Copernical Team

US accuses Russia of generating orbital debris after 'destructive' satellite test, vows to respond

The United States has accused the Russian Federation of conducting a "destructive satellite test" that could put astronauts, cosmonauts, and global satellite operations at risk.

Through the U.S. State Department's spokesperson, Ned Price, it was revealed that the alleged test was conducted early Monday. Price went on to condemn the action, calling it "reckless."

The test was describe

The United States has accused the Russian Federation of conducting a "destructive satellite test" that could put astronauts, cosmonauts, and global satellite operations at risk.

Through the U.S. State Department's spokesperson, Ned Price, it was revealed that the alleged test was conducted early Monday. Price went on to condemn the action, calling it "reckless."

The test was describe US Space Force contracts Lockheed Martin for three more GPS IIIF satellites

The U.S. Space Force exercised its second contract option valued at approximately $737 million for the procurement of three additional GPS III Follow On (GPS IIIF) space vehicles (SVs) from Lockheed Martin on October 22, 2021.

This contract option is for GPS IIIF space vehicles 15, 16 and 17 (SV15-17).

GPS IIIF satellites build off the innovative design of Lockheed Martin's next gene

The U.S. Space Force exercised its second contract option valued at approximately $737 million for the procurement of three additional GPS III Follow On (GPS IIIF) space vehicles (SVs) from Lockheed Martin on October 22, 2021.

This contract option is for GPS IIIF space vehicles 15, 16 and 17 (SV15-17).

GPS IIIF satellites build off the innovative design of Lockheed Martin's next gene US calls Russian anti-satellite missile test reckless, irresponsible

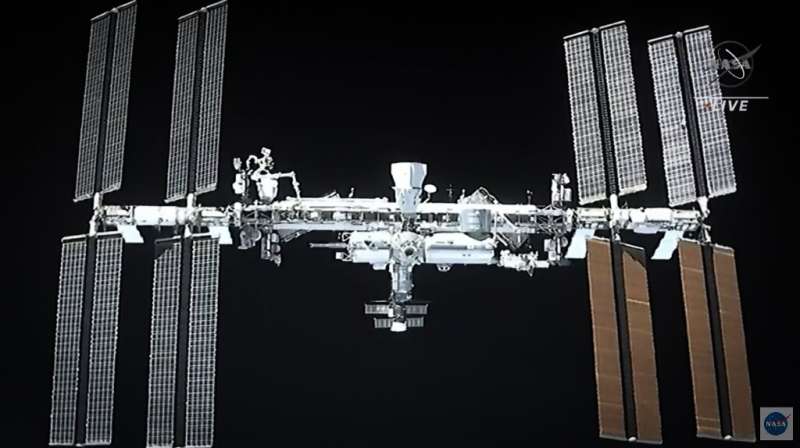

The United States on Monday called a Russian anti-satellite missile test "reckless" and "irresponsible" after debris from the test endangered astronauts working aboard the International Space Station.

The seven astronauts were forced to take shelter in their space capsules as a cloud of space junk moved toward the station at high speeds.

While the debris eventually moved away from th

The United States on Monday called a Russian anti-satellite missile test "reckless" and "irresponsible" after debris from the test endangered astronauts working aboard the International Space Station.

The seven astronauts were forced to take shelter in their space capsules as a cloud of space junk moved toward the station at high speeds.

While the debris eventually moved away from th Russia says S-550 more efficient at intercepting ICBMs than THAAD and Aegis

The new air defence system is being developed on the basis of the advanced S-500 Prometey (Prometheus), designed to destroy enemy targets within a range of around 600 kilometres (370 miles).

Russia's S-550 will become the world's first mobile special operation missile and airspace defence system capable of effectively destroying intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM), two sources in th

The new air defence system is being developed on the basis of the advanced S-500 Prometey (Prometheus), designed to destroy enemy targets within a range of around 600 kilometres (370 miles).

Russia's S-550 will become the world's first mobile special operation missile and airspace defence system capable of effectively destroying intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM), two sources in th AFRL awards $1b contract to Space Dynamics Laboratory

The Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) has awarded its largest-ever contract for space-related technology development and mission support.

The contract, worth up to $1B, was awarded to Utah State University Space Dynamics Laboratory (USU/SDL) a University Affiliated Research Center (UARC) to ensure an essential engineering, research, and development capability, provided by an educational

The Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) has awarded its largest-ever contract for space-related technology development and mission support.

The contract, worth up to $1B, was awarded to Utah State University Space Dynamics Laboratory (USU/SDL) a University Affiliated Research Center (UARC) to ensure an essential engineering, research, and development capability, provided by an educational NASA Invites Media to Webb Telescope Science Briefings

NASA will hold two virtual media briefings Thursday, Nov. 18, on the science goals and capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope.

NASA will hold two virtual media briefings Thursday, Nov. 18, on the science goals and capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope. The longest lunar eclipse in centuries will happen this week, NASA says

You can see the longest partial lunar eclipse in hundreds of years this week.

The "nearly total" lunar eclipse is expected overnight Thursday, Nov. 18, to Friday, Nov. 19, NASA said.

"The Moon will be so close to opposite the Sun on Nov 19 that it will pass through the southern part of the shadow of the Earth for a nearly total lunar eclipse," NASA said on its website.

The eclipse will last 3 hours, 28 minutes and 23 seconds, making it the longest in centuries, Space.com reported.

Only a small sliver of the moon will be visible during the eclipse. About 97% of the moon will disappear into Earth's shadow as the sun and moon pass opposite sides of the planet, EarthSky reported.

The moon should appear to be a reddish-brown color as it slips into the shadow, NASA reported.

The eclipse will be visible in many parts of the world, including North America, eastern Australia, New Zealand and Japan, according to EarthSky.

"For U.S. East Coast observers, the partial eclipse begins a little after 2 a.m.

Russia satellite destruction put ISS at greater risk: ESA official

Russia's destruction of one of its own satellites generated a cloud of debris near the International Space Station (ISS) and its seven-strong crew.

For Didier Schmitt, a senior figure at the European Space Agency (ESA), Moscow's action increased the risk of a collision in space.

Question: Was this a close call for the seven astronauts—four US, two Russians and a German - aboard the ISS?

Answer: "It's difficult to say with hindsight. But what we know is that from now on, according to our sources, the risk of collision could be five times greater in the weeks, even the months ahead.

"The new debris is moving in the same orbit as the Station, which is to around 400 kilometres in altitude, at more than 8 kilometres a second. That's seven to eight times faster than a rifle bullet! So to avoid them you have to predict a long time in advance: you can raise or lower the ISS a little.

NASA TV to Air DART Prelaunch Activities, Launch

NASA will provide coverage of the upcoming prelaunch and launch activities for the agency’s first planetary defense test mission, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART).

NASA will provide coverage of the upcoming prelaunch and launch activities for the agency’s first planetary defense test mission, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART). Germany calls for space security rules; Russia dismisses any danger to ISS crew

Germany's government said Tuesday it was "very concerned" by Russia's destruction of one of its own satellites during a missile test, calling for urgent measures to "strengthen security and confidence".

"We call on all states to engage constructively in this process and in the development of principles for responsible behaviour in space," the Germany foreign ministry said in a statement.

Germany's government said Tuesday it was "very concerned" by Russia's destruction of one of its own satellites during a missile test, calling for urgent measures to "strengthen security and confidence".

"We call on all states to engage constructively in this process and in the development of principles for responsible behaviour in space," the Germany foreign ministry said in a statement.