Copernical Team

Perseverance starts Jezero Delta campaign

We made it! Perseverance is at the delta, and gracing us with stunning images to pour over. Mars 2020 is officially out of "Rapid Traverse" mode, where we put the pedal to the metal and focused on driving. This week, we are back to standard operations, and the team is beginning our Delta Front Campaign. You can check out last week's blog for details on why exploring the delta is so exciting.

We made it! Perseverance is at the delta, and gracing us with stunning images to pour over. Mars 2020 is officially out of "Rapid Traverse" mode, where we put the pedal to the metal and focused on driving. This week, we are back to standard operations, and the team is beginning our Delta Front Campaign. You can check out last week's blog for details on why exploring the delta is so exciting. NASA, partners develop 'lunar backpack' technology to aid moon explorers

Imagine a mountaineering expedition in a wholly uncharted environment, where the hikers had the ability to generate a real-time 3D map of the terrain. NASA researchers and their industry partners have developed a remote-sensing mapping system set to aid explorers in the most isolated wilderness imaginable: the airless wastes at the South Pole of the Moon.

The Kinematic Navigation and Carto

Imagine a mountaineering expedition in a wholly uncharted environment, where the hikers had the ability to generate a real-time 3D map of the terrain. NASA researchers and their industry partners have developed a remote-sensing mapping system set to aid explorers in the most isolated wilderness imaginable: the airless wastes at the South Pole of the Moon.

The Kinematic Navigation and Carto Lucy is "Go" for solar array deployment attempt

On April 18, NASA decided to move forward with plans to complete the deployment of the Lucy spacecraft's stalled, unlatched solar array. The spacecraft is powered by two large arrays of solar cells that were designed to unfold and latch into place after launch. One of the fan-like arrays opened as planned, but the other stopped just short of completing this operation.

Through a combination

On April 18, NASA decided to move forward with plans to complete the deployment of the Lucy spacecraft's stalled, unlatched solar array. The spacecraft is powered by two large arrays of solar cells that were designed to unfold and latch into place after launch. One of the fan-like arrays opened as planned, but the other stopped just short of completing this operation.

Through a combination A roadmap for deepening understanding of a puzzling universal process

A puzzling process called magnetic reconnection triggers explosive phenomena throughout the universe, creating solar flares and space storms that can take down mobile phone service and electrical power grids. Now scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) have detailed a roadmap for untangling a key aspect of this puzzle that could deepen insig

A puzzling process called magnetic reconnection triggers explosive phenomena throughout the universe, creating solar flares and space storms that can take down mobile phone service and electrical power grids. Now scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) have detailed a roadmap for untangling a key aspect of this puzzle that could deepen insig Beaming solar power from satellite array is Earth Day focus for AFRL

In honor of Earth Day, the Air Force Research Laboratory, or AFRL, is highlighting its efforts toward harnessing the Sun's energy, converting it to radio frequency, or RF, and beaming it to the Earth providing a green power source for the U.S. and allied forces.

Key technologies need to be developed to make such a challenging process a reality.

In response to this challenge, AFRL for

In honor of Earth Day, the Air Force Research Laboratory, or AFRL, is highlighting its efforts toward harnessing the Sun's energy, converting it to radio frequency, or RF, and beaming it to the Earth providing a green power source for the U.S. and allied forces.

Key technologies need to be developed to make such a challenging process a reality.

In response to this challenge, AFRL for ESA’s satnav summer school open to students

This year’s ESA/JRC International Summer School on Global Navigation Satellite Systems will take place in July, at Kraków in the South of Poland.

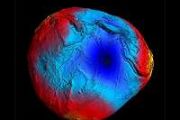

Week in images: 18-22 April 2022

Week in images: 18-22 April 2022

Discover our week through the lens

Black holes raze thousands of stars to fuel growth

In some of the most crowded parts of the universe, black holes may be tearing apart thousands of stars and using their remains to pack on weight. This discovery, made with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, could help answer key questions about an elusive class of black holes.

While astronomers have previously found many examples of black holes tearing stars apart, little evidence has been

In some of the most crowded parts of the universe, black holes may be tearing apart thousands of stars and using their remains to pack on weight. This discovery, made with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, could help answer key questions about an elusive class of black holes.

While astronomers have previously found many examples of black holes tearing stars apart, little evidence has been Space dust, asteroids and comets can account for all water on Mercury

Mercury harbors water ice in the shadows of the steepest craters around its poles. But it is unclear how those water molecules ended up on Mercury. Now a new simulation shows that incoming minor bodies such as asteroids, comets and dust particles carry enough water to account for all the ice sheets present. The study could form the basis for new research on water in exoplanetary systems. Publica

Mercury harbors water ice in the shadows of the steepest craters around its poles. But it is unclear how those water molecules ended up on Mercury. Now a new simulation shows that incoming minor bodies such as asteroids, comets and dust particles carry enough water to account for all the ice sheets present. The study could form the basis for new research on water in exoplanetary systems. Publica Planet joins ESA Third Party Mission Program for satellite imagery

Planet Labs PBC (NYSE: PL), a leading provider of daily data and insights about Earth, has announced that Planet's PlanetScope and SkySat data have joined the European Space Agency (ESA) Third Party Missions portfolio, enabling ESA to utilize Planet data for scientific, research, and pre-operational Earth Observation based applications development. Through distribution under the ESA Earthnet Pro

Planet Labs PBC (NYSE: PL), a leading provider of daily data and insights about Earth, has announced that Planet's PlanetScope and SkySat data have joined the European Space Agency (ESA) Third Party Missions portfolio, enabling ESA to utilize Planet data for scientific, research, and pre-operational Earth Observation based applications development. Through distribution under the ESA Earthnet Pro