Copernical Team

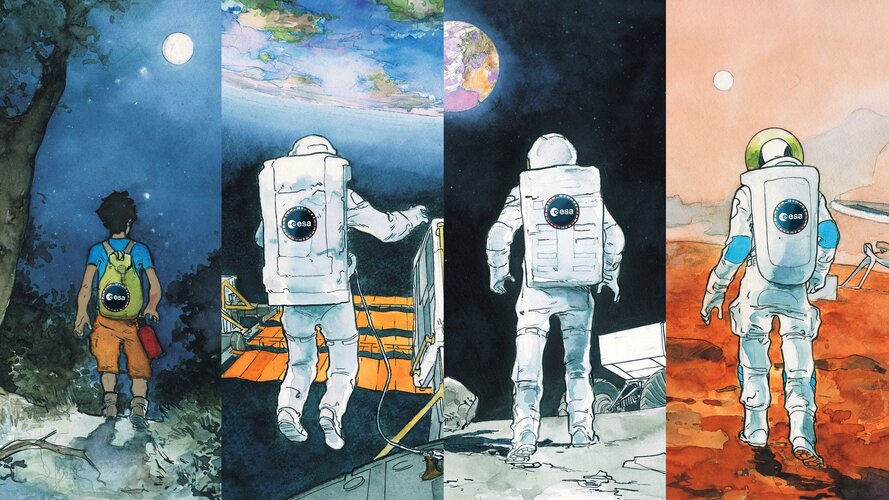

From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars: ESA’s exploration roadmap for space autonomy and leadership

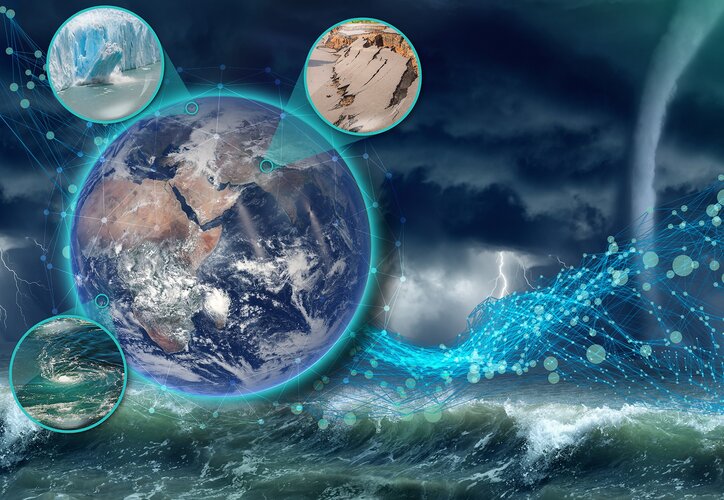

Watch: Earth Explorer 10 Consultation

Watch: Earth Explorer 10 Consultation

On 5 July, follow the discussion on Harmony at the User Consultation Meeting for ESA's tenth Earth Explorer

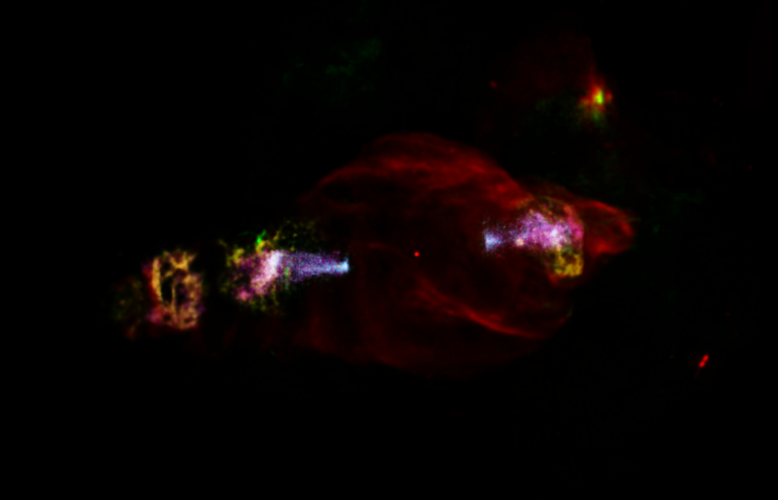

Cosmic manatee accelerates particles from head

Image:

Cosmic manatee accelerates particles from head

Image:

Cosmic manatee accelerates particles from head What Are The Top 3 Celestial Events In 2022

Before we excite you with the 3 major celestial events scheduled to occur in 2022, let's figure out what celestial events are. These pertain to an astronomical field of interest that involves all celestial objects, including objects relating to visible heavens or the sky, such as the moon, sun, and stars.

