Copernical Team

Smaller, stronger magnets could improve fusion devices

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) have found a way to build powerful magnets smaller than before, aiding the design and construction of machines that could help the world harness the power of the sun to create electricity without producing greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change.

The scientists found a way to build hi

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) have found a way to build powerful magnets smaller than before, aiding the design and construction of machines that could help the world harness the power of the sun to create electricity without producing greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change.

The scientists found a way to build hi Satellite operators Eutelsat, OneWeb agree to merge

French and British satellite operators Eutelsat and OneWeb announced Tuesday plans to merge and create a "global champion" in broadband internet, rivalling US giants such as Elon Musk's Starlink.

Eutelsat and OneWeb said in a joint statement that they have signed a memorandum of understanding to join forces to become "a leading global player in connectivity... in an all-share transaction."

French and British satellite operators Eutelsat and OneWeb announced Tuesday plans to merge and create a "global champion" in broadband internet, rivalling US giants such as Elon Musk's Starlink.

Eutelsat and OneWeb said in a joint statement that they have signed a memorandum of understanding to join forces to become "a leading global player in connectivity... in an all-share transaction." Making Muons for Scientific Discovery, National Security

The Defense Department and other federal agencies have sought advanced sources that generate gamma rays, X-rays, neutrons, protons, and electrons to enable a variety of scientific, commercial, and defense applications - from medical diagnostics, to scans of cargo containers for dangerous materials, to non-destructive testing of aircraft and their parts to see internal defects. But none of these

The Defense Department and other federal agencies have sought advanced sources that generate gamma rays, X-rays, neutrons, protons, and electrons to enable a variety of scientific, commercial, and defense applications - from medical diagnostics, to scans of cargo containers for dangerous materials, to non-destructive testing of aircraft and their parts to see internal defects. But none of these UCLA scientists discover places on the moon where it's always 'sweater weather'

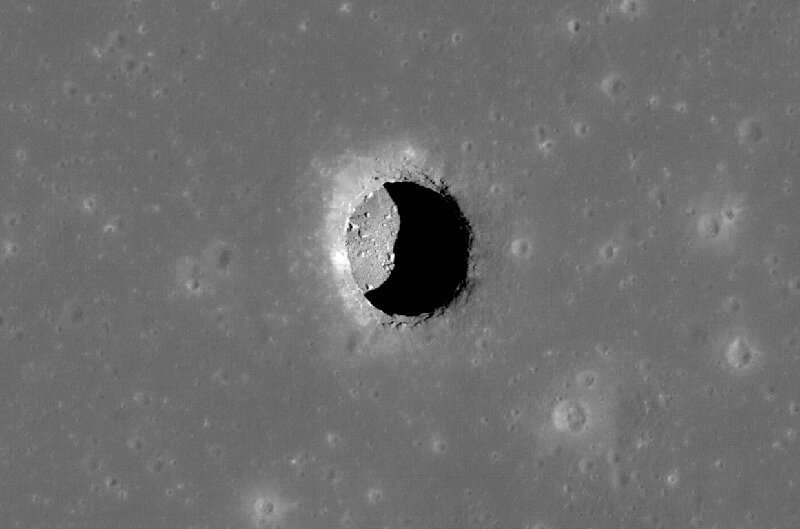

Future human explorers on the moon might have 99 problems but staying warm or cool won't be one. A team led by planetary scientists at UCLA has discovered shady locations within pits on the moon that always hover around a comfortable 63 degrees Fahrenheit.

The pits, and caves to which they may lead, would make safer, more thermally stable base camps for lunar exploration and long-term habi

Future human explorers on the moon might have 99 problems but staying warm or cool won't be one. A team led by planetary scientists at UCLA has discovered shady locations within pits on the moon that always hover around a comfortable 63 degrees Fahrenheit.

The pits, and caves to which they may lead, would make safer, more thermally stable base camps for lunar exploration and long-term habi EarthCARE taking wing

Image:

EarthCARE taking wing

Image:

EarthCARE taking wing Buzz Aldrin's Apollo 11 jacket sold for $2.7 mn

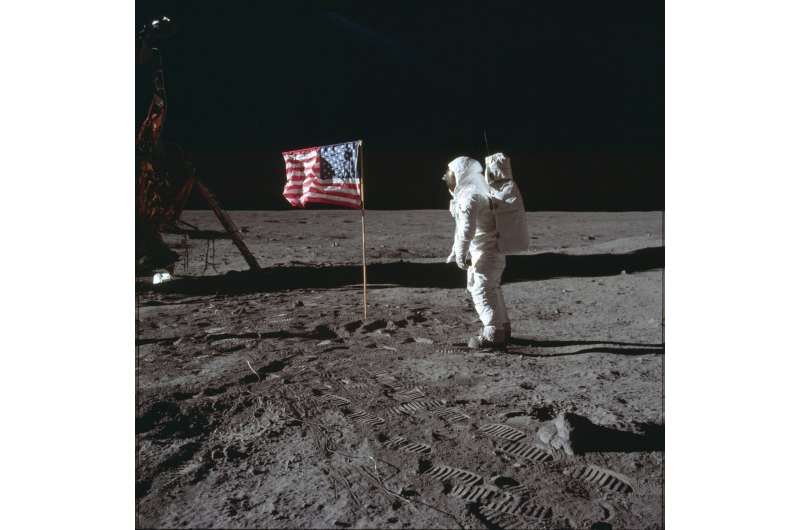

The jacket worn by US astronaut Buzz Aldrin during his 1969 flight to the Moon aboard Apollo 11 was sold at auction for $2.7 million in New York Tuesday, Sotheby's announced.

