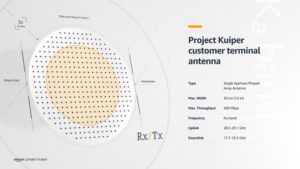

The antenna will ultimately be part of the terminals used by customers of Kuiper’s broadband services.

A key element of the design is the overlay of terminal’s transmit and receive antennas. Because transmission and reception frequencies in Ka-band are far apart from each other, the two antennas are traditionally separate, increasing the size and weight of the overall system. In Amazon’s system, the transmit and receive antennas are overlaid on top of each other in a disk about 30 centimeters across.

That’s possible, a company executive said, because of the nature of how consumer broadband works. “We were able to take advantage of some of the nuances of how people use broadband,” said David Limp, senior vice president of devices and services at Amazon, during a Dec. 16 presentation at the TC Sessions: Space conference. “There’s an inherent asymmetry of how people use broadband, in that they receive much more than they send.”

“The team was able, in a clever way, overlay Rx and Tx — receive and send — in the same lattice. By doing that, we were able to shrink down the size antenna, reuse components and bring costs down,” he said. The company also plans unspecified changes to the antennas on the satellites to enhance the performance of the consumer terminals.

Amazon has tested a prototype of the antenna, demonstrating a bandwidth of 400 megabits per second. The antenna also received 4K video streamed from a satellite in geostationary orbit. “That was a little bit of a surprise. You don’t expect your first design to hit the initial requirements, and it did,” Limp said.

A flat-panel antenna that can be produced in high volumes and relatively low costs has become one of the biggest challenges for satellite megaconstellations. Antennas with electronically steered beams are vital for seamlessly communicating with satellites as they pass in and out of view. While the technology has been demonstrated, those antennas are also expensive.

SpaceX is offering beta testers of its Starlink service a terminal that includes an antenna and router for $499. However, industry observers, including executives of rival companies, believe that antenna could cost up to four times as much to produce.

“The goal of Kuiper is to serve, eventually, we hope, tens of millions of underserved or unserved completely broadband customers,” Limp said. “To make it scale to those kinds of numbers, it has to be affordable.”

He said the new customer antenna is significantly less expensive than current “state-of-the-art” flat-panel antennas. “We set a goal of that it couldn’t be just 10 or 20 percent less expensive,” he said. “We were looking for 5 to 10 [times] decrease in cost, and we now have a path to that.”

He did not, though, offer specific targets about the cost of antenna or what Amazon will charge customers for it. “I don’t know what the end customer pricing will be. We’ll probably make that decision the day before we launch. That’s typically Amazon’s pricing strategy.”

Launch agnostic

Those antennas will communicate with a constellation of 3,236 satellites in low Earth orbit. The Federal Communications Commission authorized Project Kuiper July 30, an approval that requires Amazon to have at least half the satellites in orbit by July 2026 and the entire constellation in place by July 2029.

“We are in the middle of our design phase” for the satellite system, Limp said. That includes approaches to enable high-volume satellite production: about one satellite a day to produce all 3,236 satellites in less than nine years. “That takes reinvention of not only how you think about designing the satellite itself, but how you’re going to manufacture it.”

Amazon has yet to announce any launch contracts for Project Kuiper. A widespread industry belief is that Blue Origin has the inside track to launch those satellites, as it is owned by Jeff Bezos, chief executive of Amazon. Blue Origin executives have countered that they expect to have to compete for Project Kuiper launch contracts, as they would for any other potential customer.

Limp said that Amazon doesn’t plan to rely on Blue Origin, or any other single launch provider, for deploying its constellation. “We’re launch agnostic,” he said. “If somebody has a rocket out there, give us a call.”

He said one factor that went into Amazon’s decision to spend at least $10 billion on Project Kuiper is the changing launch market, with increased capacity and lower prices. Ten years ago, he argued, “you would not have greenlighted a project like Kuiper, because those dynamics in launch capacity, reusability, etc., make it much more viable.”

“Will I hope that Blue Origin can provide some launch capacity? Yes,” he said. “But I hope others will, too.”