Copernical Team

NOAA satellite, NASA LOFTID heat shield experiment launched into orbit

The third of five advanced NOAA satellites launched into orbit early Thursday from California's Vandenberg Space Force Base. The Joint Polar Satellite System-2 will provide a continuous stream of vital weather data.

"The need for advanced satellites, such as JPSS-2, to accurately predict weather and climate has never been greater," said Michael C. Morgan, assistant secretary of commerce

The third of five advanced NOAA satellites launched into orbit early Thursday from California's Vandenberg Space Force Base. The Joint Polar Satellite System-2 will provide a continuous stream of vital weather data.

"The need for advanced satellites, such as JPSS-2, to accurately predict weather and climate has never been greater," said Michael C. Morgan, assistant secretary of commerce Airbus and Space Compass to target Japanese market for mobile and EO solutions

Airbus HAPS Connectivity Business (Airbus HAPS) has signed a Letter of Intent (LOI) with Space Compass Corporation of Japan (Space Compass) for a cooperation agreement to service the Japanese market with mobile connectivity and earth observation services from the Stratosphere with Airbus' record breaking Zephyr platform.

Samer Halawi, Chief Executive of Airbus HAPS, commented on the agreem

Airbus HAPS Connectivity Business (Airbus HAPS) has signed a Letter of Intent (LOI) with Space Compass Corporation of Japan (Space Compass) for a cooperation agreement to service the Japanese market with mobile connectivity and earth observation services from the Stratosphere with Airbus' record breaking Zephyr platform.

Samer Halawi, Chief Executive of Airbus HAPS, commented on the agreem Kanyini CubeSat coming together in Adelaide

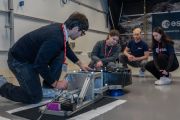

With its 2023 launch announced by the South Australian government, here's a look inside the Kanyini CubeSat.

It's the multi-million-dollar satellite that will collect invaluable data from space once it takes off into the cosmos.

But the pieces of the puzzle that make up the $6.5 million CubeSat mission, dubbed Kanyini, have been scattered across labs and workshops across South Austra

With its 2023 launch announced by the South Australian government, here's a look inside the Kanyini CubeSat.

It's the multi-million-dollar satellite that will collect invaluable data from space once it takes off into the cosmos.

But the pieces of the puzzle that make up the $6.5 million CubeSat mission, dubbed Kanyini, have been scattered across labs and workshops across South Austra Hurricane causes only minor damage to Artemis rocket

After initial visual inspections, NASA said on Thursday that its new mega moon rocket apparently suffered no major damage after Hurricane Nicole hit Florida.

But employees must conduct further checks on site as soon as possible to confirm the initial assessment, said Jim Free, associate administrator at the US space agency.

Free said that NASA teams employing cameras at the launch pad at

After initial visual inspections, NASA said on Thursday that its new mega moon rocket apparently suffered no major damage after Hurricane Nicole hit Florida.

But employees must conduct further checks on site as soon as possible to confirm the initial assessment, said Jim Free, associate administrator at the US space agency.

Free said that NASA teams employing cameras at the launch pad at NASA views images, confirms discovery of Shuttle Challenger artifact

NASA leaders recently viewed footage of an underwater dive off the East coast of Florida, and they confirm it depicts an artifact from the space shuttle Challenger.

The artifact was discovered by a TV documentary crew seeking the wreckage of a World War II-era aircraft. Divers noticed a large humanmade object covered partially by sand on the seafloor. The proximity to the Florida Space Coa

NASA leaders recently viewed footage of an underwater dive off the East coast of Florida, and they confirm it depicts an artifact from the space shuttle Challenger.

The artifact was discovered by a TV documentary crew seeking the wreckage of a World War II-era aircraft. Divers noticed a large humanmade object covered partially by sand on the seafloor. The proximity to the Florida Space Coa ULA launches weather satellite for NOAA and Re-entry test for NASA

United Launch Alliance has successfully launched the third in a series of polar-orbiting weather satellites for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) at 1:49 a.m. PST Thursday, as well as a NASA technology demonstration misison on a ULA Atlas V rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California.

Mission managers for NOAA's JPSS-2 confirm the satellite is now in Sun

United Launch Alliance has successfully launched the third in a series of polar-orbiting weather satellites for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) at 1:49 a.m. PST Thursday, as well as a NASA technology demonstration misison on a ULA Atlas V rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California.

Mission managers for NOAA's JPSS-2 confirm the satellite is now in Sun Earth from Space: Santiago, Chile

The Copernicus Sentinel-2 mission captured this image of Santiago – the capital and largest city of Chile.

Cosmic radiation detection takes front seat during NASA's Artemis I space mission

Although bad weather and technical issues forced NASA to postpone its August and September launch attempts for Artemis I—an uncrewed space mission that will voyage around the moon and back—the space agency is looking towards a launch window in the second half of November 2022, possibly November 16. The highly anticipated space flight will be the first to test the new Orion spacecraft along with its rocket and ground systems.

The Artemis I mission is the first step in NASA's plans to carry human crews to further explore the lunar surface and eventually establish a sustainable outpost on the moon. The flight would also contribute to the groundwork required for a mission to Mars. When it blasts off from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, Artemis I will carry two mannequins strapped into its crew module.

Section of destroyed shuttle Challenger found on ocean floor

US weather satellite, test payload launched into space

A satellite intended to improve weather forecasting and an experimental inflatable heat shield to protect spacecraft entering atmospheres were launched into space from California on Thursday.

A United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket carrying the Joint Polar Satellite System-2 satellite and the NASA test payload lifted off at 1:49 a.m. from Vandenberg Space Force Base, northwest of Los Angeles.

Developed for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, JPSS-2 was placed into an orbit that circles the Earth from pole to pole, joining previously launched satellites in a system designed to improve weather forecasting and climate monitoring.

The NASA mission blog said there was no immediate data confirming deployment of the solar array that will power the satellite. "There may not be an issue, but we're monitoring closely as more telemetry data becomes available," the post said.

The array has five panels that were collapsed in an accordion fold for launch. The fully deployed array would extend 30 feet (9.1 meters).

Mission officials say the satellite represents the latest technology and will increase precision of observations of the atmosphere, oceans and land.

After releasing the satellite, the rocket's upper stage reignited to position the test payload for re-entry into Earth's atmosphere and descent into the Pacific Ocean.