The white jacket, adorned with an American flag, NASA's initials, a patch for the Apollo 11 mission and the name "E. ALDRIN," is part of a personal collection of items the 92-year-old astronaut decided to put up for sal

The jacket worn by US astronaut Buzz Aldrin during his 1969 flight to the Moon aboard Apollo 11 was sold at auction for $2.7 million in New York Tuesday, Sotheby's announced.

The white jacket, adorned with an American flag, NASA's initials, a patch for the Apollo 11 mission and the name "E. ALDRIN," is part of a personal collection of items the 92-year-old astronaut decided to put up for sal Bidder pays $2.8M for jacket worn in space by Buzz Aldrin

US regrets 'surprise' Russia exit from Space Station

The United States on Tuesday voiced regret over Russia's announcement that it would exit the International Space Station after 2024 and said it was taken by surprise.

"It's an unfortunate development given the critical scientific work performed at the ISS, the valuable professional collaboration our space agencies have had over the years, and especially in light of our renewed agreement on space-flight cooperation," State Department spokesman Ned Price said.

"I understand that we were taken by surprise by the public statement," he told reporters.

NASA's director of the ISS, Robyn Gatens, earlier said that the US space agency had not "received any official word from the partner as to the news today."

NASA itself plans to retire the ISS—a symbol of post-Cold War unity—after 2030 as it transitions to working with commercial space stations, and Gatens suggested Russia might be thinking about its own transition.

Asked whether she wanted the US-Russia space relationship to end, she replied: "No, absolutely not."

"They have been good partners, as all of our partners are, and we want to continue together, as a partnership, to continue operating space station through the decade.

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter finds lunar pits harbor comfortable temperatures

NASA-funded scientists have discovered shaded locations within pits on the Moon that always hover around a comfortable 63 F (about 17 C) using data from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) spacecraft and computer modeling.

The pits, and caves to which they may lead, would make thermally stable sites for lunar exploration compared to areas at the Moon's surface, which heat up to 260 F (about 127 C) during the day and cool to minus 280 F (about minus 173 C) at night.

Microchips headed to space on NASA's Artemis I moon mission

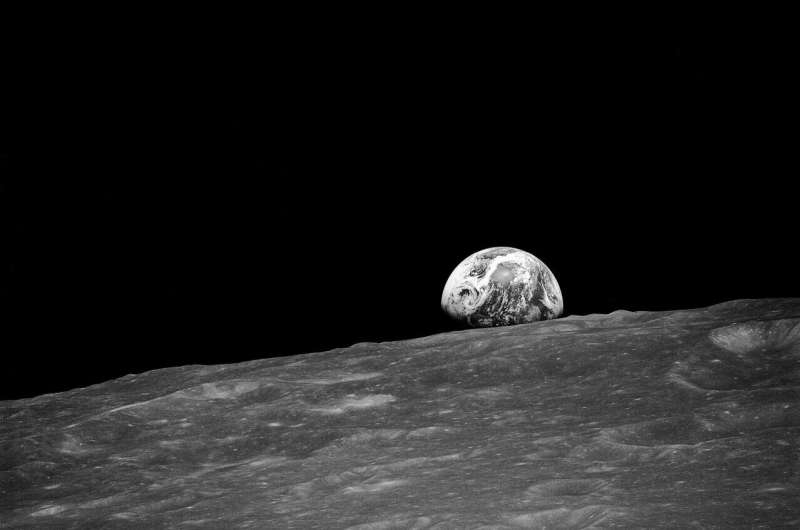

On July 20, 53 years after Neil Armstrong took one small step for man and one giant leap for mankind, NASA announced target launch dates for the Artemis I mission, the agency's long-awaited first step to returning astronauts to the moon and eventually Mars. Even though there won't be people onboard the Orion spacecraft when it blasts off later this summer, it will carry dozens of tiny tributes to the Artemis team that were created at the University of Houston.

Long Chang, a research associate professor in the Cullen College of Engineering and expert at the UH nanofabrication facility, answered the call when NASA was looking for a way to honor the thousands of people who contributed to the Artemis I mission.

"NASA wanted microchips with everyone's name on them," said Long. "But I had some creative liberties in the design because they didn't really know what we were capable of."

After considering several options that would satisfy NASA's requirements, Long proposed a process that combines electron beam lithography and reactive ion etching to engrave the nearly 30,000 names onto each of the 80 microchips.