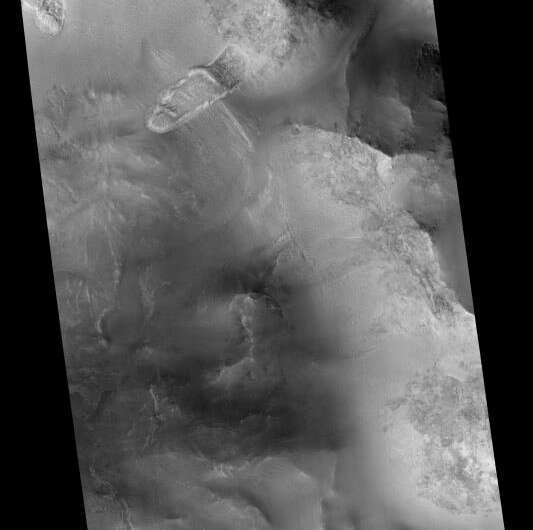

The image covers an area that measures close to 5 km across, and was taken while the MRO was 284 km above the surface. From all indications, this appears to have been the result of material in the crater wall becoming unstable.

The CTX is designed to provide large-scale background views of the terrain around smaller rock and mineral targets that are studied by other instruments on the MRO—like the High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) and the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM). It is also responsible for taking mosaic images of large areas to help with landing site selection for future missions.

Last, but not least, the CTX is responsible for monitoring locations on the Martian surface for possible changes over time. That is precisely what this image showed inside a crater wall near Nili Fossae, which experienced an infall of material since it was last photographed. The HiRISE camera also noted a similar infall of wall material on the crater's other side.

These features are the result of what geologists characterize as "mass wasting processes" (or slope processes). This term is rather broad and deals with the downhill movement of rocks and debris, including large landslides, debris avalanches, rockfalls, debris flows, and soil creep. On Mars, previous images have shown a full range of these activities, from giant rock avalanches to tiny slumps and single rockfalls.

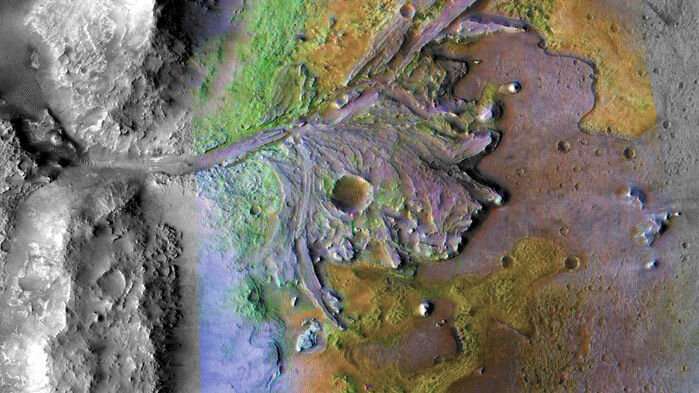

As noted, the crater captured in the CTX image lies just northwest of the Jezero Crater, which is the landing site of the Perseverance rover. This site was selected because of the delta fan located near the western wall of the crater. On Earth, these features form in the presence of moving water which slowly deposit sedimentary material over time.

Like many features in the Gale Crater, which the Curiosity rover has been studying since it landed there in 2012, this feature is evidence that Mars had flowing water on its surface billions of years ago—in the form of rivers, lakes, and even a large ocean that covered its Northern Lowlands. If life also emerged in this period, then one of the most likely places the fossilized remains would be is within delta fans.

Regardless of whether or not life once existed on Mars (or still does!) it is clear that planet is very much alive. Its geological features are a testament to both the past and present forces that actively shape it. Understanding these forces and the affect they have on the landscape are an essential part of our efforts to characterize the Martian environment (and maybe even live there someday).

Explore further