Scientists believe that four billion years ago the two planets both had the potential to nurture life—but much of Mars' intervening history is an enigma.

Mars exploration is not to find Martian life—scientists believe nothing would survive there now—but to search for possible traces of past lifeforms.

Perseverance is tasked with searching for telltale signs that microbial life may have lived on Mars billions of years ago.

Ingredients for life

For life you need water.

A planet in what is known as the "habitable zone" around a star is an area in which water has the potential to be liquid.

If it is too close to the star the water would evaporate, too far away it would freeze (some call this the "Goldilocks principle").

But water alone is not enough.

Scientists also look for the essential chemical ingredients, including carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and sulphur.

And to stir it all up, they also look for a source of energy, said Michel Viso, an astrobiologist at CNES, the French space agency.

This could come from the Sun, if the planet is close enough, or from chemical reactions.

Martian fascination

Scientific enquiry of the red planet began in earnest in the 17th Century.

In 1609 Italian Galileo Galilei observed Mars with a primitive telescope and in doing so became the first person to use the new technology for astronomical purposes.

Mars—compared to the "desolate, empty" moon—has long seemed promising for potential inhabitability by microorganisms, wrote astrophysicist Francis Rocard in his recent essay "Latest News from Mars".

But the 20th century presented setbacks.

In the 1960s, as the race to put a man on the moon was accelerating, Dian Hitchcock and James Lovelock analysed the atmosphere on Mars looking for a chemical imbalance, gases reacting with each other, which would hint at life.

There was no reaction.

A decade later the Viking landers took atmospheric and soil samples that showed the planet was no longer inhabitable and interest in Mars crumbled.

But in 2000 scientists made a game-changing discovery: they found that water had once flowed over its surface.

This rekindled interest in Mars exploration and scientists pored over images of gullies, ravines, scouring the Martian surface for evidence of liquid water.

More than 10 years later, in 2011, they definitively found it.

Scientists now think Mars may once have been warm and wet and possibly have supported microbial life.

"As the Sun did not always have the same mass, the same energy, Mars could very well have been also in this habitable zone early in its existence," said astrophysicist Athena Coustenis, of the Paris-PSL Observatory.

If life did exist on Mars, why did it disappear?

And perhaps more profoundly if life never existed, then why not?

Further frontiers

There are always other areas to explore.

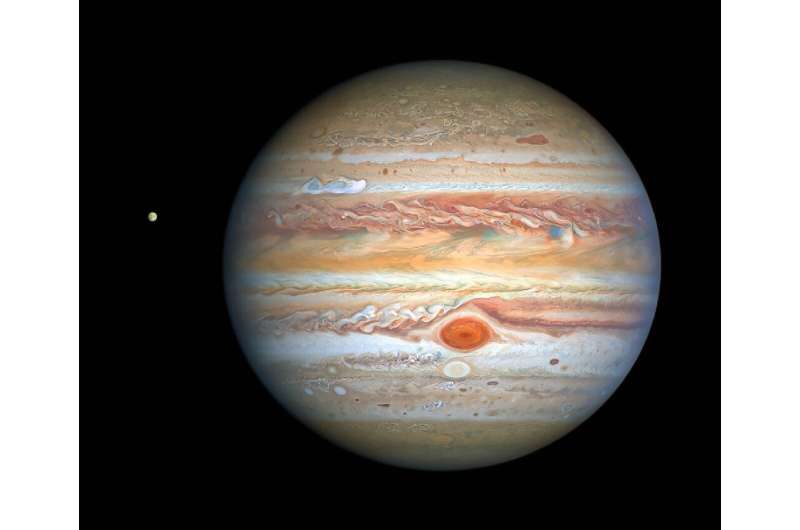

Jupiter's moon Europa, spotted by Galileo four centuries ago, may have a saltwater ocean hidden beneath its icy surface that is thought to contain about twice as much water as Earth's global ocean.

NASA says it "may be the most promising place in our solar system to find present-day environments suitable for some form of life beyond Earth".

Its tidal energy might also cause chemical reactions between water and rock on the seafloor, creating energy.

Future missions include NASA's upcoming Europa Clipper and the European probe JUICE.

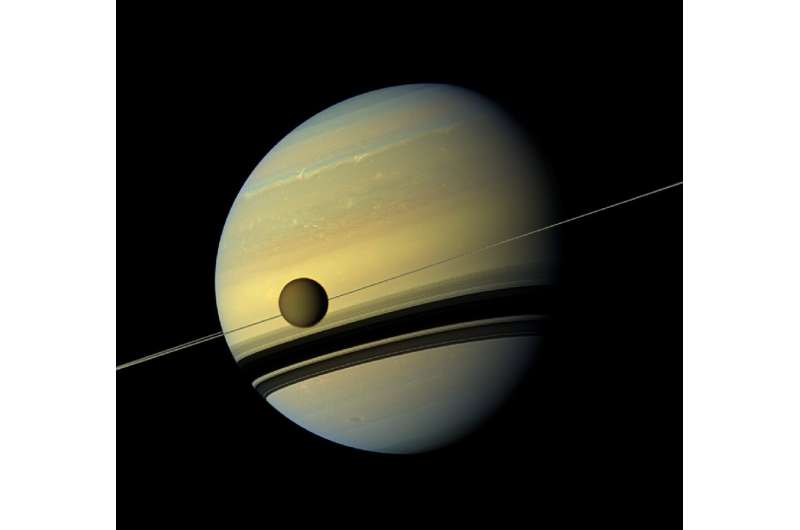

Saturn's frozen ocean moon Enceladus is also considered a promising contender.

The American Cassini probe, orbiting the planet from 2004 to 2017, discovered the existence of water vapour geysers on Enceladus.

In 2005, NASA's Cassini spacecraft discovered geysers of icy water particles and gas gushing from the moon's surface at approximately 800 miles (1,290 kilometers)per hour.

The eruptions generate fine ice dust around Enceladus, which supplies material to Saturn's ring.

No mission is currently scheduled to Enceladus.

Another of Saturn's moons Titan—the only moon in the solar system known to have a substantial atmosphere—is also of interest.

The Cassini mission found it has clouds, rain, rivers, lakes and seas, but of liquid hydrocarbons like methane and ethane.

NASA, whose Dragonfly mission will launch in 2026 and arrive in 2034, says Titan could be lifeless or harbour "life as we don't yet know it".

Explore further

© 2021 AFP