Copernical Team

ESA to launch Arctic weather satellite in June

The European Space Agency said Thursday it will launch a satellite in June which will improve weather forecasting in the Arctic—a region highly exposed to the effects of global warming.

The Arctic Weather Satellite (AWS) was designed over three years by European aerospace company OHB.

The satellite, which is to be launched by a SpaceX rocket taking off from California, weighs 125 kilograms (275 pounds) and is 5.3 meters (16 feet) long with its wings deployed.

The mission is particularly important for research into global warming, said Swedish Education Minister Mats Persson.

"Mitigating climate change is a priority and space data is essential for analyzing the changes and identifying" the effective solutions," he said.

With a lifespan of approximately five years, the satellite will support others already in orbit "and provide accurate short-term weather forecasts for the Arctic region," the ESA said.

The Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the planet.

Its glaciers, forests and frozen carbon-rich soil are in danger of undergoing irreversible changes causing potential cascading repercussions across the globe.

A robot hopper to explore the moon's dangerous terrain

Intuitive Machines recently had a major breakthrough, successfully becoming the first non-governmental entity to land on the moon in February. At least the landing was partially successful—the company's Odysseus lander ended up on its side, though its instruments and communication links remained at least partially functional. That mission, dubbed IM-1, was the first in a series of ambitious missions the company has planned. And they recently released a paper at the LPSC 2024 conference detailing features of a unique hopping robot that will hitch a ride on its next moon mission.

Known as South Pole Hopper (or S.P. Hopper), the robot will be the first of a new class called µNova. Weighing in at only 35 kg and standing only 70 cm tall, this miniaturized craft is a stand-alone spacecraft that can operate entirely autonomously. It must do this to complete its mission of exploring the region around the permanently shadowed regions (PSRs) at the lunar south pole.

Which type of clouds make it harder to see the April 8 solar eclipse?

With less than a week away from the solar eclipse, weather forecasters are keeping an eye on the cloud cover, which can make or break a person's chance to see the event.

Different types of clouds have different effects on a person's viewing experience. When the moon completely covers the sun April 8, it will be the first total eclipse in North Texas since 1878.

Generally, clouds are divided based by their height: low-level, mid-level and high-level.

What are stratus clouds?

The type of clouds does depend on the system, which is the movement of warm and cold air. But in the springtime, there's a good chance the Dallas-Fort Worth area gets many stratus clouds, said Monique Sellers, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Fort Worth. They are low-level cloud layers that sometimes appear as ragged sheets, per the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Multiple layers of clouds are possible in the area, she said, but most times, lower cloud decks are observed locally. In North Texas, Sellers said, the altitude of the layers don't vary as much: lower clouds can vary anywhere from 1,500 feet to 6,000 feet in the air, mid-level clouds are anywhere between 6,500 to 23,000 feet up and high-level clouds are anything above that.

Boeing 1 month out from 4 years of catchup to SpaceX with 1st crewed Starliner flight

After nearly four years of playing catchup, Boeing is finally set to join SpaceX as one of two commercial partners capable of flying NASA astronauts to the International Space Station.

Boeing's CST-100 Starliner is aiming for a May 6 launch, carrying commander Barry "Butch" Wilmore and pilot Sunita "Suni" Williams on the Crew Flight Test. They will fly atop an Atlas V rocket from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station's Space Launch Complex 41.

The duo are looking to dock Starliner with the ISS for about eight days before bringing the spacecraft back home for a ground landing in the western U.S. It will pave the way for Boeing to begin regular service to the station as part of NASA's Commercial Crew Program, the remedy to reliance on Russia for ferry service to the ISS after the end of the space shuttle program in 2011.

"It's really exciting to finally get here to this day," said Williams, and "represent so many people who have worked for years to get this Boeing Starliner ready to go. We just happen to be the tip of the spear, the face of it, and take it to space.

Ariane 6 tests towards first flight

Video:

00:02:35

Video:

00:02:35

Europe’s next rocket, Ariane 6, passed all its qualification tests in preparation for its first flight, and the full-scale test model has been removed from the launch pad to make way for the real rocket that will ascend to space.

The test model at Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana, stood 62 m high. It is exactly the same as the ‘production model’ Ariane 6 rockets that will soon be launched, except that its boosters do not need to be tested as part of the complete rocket, so the boosters are not fuelled.