Before we excite you with the 3 major celestial events scheduled to occur in 2022, let's figure out what celestial events are. These pertain to an astronomical field of interest that involves all celestial objects, including objects relating to visible heavens or the sky, such as the moon, sun, and stars. Seismic waves from earthquakes reveal changes in the Earth's outer core

In May 1997, a large earthquake shook the Kermadec Islands region in the South Pacific Ocean. A little over 20 years later, in September 2018, a second big earthquake hit the same location, its waves of seismic energy emanating from the same region.

Though the earthquakes occurred two decades apart, because they occurred in the same region, they'd be expected to send seismic waves through

In May 1997, a large earthquake shook the Kermadec Islands region in the South Pacific Ocean. A little over 20 years later, in September 2018, a second big earthquake hit the same location, its waves of seismic energy emanating from the same region.

Though the earthquakes occurred two decades apart, because they occurred in the same region, they'd be expected to send seismic waves through Iceland volcano eruption opens a rare window into the Earth beneath our feet

The recent Fagradalsfjall eruption in the southwest of Iceland has enthralled the whole world, including nature lovers and scientists alike. The eruption was especially important as it provided geologists with a unique opportunity to study magmas that were accumulated in a deep crustal magma reservoir but ultimately derived from the Earth's mantle (below 20 km).

A research team from Univer

The recent Fagradalsfjall eruption in the southwest of Iceland has enthralled the whole world, including nature lovers and scientists alike. The eruption was especially important as it provided geologists with a unique opportunity to study magmas that were accumulated in a deep crustal magma reservoir but ultimately derived from the Earth's mantle (below 20 km).

A research team from Univer Processing photons in picoseconds

Light has long been used to transmit information in many of our everyday electronic devices. Because light is made of quantum particles called photons, it will also play an important role in information processing in the coming generation of quantum devices. But first, researchers need to gain control of individual photons. Writing in Optica, Columbia Engineers propose using a time lens.

"

Light has long been used to transmit information in many of our everyday electronic devices. Because light is made of quantum particles called photons, it will also play an important role in information processing in the coming generation of quantum devices. But first, researchers need to gain control of individual photons. Writing in Optica, Columbia Engineers propose using a time lens.

" Physicists confront the neutron lifetime puzzle

To solve a long-standing puzzle about how long a neutron can "live" outside an atomic nucleus, physicists entertained a wild but testable theory positing the existence of a right-handed version of our left-handed universe. They designed a mind-bending experiment at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory to try to detect a particle that has been speculated but not spotted. If fo

To solve a long-standing puzzle about how long a neutron can "live" outside an atomic nucleus, physicists entertained a wild but testable theory positing the existence of a right-handed version of our left-handed universe. They designed a mind-bending experiment at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory to try to detect a particle that has been speculated but not spotted. If fo Floating in space might be fun, but TBone study shows it's hard on earthly bodies

Ever wondered if you have anything in common with an astronaut? Turns out there are 206 things - your bones. It's these parts of our body that are the focus of a research study on bone loss in astronauts, and the important question of whether bone can be re-gained after returning to Earth.

The TBone study was started in 2015 by Dr. Steven Boyd, PhD, director of the McCaig Institute for Bon

Ever wondered if you have anything in common with an astronaut? Turns out there are 206 things - your bones. It's these parts of our body that are the focus of a research study on bone loss in astronauts, and the important question of whether bone can be re-gained after returning to Earth.

The TBone study was started in 2015 by Dr. Steven Boyd, PhD, director of the McCaig Institute for Bon Virgin Orbit rocket launches 7 US defense satellites

A Virgin Orbit rocket carrying seven U.S. Defense Department satellites was launched from a special Boeing 747 flying off the Southern California coast and streaked toward space Friday night.

The modified jumbo jet took off from Mojave Air and Space Port in the Mojave Desert and released the rocket over the Pacific Ocean, northwest of Los Angeles.

The launch was procured by the U.S. Space Force for a Defense Department test program. The seven payloads will conduct various experiments.

"And there we have it, folks!" the company tweeted shortly before 1 a.m. local time, about an hour after the rocket separated from the 747. "NewtonFour successfully reignited and deployed all customer spacecraft into their target orbit."

It was Virgin Orbit's fourth commercial launch and first night launch. The launch was originally scheduled for Wednesday night, but that attempt was scrubbed due to a propellant temperature issue.

Virgin Orbit named the mission "Straight Up" after the hit on Paula Abdul's debut studio album "Forever Your Girl," which was released through Virgin Records in 1988.

Virgin Orbit was founded in 2017 by British billionaire Richard Branson.