characterizing minerals to gain deeper insight into the geological conditions under which they formed and to detect potential organic and mineral molecules that might have been formed by living organisms."