Teams preparing Ariane 6 for its

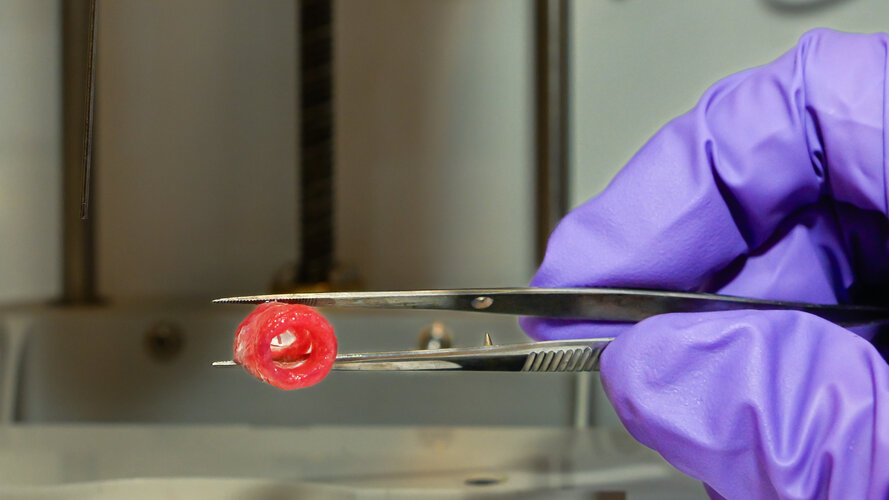

3D-bioprinted blood vessel

Image:

3D-bioprinted blood vessel

Image:

3D-bioprinted blood vessel One Tech Tip: How to use apps to track and photograph the total solar eclipse

Three companies in the running for NASA's next moon rover

Three companies are in the running to provide NASA's next moon rover for crewed missions planned later this decade, the space agency said Wednesday.

Texas-based Intuitive Machines—which landed a robot near the lunar south pole in February—Lunar Outpost of Colorado and Venturi Astrolab of California have been tasked with developing designs under a contract with a combined maximum potential value of $4.6 billion.

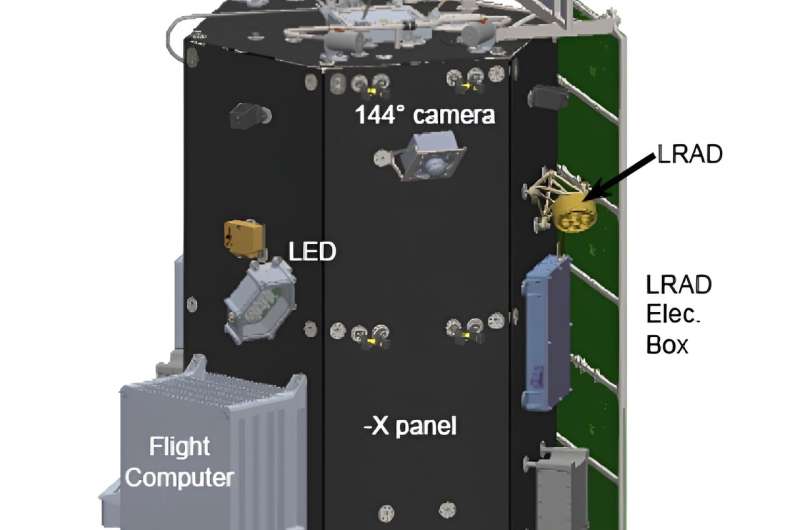

All eyes on the Arctic Weather Satellite

ESA’s new Arctic Weather Satellite has taken centre stage at OHB’s facilities in Stockholm, Sweden, before the spacecraft is packed up and shipped to California, US, for a launch currently scheduled for June.

Embracing the New Space approach to demonstrate new concepts in a cost-effective and timely manner, the Arctic Weather Satellite has been designed to show how it can improve weather forecasts in the Arctic.

AERKOMM Merges with IX Acquisition Corp in a Deal Boosting Satellite Broadband Connectivity

In a strategic move to enhance its position in the satellite technology landscape, AERKOMM Inc. (Euronext: AKOM), a frontrunner in providing broadband connectivity solutions across multiple orbits, has joined forces with IX Acquisition Corp (Nasdaq: IXAQU, "IXAQ"), a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) with a focus on the technology, media, and telecommunications sectors. This definitive

In a strategic move to enhance its position in the satellite technology landscape, AERKOMM Inc. (Euronext: AKOM), a frontrunner in providing broadband connectivity solutions across multiple orbits, has joined forces with IX Acquisition Corp (Nasdaq: IXAQU, "IXAQ"), a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) with a focus on the technology, media, and telecommunications sectors. This definitive